The Brooke-Rose Omnibus (71 page)

Read The Brooke-Rose Omnibus Online

Authors: Christine Brooke-Rose

Oh Armel that’s a lovely pun you kill me I just can’t be angry with you.

Why the hell should you be I’m the one who’s angry who was he anyway?

Are you, Armel?

Answer me.

Nigger bastard.

Oh no don’t you misuse the code now we’re not in an erotic situation.

Aaaaren’t we Arme-e-e-e-el?

No damn you Jewish slut

Nigger bastard decoding brown into pink mouth four eyes aslant black white limbs winding in and out over and under each other vertical horizontal diagonal swiftly changing positions swaying undoing and floating up every ninety minutes or so under loaded lids for a shared who was he anyway was he white was he any good?

Armel! You, jealous?

No. Just, outraged

What the heck’s the difference?

in my mythical aura. What’s the big idea telling me all those dreams if

Oh come off it Armel you’re the one who insisted no regular petty boorjwah arrangement no planning and that all spontaneous like and you never ring and half the time you’re busy and I’m just crazy for you so what can I do the night after’s the only night I know you’re not

Okay okay was he any good?

What d’you think after just now?

So? Why then?

You don’t understand a thing do you. I promised not to fall in love not to make scenes and complications casual you wanted it so okay casual it is that cuts both ways or are you for the double standard you male showvinist and black at that. And you treat me like dirt at best a mildly amusing air-filling sex-object and make me pursue you well I’m a woman and okay I can pursue and be turned down and all but only up to a point so when a goy-boy crazy for it won’t leave me alone and begs for it and turns up at all hours of the night not when I’m here he doesn’t okay so he’s selfish too and assumes I’m always available and so I am thanks to you and he comes too quick and goes and he’s only using me to get confidence so’s he can pass it on to the fresher flesh of little girls less good at it than me and I teach him plenty and say in effect go forth and multiply I have no illusions but for the moment he pursues me and I like it see?

She cries her black hair over her white arm.

Abstention. Refusal of votive offering.

Do you always make love in your watch?

Yeah. Just like you always take yours off. I love you Armel I’m sorry.

Have a puff.

No thanks finish it.

I never noticed.

What?

Your watch. Funny that. Like Gulliver.

Gulliver. Who’s he when he’s at home?

Precisely at home. Couldn’t stand the human smell of his wife after living with talking horses and fell into a swoon, for two hours he says, implying that he looked at his watch as he went down. There’s empiricism for you.

Oh very signif I’m sure. The man always takes his off, pretends it’s out of time I guess so it doesn’t count.

I just don’t want to hurt you.

You can say that again. The boy left his behind once I was idiot-happy about it till I remembered a big middle aged man at the office I was crazy about he’s left now, a cautious pussy-cat wouldn’t make firm dates either not like you though just frightened so he’d wrap it up in vagueness I must protect myself he said like I was going to eat him.

Eurilochus.

I’m what?

Nothing. Something Larissa said once.

Clarissa? Who’s she when she’s at home?

No one. Someone I used to know.

You never told me about her.

Go on about the middle-aged man. Did he take his watch off?

Course he did. And he left it behind once together with his fountain-pen or was it a biro that dropped behind the bed and I took’m to him next day and teased him what would Freud say to that I said and he looked kinda sore and took’m and walked to the door and just as he opened it like he wanted everyone to hear he turned round and said he’d say I suppose that I’d spent the night in your bed. Annoyed? I was parannoyed. Well I mean I wouldn’t have minded if he’d come out with it quick as a flash like you would adding maybe elementary my dear Watson like Freud was Sherlock Holmes but it was more a doubletake, slow and heavy, jocular and kinduv friendly you know on the surface but supercilious really and with the door open so’s anyone could hear. I lost him soon after that. I always lose my men just like I’ll lose the boy and I’m losing you. So how can the watch mean a damn thing?

You read what you want into it.

Oh yeah?

You know very well, Ruth, that everyone, you, me, anyone, gets the treatment they ask for, they unconsciously want as you’re so fond of saying.

| | Yea, sure. So? Jewish slut. Nigger bastard. | |

| | | Myra Kaplan Second Semester |

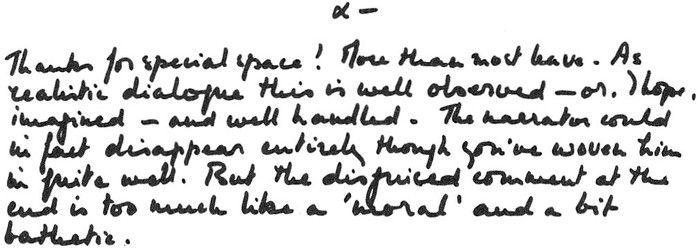

| | Comments by Dr. Sartores | Exercise: dialogue |

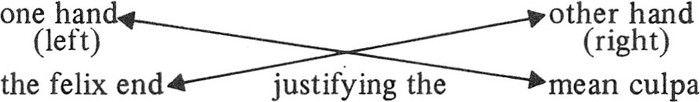

Well at least it has got the elements of narrative moving a bit even at the cost of the bathetic fallacy filling the heremeneutic gap but, on the other hand, enabling the original asymmetrical subject of discourse who does not see the four lies in the retrovizor to be tactfully dropped without scene full of summary, as was forescene she having initially accepted her momentary status. Thus the cost is balanced on the

(though of course when the account is transferred to the viewpoint of the object exchanged the debit goes to the left and the credit to the right).

