The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are (7 page)

Read The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are Online

Authors: Alan Watts

Tags: #Self-knowledge; Theory of, #Eastern, #Self, #Philosophy, #Humanism, #General, #Religion, #Buddhism, #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Fiction, #Movements

This whole illusion has its history in ways of thinking—in the images, models, myths, and language systems which we have used for thousands of years to make sense of the world. These have had an effect on our perceptions which seems to be strictly hypnotic. It is largely by

talking

that a hypnotist produces illusions and strange behavioral changes in his subjects—talking coupled with relaxed fixation of the subject's conscious attention. The stage magician, too, performs most of his illusions by patter and misdirection of attention. Hypnotic illusions can be vividly sensuous and real to the subject, even after he has come out of the so-called "hypnotic trance."

It is, then, as if the human race had hypnotized or talked itself into the hoax of egocentricity. There is no one to blame but ourselves. We are not victims of a conspiracy arranged by an external God or some secret society of manipulators. If there is any biological foundation for

the hoax it lies only in the brain's capacity for narrowed, attentive consciousness hand-in-hand with its power of recognition—of knowing about knowing and thinking about thinking with the use of images and languages. My problem as a writer, using words, is to dispel the illusions of language while employing one of the languages that generates them. I can succeed only on the principle of "a hair of the dog that bit you."

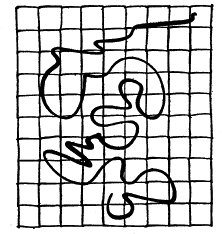

Apart from such human artifacts as buildings and roads (especially Roman and American roads), our universe, including ourselves, is thoroughly wiggly. Its features are wiggly in both shape and conduct.

Clouds, mountains, plants, rivers, animals, coastlines—all wiggle. They wiggle so much and in so many different ways that no one can really make out where one wiggle begins and another ends, whether in space or in time. Some French classicist of the eighteenth century complained that the Creator had seriously fallen down on the job by failing to arrange the stars with any elegant symmetry, for they seem to be sprayed through space like the droplets from a breaking wave. Is all this one thing wiggling in many different ways, or many things wiggling on their own? Are there "things" that wiggle, or are the wigglings the same as the things? It depends upon how you figure it.

Millennia ago, some genius discovered that such wiggles as fish and rabbits could be caught in nets. Much later, some other genius thought of catching the world in a net. By itself, the world goes something like this:

But now look at this wiggle through a net:

The net has "cut" the big wiggle into little wiggles, all contained in squares of the same size. Order has been imposed on chaos. We can now say that the wiggle goes so many squares to the left, so many to the right, so many up, or so many down, and at last we have its number.

Centuries later, the same image of the net was imposed upon the world as the lines of both celestial and terrestrial latitude and longitude, as graph paper for plotting mathematical wiggles, as pigeonholes for filing, and as the ground plan for cities. The net has thus become one of the presiding images of human thought. But it is always an image, and just as no one can use the equator to tie up a package, the real wiggly world slips like water through our imaginary nets. However much we divide, count, sort, or classify this wiggling into particular things and events, this is no more than a way of thinking about the world: it is never

actually

divided.

Another powerful image is the Ceramic Model of the universe, in which we think of it as so many forms of one or more substances, as pots are forms of clay, and as God is said to have created Adam from the dust. This has been an especially troublesome image, bewildering philosophers and scientists for centuries with such idiotic questions as:

"How does form (or energy) influence matter?" "What

is

matter?"

"What happens to form (the soul) when it leaves matter (the body)?"

"How is it that 'mere' matter has come to be arranged in orderly forms?"

"What is the relationship between mind and body?"

Problems that remain persistently insoluble should always be suspected as questions asked in the wrong way, like the problem of cause and effect. Make a spurious division of one process into two, forget that you have done it, and then puzzle for centuries as to how the two get together. So with "form" and "matter." Because no one ever discovered a piece of formless matter, or an immaterial form, it should have been obvious that there was something wrong with the Ceramic Model. The world is no more formed out of matter than trees are

"made" of wood. The world is neither form nor matter, for these are two clumsy terms for the same process, known vaguely as "the world" or

"existence." Yet the illusion that every form consists of, or is made of, some kind of basic "stuff" is deeply embedded in our common sense.

We have quite forgotten that both "matter" and "meter" are alike derived from the Sanskrit root

matr-

, "to measure," and that the "material" world means no more than the world as measured or measurable—by such abstract images as nets or matrices, inches, seconds, grams, and decibels. The term "material" is often used as a synonym for the word

"physical," from the Greek

physis

(nature), and the original Indo-European

bheu

(to become). There is nothing in the words to suggest that the material or physical world is made of any kind of stuff according to the Ceramic Model, which must henceforth be called the Crackpot Model.

But the Crackpot Model of the world as formed of clay has troubled more than the philosophers and the scientists. It lies at the root of the two major myths which have dominated Western civilization, and these, one following upon the other, have played an essential part in forming the illusion of the "real person."

If the world is basically "mere stuff" like clay, it is hard to imagine that such inert dough can move and form itself. Energy, form, and intelligence must therefore come into the world from outside. The lump must be leavened. The world is therefore conceived as an artifact, like a jar, a statue, a table, or a bell, and if it is an artifact, someone must have made it, and someone must also have been responsible for the original stuff. That, too, must have been "made." In Genesis the primordial stuff

"without form, and void" is symbolized as water, and, as water does not wave without wind, nothing can happen until the Spirit of God moves upon its face. The forming and moving of matter is thus attributed to intelligent Spirit, to a conscious force of energy in

form

ing matter so that its various shapes come and go, live and die.

