The Brooke-Rose Omnibus (70 page)

Read The Brooke-Rose Omnibus Online

Authors: Christine Brooke-Rose

for that matter does it mention Larissa

who is the second person singular

keeping her I

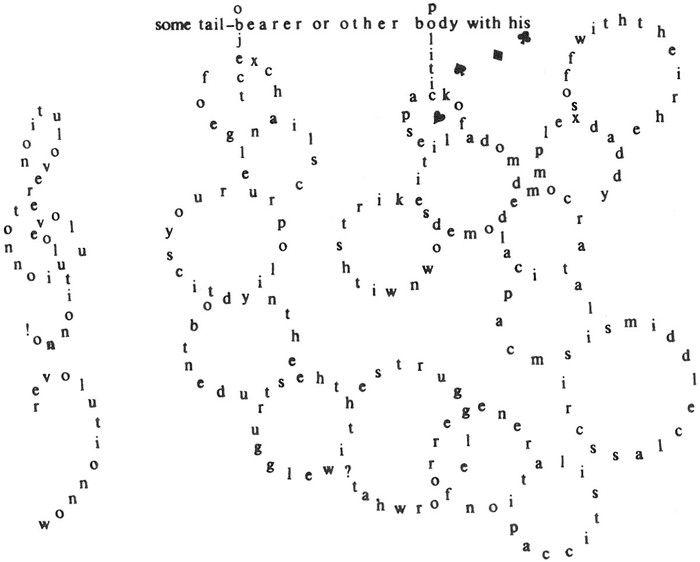

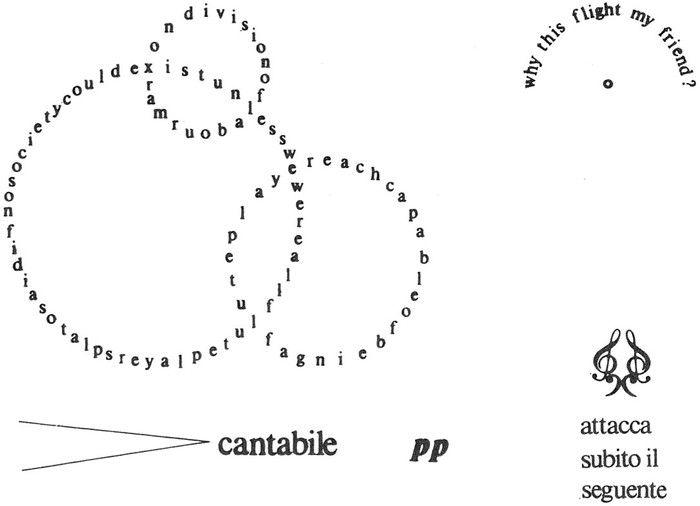

So that today we shall try to work out a typology of digressive utterance by a narrator like Tristram Shandy who inscribes himself into his text as subject struggling with various levels of his own discourse. But is he not also an intransitivitised subject walking through the inaction with indirect objects only or none? Every structure presupposes a void, into which it is possible to fall, rehandling the signifiers over and over into acceptability, itself subject to memory and constant mutation as the subject-actant undergoes its transformations, each level of utterance generating another. This is an ancient technique, derived perhaps from agglomerated tales, you know, ten a day for a hundred days. You remember that 12th century Georgian romance we read, The Knight in the Tiger Skin, where each character has to tell his story–after much coy resistance–in order in fact that Tariel’s quest may proceed. But as we saw the motivation can be reversed, Tariel being a passive and extraordinarily helpless hero who lets his friends hunt the heroine for him, in order that each story may be told. The initial story of the knight is practically forgotten. Better known and more significant is Scheherezade, whose very life is to narrate and whose narration gives her life, with every new character in the same situation, not a character but a tale-bearer, whose life also depends on his narration generated by the surplus value left over from the previous tale and itself generating the next. Read Todorov les hommes-récits on this. Each I leads into another I, unless I into O for Other interruption with a point of information?

Of course.

Oh no! Go away take your politics elsewhere we want to work.

Let them speak at least, it’s a free country.

Who sez?

Go ahead please. In this text everyone has a voice.

Brother I thank you well as you all know some of our comrades were arrested in the demo yesterday and we have called a strike of all

Who’s we?

A majority of over a thousand to sixty-seven at the General Assembly.

Okay and there are over fifteen thousand students in the university

Yeah and where were they? If they’re not concerned with the iniquitous situation resulting from authoritarian decrees in a society which serves only the interests of capitalism

Cant!

and conspicuous consumption

Go consume yourself

hear hear

them out they’re right

Who sez?

The problem is then for the narrator to get back to his initial subject, if he wants to of course, as clearly Tristram does, and on his own surface structure assumption that his Life and Opinions are his subject. Now:

Supposing you had started telling a story, which digressed into another and yet another, how would you go about returning to the first unfinished story? You could work back towards S, here, through other digressions, in a wide circular pattern, so. Or backwards through the same digressions, like returning through the same doors, so.

Digression in fact, has the same structure as any action or adventure. As when you have followed one character and want to return to another. You remember the guinea-pig simile in I

promessi

sposi.

No? I have it here I will read it. I have often watched a boy (a dear little fellow, almost too high-spirited then, really, but showing every sign of growing up into a decent citizen one day) ((uuugh)) busy driving his herd of guinea-pigs into their pen towards evening, after letting them run about free all day in a little orchard. He would try to get them all into the pen together, but it was labour wasted: one of them would stray off to the right, and as the little drover was running about to get it back into the herd, another, then two, then three others would go scurrying off all over the place to the left. Finally, after getting somewhat impatient, he would adapt himself to their ways, and push the ones nearest the door in first, then go and get the others, in ones or twos or threes, as best he could. We have to play the same sort of game with our characters; once we had Lucia under cover, we hurried off to Don Rodrigo; and now we must leave him to follow up Renzo, of whom we had lost sight.

A quaint long-winded way of expressing the linearity of the text. And a false simile if you think about it since characters do not run about like guinea-pigs when abandoned by the author but remain suspended in a fictive illusion to be recreated by flashback more or less well camouflaged.

Camouflashback.

Who speaks then, Tristram Tariel (or Manzoni or Chota Rustaveli or Queen Thamar?) Lending his signifiers to a character who does not exist but nevertheless switches on the overhead projector to draw rewrite-arrows or transformational trees of embedded digressions or maybe rectangles with a spirit-loaded pen thus not losing I-contact through to the convolutions of twenty-seven brains he dips into and caresses with a point of interest built up at the flick of a switch into a diagram of digressions like doors leading into one another then scrubbed as soon as copied down to be replaced by a neater and more cryptic formula where S for Subject somehow via S

1

(S

n

) is rewritten as O for Object, o

1

, o

2

, o

n

.

Oh.

Or you could simply leap back, either without signalling, or using a phrase like to return to the subject of discourse, to return to our hero, or the old standby of adventure stories: Meanwhile, back at the ranch. Though that’s naive and clumsy, and in a way cheating since you’ve given the reader a certain peculiar pleasure in frustrating his vulgar desire to know what happens, and that pleasure should not be dropped too brutally, leaving him hungry for it. On the other hand the vulgar desire to know should be kept warmly floating in his mind. He must not be allowed to forget the hero or whatever the initial subject was. The two pleasures, the intellectual pleasure in your game, and the curiosity, should be skilfully balanced, you should build in him a sense of trust, so that he feels you know what you’re doing and abandons himself to your wiles. You keep both pleasures going. Do you follow the principle? Yes Barbara?

If the author has lost all authority like you said about the omniscient narrator how can he build up a sense of trust?

A good point, and the subject of our present analysis. But you’re putting it a little too simply perhaps. The author has lost authority many times in the history of narrative, when one type has consumed itself, the element of manipulation becoming too visible thus destroying the fictive illusion, and no-one has yet come along to renew it, usually, as here, reconstructing it by perpetual destruction, generating a text which in effect is a dialogue with all preceding texts, a death and a birth dialectically involved with one another, but this is another problem. We’ll come to that.

Ali Nourennin makes a brief phenomenological analysis of narrative time, bringing in Heidegger, Husserl, and Hegel’s revolution that has been long preparing out of archaic flaws in the dialectic of change, raising antinomies of action that surpasses the subjective idea and renders it objective so that man realises retrospectively that he has accomplished more than he desired and worked at something infinitely beyond him. Are you already practising the art of digression Mr. Nourennin?

So that you could work backwards towards your main subject through other digressions, unless you simply leap back and say but to return to Larissa, though that would be rather clumsy and in a way cheating since you have given many women a certain peculiar pleasure in frustrating their vulgar desire to know what happens inside you, and that pleasure should not be dropped too brutally, leaving them hungry for it. The two pleasures, the pleasure in your game and the curiosity, should be skilfully balanced which is the work of a lifetime. You should have given her a sense of trust, so that she could have abandoned herself to your wiles in keeping both pleasures going. Do you follow the principle? The principle being that you do not follow the principle, you separate yourself from it though you remain good friends and write fairly constantly leaving the door open onto other doors as you drive away into the night twiddling along the transistor and watching the luminous colored hoops dance in the bluish rectangle that reflects the rear before you.

We’ll come to that.

Meanwhile in Philadelphia

Let the shot precede the introduction of the pistol.

And if one settling a pillow by her head should say That is not what I meant at all That is not it at all, fill the air with quotations for the aisle is full of noises where angels fear to tread nel mezzo del cammin because I do not hope to turn again where the lack of imagination had itself to be imagined for a flash for an hour

slipped

out of

the rigid rectangle of time tablet able to preserve the name of the fa bled farther law bearer who unab le to forbear his anger breaks all eleven commandments (10+1) in the textual act and brings new tablet s(Shh) not rEplicas of thE prime uNs

Who is it saying O in the mountain? Putting his foot in it on a Thothday or is it Friday thus introducing a statistically improbable formal order in the general curve of entropy which will however be restablished by the scattering winds, the Noble Savage or the Blue Guitar? See Bibliography*.

*retrogradiens

Wallace Stevens John Dryden Umberto Eco Daniel Defoe Sigmund Freud Moses Ezra Pound Wallace Stevens T.S. