The Book of Basketball (100 page)

Read The Book of Basketball Online

Authors: Bill Simmons

Tags: #General, #History, #Sports & Recreation, #Sports, #Basketball - Professional, #Basketball, #National Basketball Association, #Basketball - United States, #Basketball - General

They relied on him at that advanced age for one reason: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was the surest two points in NBA history. Listed at 7-foot-2 but definitely two inches taller—at least

81

—his unstoppable sky hook remains the only basketball shot that couldn’t be blocked, an artistic achievement because of its consistency and efficiency. Every sky hook looked the same: in one motion, Kareem blocked off the defender with his left arm, swung his right arm over his head, reached as high as he could and flicked the basketball with his right wrist.

Swish.

Since defenders couldn’t dream of challenging the release, they settled on making him

miserable, pounding him like a blocking sled—with tacit approval from the officials, of course

82

—turning every 9-footer into a 13-footer and living with the odds from there. What else could they do? Kareem never needed a plan B, making him the

Groundhog Day

of NBA superstars. Fans struggled for ways to connect with him and failed, incapable of being thrilled by someone so predictable and aloof. Maybe it didn’t help that Kareem skipped the ’68 Olympics in protest of America’s racial climate,

83

or that he bristled at the public’s uneasiness about his religion and resented everyone’s impossibly high expectations. He handled every interview like he was disarming a hand grenade: too smart for dumb questions, too serious for frivolous jokes, too reserved for any semblance of personal candor. Unlike Chamberlain, he didn’t have a compulsive need to be loved; he just wanted to be left alone. And for the most part, that’s what fans did. When he changed his name a few weeks after Milwaukee won the ’71 title, the NBA’s dominant player was suddenly an introverted, intermittently sullen Muslim who towered over every center except Wilt, abhorred the press, relied on a robotic hook shot and pushed away the general public. You wouldn’t exactly throw in a “Good times!” to end the previous sentence.

(Note that’s too important to be a footnote: I always liked the fact that the best two athletes to adopt Muslim names happened to pick tremendously cool names—Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. According to the website for Muslim names that I just Googled twenty seconds ago, Kareem’s name means “generous, noble, friendly, precious and distinguished.” I will fight off the obligatory dig about the pomposity of that choice because I promised a potshot-free zone. But imagine if he’d picked “Khustar,” which means “surrounded by happiness.” Would Kareem have been as imposing with a name like Khustar Abdul-Jabbar? Probably not. What if he’d gone with Musharraf, which means “one who is honored or

exalted”? Musharraf Abdul-Jabaar? I don’t think so. Not to to sound like Colonel James, but Kareem Abdul-Jabbar … that’s a great fucking name! By the way, my favorite Muslim name on that website: Khasib means “fertile, productive, and profuse.” Should I make the Shawn Kemp joke or do you want to do it? Go ahead. You take it. Let’s move on.)

But that’s how it went through the 1970s. We kept hoping someone would supplant him and nobody did. Kareem’s public stature suffered for four unrelated reasons: the goofy combination of his afro, facial hair and goggles added to his detachment (it almost seemed like a Halloween mask); his trade demands (Milwaukee finally obliged in 1975) made him seem like just another petulant black athlete who wanted his way (the public perception, not the reality); 1977’s sucker punch of Kent Benson went over like a fart in church; and his ongoing battle with migraines made fans wonder if he was looking for excuses

not to

play. So what if the goggles were a result of his eyes getting poked so many times that doctors worried about permanent damage, that Benson elbowed him first, that Milwaukee had a lousy supporting cast and no Muslim population, that his headaches left him unable to function? Kareem never received the benefit of the doubt—not from anyone, not once, not ever. People grumbled that he didn’t give a crap, mailed in games, played on cruise control, failed to make teammates better and only cared about money. That perception faded once Magic turned the Lakers into the league’s most entertaining team, breathing life into Kareem’s career in the process.

Sports Illustrated

ran a January 1980 feature with the headline “A Different Drummer” and the subhead “After years of moody introspection, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is coming out of his shell.” He made a well-received cameo in a comedy called

Airplane

that blew everyone away, playing himself as a pilot with the alias “Roger Murdock.” A young passenger recognizes him and “Roger” denies it, leading to this exchange.

84

KID:

I think you’re the greatest, but my dad says you don’t work hard enough on defense. And he says that lots of times, you don’t even run down court. And that you don’t really try … except during the Playoffs.

KAREEM:

The hell I don’t. Listen, kid, I’ve been hearing that crap ever since I was at UCL.A. I’m out there busting my buns every night. Tell your old man to drag Walton and Lanier up and down the court for 48 minutes!

By his last scene, when Kareem was being lugged from the cockpit with his Laker uniform and goggles on, everyone had the same reaction.

Kareem has a sense of humor? What?

He would have cruised to 1980’s Comeback Personality of the Year Award if his single greatest playing moment—when he sprained an ankle in Game 5 of the ’80 Finals, limped back in with the Lakers trailing, finished off a 40-point performance on one leg and willed them to a crucial victory—hadn’t happened on tape delay and been overshadowed by Magic’s series-clinching 42–15–7 two days later.

