The Book Thief (25 page)

Authors: Markus Zusak

Tags: #Fiction, #death, #Storytelling, #General, #Europe, #Historical, #Juvenile Fiction, #Holocaust, #Children: Young Adult (Gr. 7-9), #Religious, #Books and reading, #Historical - Holocaust, #Social Issues, #Jewish, #Books & Libraries, #Military & Wars, #Books and reading/ Fiction, #Storytelling/ Fiction, #Historical Fiction (Young Adult), #Death & Dying, #Death/ Fiction, #Juvenile Fiction / Historical / Holocaust

In late

February, when Liesel woke up in the early hours of morning, a figure made its

way into her bedroom. Typical of Max, it was as close as possible to a

noiseless shadow.

February, when Liesel woke up in the early hours of morning, a figure made its

way into her bedroom. Typical of Max, it was as close as possible to a

noiseless shadow.

Liesel, searching

through the dark, could only vaguely sense the man coming toward her.

through the dark, could only vaguely sense the man coming toward her.

“Hello?”

There was no

reply.

reply.

There was

nothing but the near silence of his feet as he came closer to the bed and

placed the pages on the floor, next to her socks. The pages crackled. Just

slightly. One edge of them curled into the floor.

nothing but the near silence of his feet as he came closer to the bed and

placed the pages on the floor, next to her socks. The pages crackled. Just

slightly. One edge of them curled into the floor.

“Hello?”

This time there

was a response.

was a response.

She couldn’t

tell exactly where the words came from. What mattered was that they reached

her. They arrived and kneeled next to the bed.

tell exactly where the words came from. What mattered was that they reached

her. They arrived and kneeled next to the bed.

“A late birthday

gift. Look in the morning. Good night.”

gift. Look in the morning. Good night.”

For a while, she

drifted in and out of sleep, not sure anymore whether she’d dreamed of Max

coming in.

drifted in and out of sleep, not sure anymore whether she’d dreamed of Max

coming in.

In the morning,

when she woke and rolled over, she saw the pages sitting on the floor. She

reached down and picked them up, listening to the paper as it rippled in her

early-morning hands.

when she woke and rolled over, she saw the pages sitting on the floor. She

reached down and picked them up, listening to the paper as it rippled in her

early-morning hands.

All my life,

I’ve been scared of men standing over me. . . .

I’ve been scared of men standing over me. . . .

As she turned

them, the pages were noisy, like static around the written story.

them, the pages were noisy, like static around the written story.

Three days, they

told me . . . and what did I find when I woke up?

told me . . . and what did I find when I woke up?

There were the

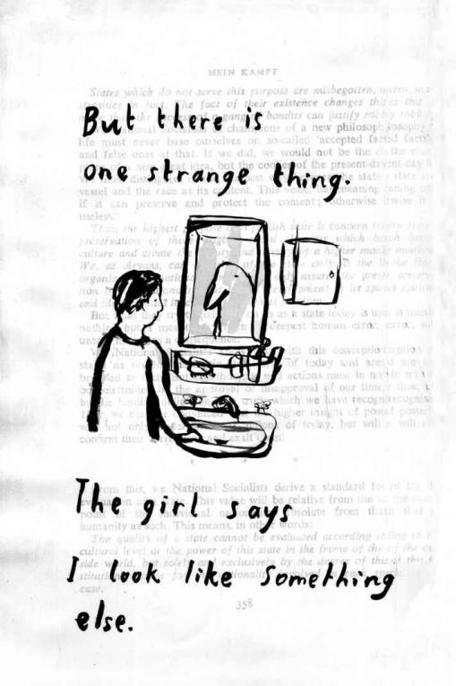

erased pages of

Mein Kampf,

gagging, suffocating under the paint as they

turned.

erased pages of

Mein Kampf,

gagging, suffocating under the paint as they

turned.

It makes me

understand that the best standover man I’ve ever known . . .

understand that the best standover man I’ve ever known . . .

Liesel read and

viewed Max Vandenburg’s gift three times, noticing a different brush line or

word with each one. When the third reading was finished, she climbed as quietly

as she could from her bed and walked to Mama and Papa’s room. The allocated

space next to the fire was vacant.

viewed Max Vandenburg’s gift three times, noticing a different brush line or

word with each one. When the third reading was finished, she climbed as quietly

as she could from her bed and walked to Mama and Papa’s room. The allocated

space next to the fire was vacant.

As she thought

about it, she realized it was actually appropriate, or even better—perfect—to

thank him where the pages were made.

about it, she realized it was actually appropriate, or even better—perfect—to

thank him where the pages were made.

She walked down

the basement steps. She saw an imaginary framed photo seep into the wall—a

quiet-smiled secret.

the basement steps. She saw an imaginary framed photo seep into the wall—a

quiet-smiled secret.

No more than a

few meters, it was a long walk to the drop sheets and the assortment of paint

cans that shielded Max Vandenburg. She removed the sheets closest to the wall

until there was a small corridor to look through.

few meters, it was a long walk to the drop sheets and the assortment of paint

cans that shielded Max Vandenburg. She removed the sheets closest to the wall

until there was a small corridor to look through.

The first part

of him she saw was his shoulder, and through the slender gap, she slowly,

painfully, inched her hand in until it rested there. His clothing was cool. He

did not wake.

of him she saw was his shoulder, and through the slender gap, she slowly,

painfully, inched her hand in until it rested there. His clothing was cool. He

did not wake.

