The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are (10 page)

Read The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are Online

Authors: Alan Watts

Tags: #Self-knowledge; Theory of, #Eastern, #Self, #Philosophy, #Humanism, #General, #Religion, #Buddhism, #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Fiction, #Movements

The poets and sages have, indeed, been saying for centuries that success in this world is vanity. "The worldly hope men set their hearts upon turns ashes," or, as we might put it in a more up-to-date idiom, just when our mouth was watering for the ultimate goodie, it turns out to be a mixture of plaster-of-paris, papier-mâché, and plastic glue. Comes in any flavor. I have thought of putting this on the market as a universal substance, a

prima materia,

for making anything and everything—

houses, furniture, flowers, bread (they use it already), apples, and even people.

The world, they are saying, is a mirage. Everything is forever falling apart and there's no way of fixing it, and the more strenuously you grasp this airy nothingness, the more swiftly it collapses in your hands.

Western, technological civilization is, thus far, man's most desperate effort to beat the game—to understand, control, and fix this will-o'-the-wisp called life, and it may be that its very strength and skill will all the more rapidly dissolve its dreams. But if this is not to be so, technical power must be in the hands of a new kind of man.

In times past, recognition of the impermanence of the world usually led to withdrawal. On the one hand, ascetics, monks, and hermits tried to exorcise their desires so as to regard the world with benign resignation, or to draw back and back into the depths of consciousness to become one with the Self in its unmanifest state of eternal serenity.

On the other hand, others felt that the world was a state of probation where material goods were to be used in a spirit of stewardship, as loans from the Almighty, and where the main work of life is loving devotion to God and to man.

Yet both these responses are based on the initial supposition that the individual is the separate ego, and because this supposition is the work of a double-bind any task undertaken on this basis—including religion—will be self-defeating. Just because it is a hoax from the beginning, the personal ego can make only a phony response to life. For the world is an ever-elusive and ever-disappointing mirage only from the standpoint of someone standing aside from it—as if it were quite other than himself—and then trying to grasp it. Without birth and death, and without the perpetual transmutation of all forms of life, the world would be static, rhythmless, undancing, mummified.

But a third response is possible. Not withdrawal, not stewardship on the hypothesis of a

future

reward, but the fullest collaboration with the world as a harmonious system of contained conflicts—based on the realization that the only real "I" is the whole endless process. This realization is already in us in the sense that our bodies know it, our bones and nerves and sense-organs. We do not know it only in the sense that the thin ray of conscious attention has been taught to ignore it, and taught so thoroughly that we are very genuine fakes indeed.

(1) "Until the middle of the 17th century Chinese and European scientific theories were about on a par, and only thereafter did European thought begin to move ahead so rapidly. But though it marched under the banner of Cartesian-Newtonian mechanicism, that viewpoint could not permanently suffice for the needs of science—

the time came when it was imperative to look upon physics as the study of the smaller organisms, and biology as the study of the larger organisms. When the time came, Europe (or rather; by then, the world) was able to draw upon a mode of thinking very old, very wise, and not characteristically European at all." Needham,

Science and

Civilisation in China

. Cambridge University Press, 1956. Vol. II, p. 303.

(2) This is not to be taken as a rejection of "modern art" in general, but only of that rather dominant aspect of it which claims that the artist should represent his time. And since this is the time of junkyards, billboards, and expensive slums, many artists—

otherwise bereft of talent—make a name for themselves by the "tasteful" framing or pedestaling of

objets trouvés

from the city dump.

THE WORLD IS YOUR BODY

WE HAVE now found out that many things which we felt to be basic realities of nature are social fictions, arising from commonly accepted or traditional ways of thinking about the world. These fictions have included:

1. The notion that the world is made up or composed of separate bits or things.

2. That things are differing forms of some basic stuff.

3. That individual organisms are such things, and that they are inhabited and partially controlled by independent egos.

4. That the opposite poles of relationships, such as light/darkness and solid/space, are in actual conflict which may result in the permanent victory of one of the poles.

5. That death is evil, and that life must be a constant war against it.

6. That man, individually and collectively, should aspire to be top species and put himself in control of nature.

Fictions are useful so long as they are taken as fictions. They are then simply ways of "figuring" the world which we agree to follow so that we can act in cooperation, as we agree about inches and hours, numbers and words, mathematical systems and languages. If we have no agreement about measures of time and space, I would have no way of making a date with you at the corner of Forty-second Street and Fifth Avenue at 3 P.M. on Sunday, April 4.

But the troubles begin when the fictions are taken as facts. Thus in 1752 the British government instituted a calendar reform which required that September 2 of that year be dated September 14, with the result that many people imagined that eleven days had been taken off their lives, and rushed to Westminster screaming, "Give us back our eleven days!"

Such confusions of fact and fiction make it all the more difficult to find wider acceptance of common laws, languages, measures, and other useful institutions, and to improve those already employed.