85

Just like that, Kareem’s likability window had closed. The struggling Association moved forward with Bird and Magic, hitting its stride in the mid-eighties as Kareem settled into a new role as the aging, “How the hell is he still doing it?” superstar. And here’s where memories can be unfair: Kareem’s last six seasons (1984–89) unfortunately doubled as his most-seen stretch because the league’s TV ratings took off. Few remember him demolishing the ’71 Bullets, sinking the season-saving sky hook in double OT of the ’74 Finals or hobbling around to save the ’80 Finals; everyone remembers when he couldn’t rebound, couldn’t keep Moses off the boards (Kareem was thirty-six at the time, by the way), couldn’t protect the rim, slowed L.A.’s fast break, lost his hair and hung around for one awkward season too long. The thing that made him greater than Wilt—his staggering longevity—wounded the

perception

of his career after the fact. Wilt broke every record. Russell won eleven titles. Jordan dominated the nineties. Kareem? He’s the moody guy who peaked during the NBA’s darkest era and wouldn’t leave when it was time. What’s fun about celebrating that?

Since Kareem was measured against Wilt from the moment he started popping armpit hair, let’s keep the tradition going here. We already debunked

the myth about Wilt’s “inferior” supporting cast, but for the record, Wilt played with seven Pyramid guys (Greer, Arizin, West, Baylor, Cunningham, Thurmond and Goodrich) and Kareem played with five (Dandridge, Oscar, Worthy, McAdoo and Magic). Wilt’s supporting cast picked up for the last two-thirds of his career (1965–74); Kareem’s only picked up in the last half (1980–89). And Wilt never dealt with

anything

approaching Kareem’s shit sandwich in the 1970s, when his only elite teammates were Oscar (’71 and ’72), Dandridge (’71 through ’75) and Jamaal Wilkes (’78 and ’79). From ’73 through ’79, Kareem didn’t play with a single All-Star or elite point guard.

86

In twenty seasons, he only played with one power forward who averaged ten rebounds: the immortal Cornell Warner in 1975. When he dragged the ’74 Bucks to the Finals, their fourth and fifth leading “scorers” were Ron Washington and Jon McGlocklin. When the Lakers acquired him in the summer of ’75, they had to give up their best young players (Brian Winters, David Meyers and Junior Bridgeman) and left Kareem without a decent foundation. When he dragged the ’77 Lakers to the Western Finals without Kermit Washington and Lucius Allen (both injured), his crunch-time teammates were four piddling swingmen (Cazzie Russell, Earl Tatum, Don Chaney and Don Ford, with no rebounder or point guard to be seen).

87

Um, why is Wilt the one remembered as being “saddled” with a poor supporting cast again? Even Kareem admitted in 1980 to

SI

, “It’s the misunderstanding most people have about basketball that one man can make a team. One man can be a crucial ingredient on a team, but one man cannot make a team … [and] I have played on only three good teams.”

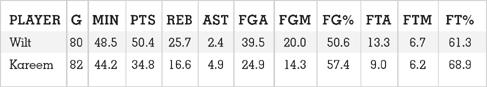

As for Wilt’s statistical “superiority,” we already established that the Dipper arrived during an optimal time: a mostly white league, no “modern” centers other than Russell, modified offensive goaltending, more possessions, and a less physical game that allowed him to play 48 minutes without any real physical repercussions. Those factors inflated his numbers, whereas Kareem’s only advantage from 1970 to 1976 was

dilution/overexpansion. Compare Wilt’s third season

(’62

, his best statistically) with Kareem’s third season (’72, his best statistically) and Wilt’s season looks significantly better on paper.

88

Then you keep digging:

1962 starting centers: Russell (Hall of Famer); Walt Bellamy, Wayne Embry, Johnny Kerr (quality starters); Clyde Lovellette, Darrall Imhoff, Walter Dukes, Ray Felix (stiffs)

1972 starting centers: Chamberlain, Reed, Cowens, Thurmond, Unseld, Lanier, Elvin Hayes, (Hall of Famers); Jim McDaniels, Bellamy, Elmore Smith, Tom Boerwinkle (quality starters); Neal Walk, Jim Fox, Bob Rule, Walt Wesley, Dale Schuleter (stiffs)

Throw in a dearth of athletic power forwards in ’62 and Wilt could run amok like the killer bear from

The Edge.

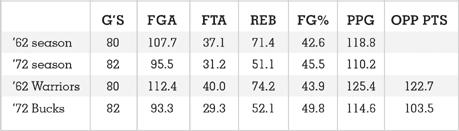

Kareem’s pivot opponents were undeniably better, as were the new wave of forwards fighting him for rebounds (Paul Silas, Bill Bridges, Clyde Lee, Happy Hairston, Connie Hawkins, Spencer Haywood, Sidney Wicks, Dave DeBusschere, Jerry Lucas and so on). As for the stylistic changes from 1962 to 1972:

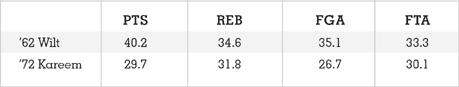

Can you say “statistical inflation”? Look at their percentages of their teams’ averages in the following categories.

To recap: Wilt scored 40 percent of his team’s points; Kareem scored 30 percent but did it more efficiently in a more physical era (57.4 percent shooting compared to Wilt’s 50.6 percent); Kareem grabbed just 2.8 percent less of his team’s available rebounds. Throw in Wilt’s era-specific advantages (covered earlier), all those extra Philly possessions (roughly 23–24 per game) and the difference in wins (63 for Milwaukee, 49 for Philly) and Kareem’s ’72 season may have been

more

impressive than Wilt’s legendary ’62 season. In fact, Kareem’s 35–17 has only been approached four times since 1972: McAdoo (31–15 in ’74, 34–14 in ’75), Moses (31–15 in ’82) and Shaq (30–14 in ’00). And it’s not like ’72 was a fluke: Kareem averaged at least a 30–16 for three straight years and topped 27 points and 14.5-plus rebounds in the same season six different times. In 97 playoff games from 1970 to 1981, Kareem

averaged

29.4 points and 15.2 rebounds.

89