She could feel

his breathing and his shoulder moving up and down ever so slightly. For a

while, she watched him. Then she sat and leaned back.

his breathing and his shoulder moving up and down ever so slightly. For a

while, she watched him. Then she sat and leaned back.

Sleepy air

seemed to have followed her.

seemed to have followed her.

The scrawled

words of practice stood magnificently on the wall by the stairs, jagged and

childlike and sweet. They looked on as both the hidden Jew and the girl slept,

hand to shoulder.

words of practice stood magnificently on the wall by the stairs, jagged and

childlike and sweet. They looked on as both the hidden Jew and the girl slept,

hand to shoulder.

They breathed.

German and

Jewish lungs.

Jewish lungs.

Next to the

wall,

The Standover Man

sat, numb and gratified, like a beautiful itch

at Liesel Meminger’s feet.

wall,

The Standover Man

sat, numb and gratified, like a beautiful itch

at Liesel Meminger’s feet.

PART FIVE

the

whistler

whistler

featuring:

a floating book—the gamblers—a small ghost—

two haircuts—rudy’s youth—losers and sketches—

a whistler and some shoes—three acts of stupidity—

and a frightened boy with frozen legs

THE FLOATING BOOK (Part I)

A book floated

down the Amper River.

down the Amper River.

A boy jumped in,

caught up to it, and held it in his right hand. He grinned.

caught up to it, and held it in his right hand. He grinned.

He stood

waist-deep in the icy, Decemberish water.

waist-deep in the icy, Decemberish water.

“How about a

kiss,

Saumensch

?” he said.

kiss,

Saumensch

?” he said.

The surrounding

air was a lovely, gorgeous, nauseating cold, not to mention the concrete ache

of the water, thickening from his toes to his hips.

air was a lovely, gorgeous, nauseating cold, not to mention the concrete ache

of the water, thickening from his toes to his hips.

How about a

kiss?

kiss?

How about a

kiss?

kiss?

Poor Rudy.

A

SMALL ANNOUNCEMENT

SMALL ANNOUNCEMENT

ABOUT RUDY STEINER

He didn’t deserve to die the way he did.

In your visions,

you see the sloppy edges of paper still stuck to his fingers. You see a

shivering blond fringe. Preemptively, you conclude, as I would, that Rudy died

that very same day, of hypothermia. He did not. Recollections like those merely

remind me that he was not deserving of the fate that met him a little under two

years later.

you see the sloppy edges of paper still stuck to his fingers. You see a

shivering blond fringe. Preemptively, you conclude, as I would, that Rudy died

that very same day, of hypothermia. He did not. Recollections like those merely

remind me that he was not deserving of the fate that met him a little under two

years later.

On many counts,

taking a boy like Rudy was robbery—so much life, so much to live for—yet

somehow, I’m certain he would have loved to see the frightening rubble and the

swelling of the sky on the night he passed away. He’d have cried and turned and

smiled if only he could have seen the book thief on her hands and knees, next

to his decimated body. He’d have been glad to witness her kissing his dusty,

bomb-hit lips.

taking a boy like Rudy was robbery—so much life, so much to live for—yet

somehow, I’m certain he would have loved to see the frightening rubble and the

swelling of the sky on the night he passed away. He’d have cried and turned and

smiled if only he could have seen the book thief on her hands and knees, next

to his decimated body. He’d have been glad to witness her kissing his dusty,

bomb-hit lips.

Yes, I know it.

In the darkness

of my dark-beating heart, I know. He’d have loved it, all right.

of my dark-beating heart, I know. He’d have loved it, all right.

You see?

Even death has a

heart.

heart.

THE GAMBLERS

(A

SEVEN-SIDED DIE)

SEVEN-SIDED DIE)

Of course, I’m

being rude. I’m spoiling the ending, not only of the entire book, but of this

particular piece of it. I have given you two events in advance, because I don’t

have much interest in building mystery. Mystery bores me. It chores me. I know

what happens and so do you. It’s the machinations that wheel us there that

aggravate, perplex, interest, and astound me.

being rude. I’m spoiling the ending, not only of the entire book, but of this

particular piece of it. I have given you two events in advance, because I don’t

have much interest in building mystery. Mystery bores me. It chores me. I know

what happens and so do you. It’s the machinations that wheel us there that

aggravate, perplex, interest, and astound me.

There are many

things to think of.

things to think of.

There is much

story.

story.

Certainly,

there’s a book called

The Whistler,

which we really need to discuss,

along with exactly how it came to be floating down the Amper River in the time

leading up to Christmas 1941. We should deal with all of that first, don’t you

think?

there’s a book called

The Whistler,

which we really need to discuss,

along with exactly how it came to be floating down the Amper River in the time

leading up to Christmas 1941. We should deal with all of that first, don’t you

think?

It’s settled,

then.

then.

We will.

It started with

gambling. Roll a die by hiding a Jew and this is how you live. This is how it

looks.

gambling. Roll a die by hiding a Jew and this is how you live. This is how it

looks.

Other books

Cuidado con esa mujer by David Goodis

Strip Search by Shayla Black

The Silence of the Sea by Yrsa Sigurdardottir

Dark of the Moon by Barrett, Tracy

Laura Meets Jeffrey by Jeffrey Michelson, Laura Bradley

The Wonder by J. D. Beresford

Hewitt: Jagged Edge Series #1 by A.L. Long

Edith Layton by To Tempt a Bride

Mystery of the Dark Tower by Evelyn Coleman