The Bolter (3 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Idina dreamt of that better life. Whenever she reinvented her life with a new husband, she believed that, this time round, she could make it happen. Yet that better life remained frustratingly just out of reach. Eventually she found the courage to stop and look back. But, by then, it was too late.

When she died, openly professing, “I should never have left Euan,”

29

she had a photograph of him beside her bed. Thirty years after that first divorce she had just asked that one of her grandsons—through another marriage—bear his name. Her daughter, the boy’s mother, who had never met the ex-husband her mother was talking about, obliged.

At the end of her life, Idina had clearly continued to love Euan Wallace deeply. Yet she had left him. Why?

The question would not leave me.

˙ ˙ ˙

MY MOTHER TOLD ME

almost none of the above. In fact, she told me barely anything at all. She simply said that Idina’s first marriage had been to her grandfather, Euan Wallace, and that Euan Wallace was, by all accounts, breathtakingly handsome, heartbreakingly kind, and as rich as Croesus. Their first child, David, had been my mother’s father. A year later Euan and Idina had had another son, Gee. Idina had then gone to Africa, leaving the two boys. Euan married the famously beautiful eldest daughter of the architect Sir Edwin Lutyens and had three more sons. Later, within three years during the Second World War, Euan Wallace and four of his five sons, including my mother’s father, had all died. My mother had been two years old, and had no memory of her father. None of the other sons had any children, including Billy, who was the only one to survive the war but died of cancer before the age of fifty. My mother had barely crossed paths with him, she said. The Wallace family had come to an abrupt end.

After this much, my mother raised a wall of noisy silence.

Idina was not, she said, a person to admire.

IN 1990, WHEN I WAS TWENTY-ONE

, Billy Wallace’s widow, Liz, died and we received a pile of photograph albums and some cardboard boxes. I sat on the floor of my parents’ London sitting room and ferreted through them with my mother. The albums fell open to reveal endless pictures of Billy and his mother, Barbie, picnicking with the Royal Family; the princesses Elizabeth and Margaret as children outside Barbie’s house; and a large black-and-white photograph of a young and beautiful Princess Margaret in the passenger seat of an open-topped car, Billy behind the wheel.

My eyes widened.

“Aah, is this why your paths didn’t cross?”

My mother nodded. “Different lives,” she added. “Now I need your help with this.”

She lifted the lid off one of the cardboard boxes and scattered the contents on the floor. In front of me lay the photographs of five young Second World War officers. Their hair was slicked down under their caps, their skin unblemished, noses and cheekbones shining. The portraits were unnamed.

“There must,” my mother continued, “be some way of working it out.”

She could identify her father from the other photographs she had. She had also known Billy well enough to pick him out. The three who remained were all RAF pilots: bright-eyed, smiling pinup boys in their uniforms. They were my mother’s uncles, Johnny, Peter, and Gee Wallace. Yet we didn’t know who was who. Each one of them had died shortly afterward, and this was all of their brief lives that survived. Apart from my mother and her sister, who had been toddlers when they had died, the only relative left to ask was my mother’s mother. And, even fifty years on, these deaths still upset her almost too deeply to raise the matter. After a couple of hours of puzzling, we slipped the pictures back into the mass grave of the box.

“I was only two when my father went,” my mother murmured.

“Not went, died. Nobody left you. They all simply died, one by one.”

There was a theory, my mother continued, that it was the pink house. Pink houses are unlucky. They moved into that pink house and then they all went.

I nodded. My mother was not having a logical moment. The best thing to do was to nod.

Then, softly, I broke in. “Idina didn’t die then, though. Did you ever meet her, Mum?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Why not?”

“Well, it would have been disloyal to Barbie, who brought up my father. In any case, Idina wasn’t interested in my sister and me. She didn’t care.”

“Oh.”

“She was not a nice woman.”

“Why, Mum? You’re not that old-fashioned. Just having a few lovers doesn’t make you a bad person.”

“Well, it’s not exactly the best, or happiest, way to behave, but you’re right, that didn’t make her a bad person.”

“Then what did?”

My mother turned and looked me straight in the eye. “My grandmother was a selfish woman, Frances. In 1918, when my father was four and his younger brother, Gerard, just three, she walked out on them and her devoted husband and disappeared to live in Kenya with someone else.”

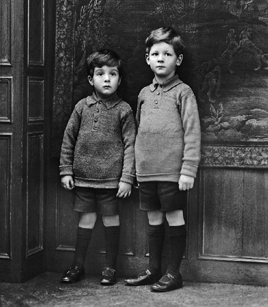

Then she went upstairs and came down again with another photograph. It was a black-and-white picture of two tiny boys in thick woolen and collared jerseys and knee-length shorts. Their hair has been tidied

for the photograph but on each it is bounding back in its own direction. Instead of looking at the photographer, they are huddled next to each other, eyes wandering up and to the side.

It took me another decade and a half to realize the full horror of that photograph and what I had been told Idina had done. Another decade and a half of simmering fascination until, in the first years of this century, I had two small children of my own, of whom I possessed innumerable photographs standing side by side, at the same age that my grandfather and his brother had been when Idina had left. I thought of those little boys often at my own children’s bedtime, which caused me to linger, casting excess kisses into my little ones’ hair and giving in to their unending “Mummy, I need to tell you something. Just one last thing.” Idina, the person whom I yearned most to meet in an afterlife, had, according to my mother, done something that now made me feel quite sick.

Idina and Euan’s sons, Gerard (“Gee”), left, and David

But Idina was beneath my skin.