Either way the economy of the narrative is preserved via the Value theorem of Valincour.*

*Il est temps de rappeller ici que d’excellents érudits attribuent la paternité réelle des Lettres sur la Princesse de Clèves non pas à Valincour mais au P. Bouhours, S.J.**

** portrait of the paternity of the Value theorem by Gérard Genette***

***Boohoo to paternity S.J.: in the interests of narrative economy and of abolishing private property all plagiarisms will presently be unacknowledged.

To return to the subject of discourse: the arbitrariness (liberty) of narrative is not infinite. The narrator chooses the middle of his sentence (his kernel narrative sentence of course we’re not speaking of real sentences) in function of its end

Contrary then to Brémond on Propp’s functions who says that although from the point of view of la parole the end of the sentence commands its first words, we should adopt the point of view of la langue in which the beginning of the sentence commands the end, thus opening the whole network of possibilities in which we can then construct our sequences of functions.

Yes there is a contradiction there Ali, quite right. But that was in the beginnings of narrative analysis, I think Brémond has moved on. To return to Genette, the arbitrariness of narrative is its functionality

You said it was liberty

At the beginning of his argument yes. But he too has moved on and we with him I hope. Are you following this?

Liberté, égalité, fonctionnalité.

Functionality, he means, as opposed to motivation, which is an a posteriori justification of the form that has determined it.

I don’t understand.

No I don’t either.

Well, there’s a diametrical opposition between the function of an element–what it is used for–and its motivation–what is necessary to conceal the function. As Genette puts it, the prince de Clèves does not die because his gentilhomme has behaved like a fool, though that is how it seems, his gentilhomme behaves like a fool so that the prince de Clèves can die.

Oh yes, it’s like the Knight in the Tiger Skin.

Exactly. So the productivity of a narrative element–its yield or profit or Value–will consist of the difference between Function and Motivation: V = F – M. An implicit Motivation costs nothing and will give V = F – O, i.e. V = F. Neat isn’t it?

Isn’t he falling into the capitalist trap by using its language?

I don’t think so Robert. Literature is an object of exchange, a merchandise like any other, and works according to the same principles of economy, which we might as well understand. As does language.

As does teaching then?

Certainly.

But Socrates didn’t take any money as he kept repeating in his apology, contrary to the Sophists.

I wasn’t referring to the money exchange, Ali, so much as to the internal principles of exchange with what the receptor is prepared to give and take, not just in money but in effort and reward. You might say that Socrates was selling Virtue, Truth and Beauty etc. in return for a certain ability and pleasure in dialectic. But to return to yes Saroja?

That explanation, I mean V = F and all that is surely itself an a posteriori justification of the narrative and therefore a motivation?

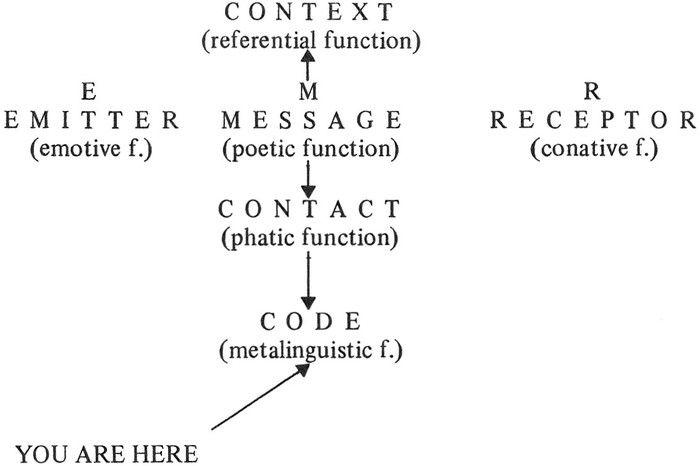

And a costly one you mean? A very good point. But we mustn’t confuse the levels of discourse. My function here is not to narrate but to teach, or shall we say I am not a function of your narrative, and we are using a metalanguage, so:

(Unless you have gotten imprisoned in M)

There should be placards saying: Danger. You are now entering the Metalinguistic Zone. All access forbidden except for Prepared Consumers with special permits from the Authorities.

M-phatically.

And if one settling a pillow by her head should say that is not what I meant at all that is not it at all you can brusquely scrub the diagram and disappear altogether, though admittedly that is only a manner of speaking since the text has somehow come into existence

as an insistant instance

it happened in Europe last summer. I

had driven from Strasburg where I showed my passport and car documents at the frontier and then I had a minor accident in Augsburg having stopped at a stop sign just as the chap behind me didn’t. After the usual exchange of insurance identities I drove on across Austria into Italy where I suddenly discovered that I no longer had my car documents so I went to the local police station in the next village and there the Maresciallo Capo Commendatore listened to my story and as he had no assistance he himself typed out the Dichiarazione di Smarrimento quite fast with two fingers. It was taking so long however that I asked him with a smile: “Lei scrive un romanzo?” And he replied with a Latin shrug: “Ma, devo raccontare qualcosa”. This amused me very much and seems to me to symbolize all the narrator’s problems we have been studying this semestre especially as he got it all wrong saying the smarrimento may have occurred during an incidente stradale in Strasburg which even if he had got the town right was a supposition on his part with no legal validity on such a document in other words pure fiction.