But, as we have seen, the deeper troubles arise when we confuse ourselves and our fundamental relationships to the world with fictions (or figures of thought) which are taken for granted, unexamined, and often self-contradictory. Here, as we have also seen, the "nub" problem is the self-contradictory definition of man himself as a separate and independent being

in

the world, as distinct from a special action of the world. Part of our difficulty is that the latter view of man seems to make him no more than a puppet, but this is because, in trying to accept or understand the latter view, we are still in the grip of the former. To say that man is an action of the world is not to define him as a "thing" which is helplessly pushed around by all other "things." We have to get beyond Newton's vision of the world as a system of billiard balls in which every individual ball is passively knocked about by all the rest!

Remember that Aristotle's and Newton's preoccupation with casual determinism was that they were trying to explain how one thing or event was influenced by others, forgetting that the division of the world into separate things and events was a fiction. To say that certain events are casually connected is only a clumsy way of saying that they are features of the same event, like the head and tail of the cat.

It is essential to understand this point thoroughly: that the thing-in-itself (Kant's

Ding an sich

), whether animal, vegetable, or mineral, is not only unknowable—it does not exist. This is important not only for sanity and peace of mind, but also for the most "practical" reasons of economics, politics, and technology. Our practical projects have run into confusion again and again through failure to see that individual people, nations, animals, insects, and plants do not exist in or by themselves.

This is not to say only that things exist in relation to one another, but that what we call "things" are no more than glimpses of a unified process. Certainly, this process has distinct features which catch our attention, but we must remember that distinction is not separation. Sharp and clear as the crest of the wave may be, it necessarily "goes with" the smooth and less featured curve of the trough. So also the bright points of the stars "gowith" (if I may now coin a word) the dark background of space.

In the Gestalt theory of perception this is known as the figure/ground relationship. This theory asserts, in brief, that no figure is ever perceived except in relation to a background. If, for example, you come so close to me that the outline of my body lies beyond your field of vision, the

"thing" you will see will no longer be my body. Your attention will instead be "captured" by a coat-button or a necktie, for the theory also asserts that, against any given background, our attention is almost automatically "won" by any moving shape (in contrast with the stationary background) or by any enclosed or tightly complex feature (in contrast with the simpler, featureless background).

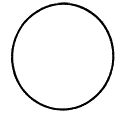

Thus when I draw the following figure on a blackboard—

and ask, "What have I drawn?" people will generally identify it as a circle, a ball, a disk, or a ring. Only rarely will someone reply, "A wall with a hole in it."

In other words, we do not easily notice that all features of the world hold their boundaries in common with the areas that surround them—

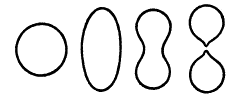

that the outline of the figure is also the inline of the background. Let us suppose that my circle/hole figure were to move through the following series of shapes:

Most people would thereupon ascribe the movement, the act, to the enclosed area as if it were an amoeba. But I might just as well have been drawing the dry patches in a thin film of water spread over a polished table. But the point is that, in either case, the movement of any feature of the world cannot be ascribed to the outside alone or to the inside alone. Both move together.

Our difficulty in noticing both the presence and the action of the background in these simple illustrations is immensely increased when it comes to the behavior of living organisms. When we watch ants scurrying hither and thither over a patch of sand, or people milling around in a public square, it seems absolutely undeniable that the ants and the people are alone responsible for the movement. Yet in fact this is only a highly complex version of the simple problem of the three balls moving in space, in which we had to settle for the solution that the entire configuration (Gestalt) is moving—not the balls alone, not the space alone, not even the balls and the space together in concert, but rather a single field of solid/space of which the balls and the space are, as it were, poles.

The illusion that organisms move entirely on their own is immensely persuasive until we settle down, as scientists do, to describe their behavior carefully. Then the scientist, be he biologist, sociologist, or physicist, finds very rapidly that he cannot say what the organism is doing unless, at the same time, he describes the behavior of its surroundings. Obviously, an organism cannot be described as walking just in terms of leg motion, for the direction and speed of this walking must be described in terms of the ground upon which it moves.

Furthermore, this walking is seldom haphazard. It has something to do with food-sources in the area, with the hostile or friendly behavior of other organisms, and countless other factors which we do not immediately consider when attention is first drawn to a prowling ant.

The more detailed the description of our ant's behavior becomes, the more it has to include such matters as density, humidity, and temperature of the surrounding atmosphere, the types and sources of its food, the social structure of its own species, and that of neighboring species with which it has some symbiotic or preying relationship.

When at last the whole vast list is compiled, and the scientist calls

"Finish!" for lack of further time or interest, he may well have the impression that the ant's behavior is no more than its automatic and involuntary reaction to its environment. It is attracted by this, repelled by that, kept alive by one condition, and destroyed by another. But let us suppose that he turns his attention to some other organism in the ant's neighborhood—perhaps a housewife with a greasy kitchen—he will soon have to include that ant, and all its friends and relations, as something which determines

her

behavior! Wherever he turns his attention, he finds, instead of some positive, causal agent, a merely responsive hollow whose boundaries go this way and that according to outside pressures.