Just as I was beginning to fear the wear and tear of time myself, stories came to me of Idina’s ability to defy it. In her fifties, she showed not a trace of self-consciousness when removing her clothes; even after three children “she still had the full-breasted body of a thirty-five-year-old.”

30

At parties, she would walk into a room, “fix her big blue eyes on the man she wanted and, over the course of the evening, pull him into her web.”

31

One evening, in the 1940s, Idina sauntered into the rustic bar in the Gilgil Club, where an officers’ dance was in full swing. She slipped off her gold flip-flops and handed them to the barman, Abdul, asking him to “take these, and put them behind the bar,” walked across the floor, showing off still-perfect size five feet, and folded herself on a pile of cushions next to the twenty-something girl who would later tell me this story. Idina raised her hand, always heavy with the bulbous pearl

ring she wore, lit a cigarette, and, blowing immaculate smoke rings, informed the girl that “we share a boyfriend,”

32

making it clear that she held both a prior and a current claim that she did not intend to relinquish. The boyfriend in question was a twenty-four-year-old Army captain, thirty years younger than she was.

A great-grandmother sounds a long way away, but in Idina’s case it was not. Most families grow into a family tree branching out in several directions. The family between Idina and me, however, had been pollarded until all that was left was my mother and her sister, and several ungainly stumps where living relations should have been. Far from driving me away from her, the horror of what Idina had done in leaving her children magnified my need to know why she had left a husband she loved, and what had happened to her afterward.

And, oddly, stories abounded of that kindness referred to by Rosita Forbes and also of a woman who exuded maternal affection, wearing a big heart on her sleeve. “While my parents were away,” said one female friend, younger than Idina, “she looked after me so tenderly that I find it impossible to believe that she was anything but an adoring and excellent mother.”

33

This same woman made Idina godmother to her eldest child. So what had made her bolt from a husband she loved? Was there a story behind it, or was it just some impulse, an impulse that one day might resurface in me?

EVENTUALLY MY MOTHER HANDED ME

a large tin box containing Euan Wallace’s diaries—a regimented set bound in blue and red—together with two worn briefcases overflowing with photographs and letters. Some were from Idina. She always wrote in pencil. She couldn’t stand the mess of ink.

Her script was long and fluid, each letter the stroke of a violin bow, curling at the end. Her words, reaching across the page, thickened in my throat. “There is so little I can say for what are words when one has lost all one loves—thank God you have the children… How unutterably lonely you must be in your heart”—her words to her daughter-in-law trembled upon her son’s death.

34

Even within the breezeless still of a shuttered dining room, I held her letters tight, folded them, put them back in a pile weighted down, lest they should flutter away.

And out of these, and the attics of several other people’s houses and minds, tumbled the story of a golden marriage slowly torn apart during the First World War, and a divorce that reverberated throughout Idina’s life and still does today.

Chapter 2

T

he first upheaval in Idina’s life came early. She was four years old and her younger sister, Avice, called by all Avie at most, and Ave at worst, had just been born. Their mother, Muriel, exhausted from childbirth and her breasts overflowing with milk, was therefore not at her most sexually active. Idina’s father chose that moment to leave her for a cancan dancer.

Gilbert Sackville, Idina’s father and the eighth Earl De La Warr (pronounced Delaware) left the manor house in which he was living with his family in Bexhill-on-Sea. He moved a couple of streets away and into another property he owned. In this second house he installed the “actress” whom he had first espied through a haze of whisky and cigar fumes in the music hall on the seafront; a seafront which had been heavily subsidized with his wife’s family’s money. The year was 1897.

Idina’s parents had married each other for entirely practical reasons. Idina’s mother, Muriel Brassey, had wanted to become a countess. Gilbert, known as Naughty Gilbert to the generations that followed, had wanted Muriel’s money.

In a society that valued the antiquity of families and their money, Gilbert’s family was as old as a British family could be. Eight hundred years earlier they had followed William the Conqueror over from Normandy and been given enough land to live off the rent without having to put their hands to earning another penny. This is what was expected and, with just a couple of exceptions, in the intervening centuries

the family had done an immensely respectable little other than live off the fat income generated by its vast estates. The exceptions were two crucial flashes of glory in the now United States. One Lord De La Warr had rescued the starving Jamestown colonists in 1610, had been made governor of Virginia, and then had given his name to the state of Delaware. Another ancestor had been an early governor of New York, earning the earldom as a reward. But these men of action aside, Gilbert’s family had been remarkably quiet and, after eight hundred years, the money was running out.

Idina’s great-grandfather Thomas Brassey

Muriel’s family money had, in contrast, been made very recently and in the far less respectable middle-class activity of “Trade,” as it was snootily referred to by the upper classes who did not have to earn a living. And Muriel’s family’s Trade was now, far from discreetly, crisscrossing Britain in brand-new thick black lines. Muriel’s grandfather, Thomas Brassey, had employed eighty-five thousand men, more than the British Army, and had built one in every three miles of the railways laid in his lifetime. He had been an extraordinary man, for, despite the vast number of his employees, he had employed no secretary. Instead he had gone everywhere, even for a country walk, with a writing case, insisting that all correspondence be brought to him personally and immediately—even if he was standing in a field. He had opened each letter upon receipt and then sat down and composed an equally immediate reply. In the process he had made more money than any other self-made Englishman in the nineteenth century. Upon his death, in 1870, his financial estate, excluding any of his properties, was 6.5 million pounds, “the largest amount for which probate has been granted under any one will,” as Lord Derby wrote.

1