Yet in the world as we know it, many things are clearly wrong, and one hesitates to attribute these to the astonishing Mind capable of making this world in the beginning. We are loath to believe that cruelty, pain, and malice come directly from the Root and Ground of Being, and hope fervently that God at least is the perfection of all that we can imagine as wisdom and justice. (We need not enter, here, into the fabulous and insoluble Problem of Evil which this model of the universe creates, save to note that it arises from the model itself.) The peoples who developed this myth were ruled by patriarchs or kings, and such superkings as the Egyptian, Chaldean, and Persian monarchs suggested the image of God as the Monarch of the Universe, perfect in wisdom and justice, love and mercy, yet nonetheless stern and exacting. I am not, of course, speaking of God as conceived by the most subtle Jewish, Christian, and Islamic theologians, but of the popular image. For it is the vivid image rather than the tenuous concept which has the greater influence on common sense.

The image of God as a personal Being, somehow "outside" or other than the world, had the merit of letting us feel that life is based on intelligence, that the laws of nature are everywhere consistent in that they proceed from

one

ruler, and that we could let our imaginations go to the limit in conceiving the sublime qualities of this supreme and perfect Being. The image also gave everyone a sense of importance and meaning. For this God is directly aware of every tiniest fragment of dust and vibration of energy, since it is just his awareness of it that enables it to be. This awareness is also love and, for angels and men at least, he has planned an everlasting life of the purest bliss which is to begin at the end of mortal time. But of course there are strings attached to this reward, and those who purposely and relentlessly deny or disobey the divine will must spend eternity in agonies as intense as the bliss of good and faithful subjects.

The problem of this image of God was that it became too much of a good thing. Children working at their desks in school are almost always put off when even a kindly and respected teacher watches over their shoulders. How much more disconcerting to realize that each single deed, thought, and feeling is watched by the Teacher of teachers, that nowhere on earth or in heaven is there any hiding-place from that Eye which sees all and judges all.

To many people it was therefore an immense relief when Western thinkers began to question this image and to assert that the hypothesis of God was of no help in describing or predicting the course of nature. If

everything,

they said, was the creation and the operation of God, the statement had no more logic than "Everything is up." But, as, so often happens, when one tyrant is dethroned, a worse takes his place. The Crackpot Myth was retained without the Potter. The world was still understood as an artifact, but on the model of an automatic machine.

The laws of nature were still there, but no lawmaker. According to the deists, the Lord had made this machine and set it going, but then went to sleep or off on a vacation. But according to the atheists, naturalists, and agnostics, the world was

fully

automatic. It had constructed itself, though not on purpose. The stuff of matter was supposed to consist of atoms like minute billiard balls, so small as to permit no further division or analysis. Allow these atoms to wiggle around in various permutations and combinations for an indefinitely long time, and at

some

time in virtually infinite time they will fall into the arrangement that we now have as the world. The old story of the monkeys and typewriters.

In this fully Automatic Model of the universe shape and stuff survived as energy and matter. Human beings, mind and body included, were parts of the system, and thus they were possessed of intelligence and feeling as a consequence of the same interminable gyrations of atoms. But the trouble about the monkeys with typewriters is that when at last they get around to typing the

Encyclopaedia Britannica,

they may at any moment relapse into gibberish. Therefore, if human beings want to maintain their fluky status and order, they must work with full fury to defeat the merely random processes of nature. It is most strongly emphasized in this myth that matter is brute and energy blind, that all nature outside human, and some animal, skins is a profoundly stupid and insensitive mechanism. Those who continued to believe in Someone-Up-There-Who-Cares were ridiculed as woolly-minded wishful thinkers, poor weaklings unable to face man's grim predicament in a heartless universe where survival is the sole privilege of the tough guys.

If the all-too-intelligent God was disconcerting, relief in getting rid of him was short-lived. He was replaced by the Cosmic Idiot, and people began to feel more estranged from the universe than ever. This situation merely reinforced the illusion of the loneliness and separateness of the ego (now a "mental mechanism") and people calling themselves naturalists began the biggest war on nature ever waged.

In one form or another, the myth of the Fully Automatic Model has become extremely plausible, and in some scientific and academic disciplines it is as much a sacrosanct dogma as any theological doctrine of the past—despite contrary trends in physics and biology. For there are fashions in myth, and the world-conquering West of the nineteenth century needed a philosophy of life in which

realpolitik—

victory for the tough people who face the bleak facts—was the guiding principle. Thus the bleaker the facts you face, the tougher you seem to be. So we vied with each other to make the Fully Automatic Model of the universe as bleak as possible.

Nevertheless it remains a myth, with all the positive and negative features of myth as an image used for making sense of the world. It is doubtful whether Western science and technology would have been possible unless we had tried to understand nature in terms of mechanical models. According to Joseph Needham, the Chinese—despite all their sophistication—made little progress in science because it never occurred to them to think of nature as mechanism, as "composed" of separable parts and "obeying" logical laws. Their view of the universe was organic. It was not a game of billiards in which the balls knocked each other around in a cause-and-effect series. What were causes and effects to us were to them "correlatives"—events that arose mutually, like back and front. The "parts" of their universe were not separable, but as fully interwoven as the act of selling with the act of buying.(1) A "made" universe, whether of the Crackpot or Fully Automatic Model, is made of bits, and the bits are the basic realities of nature.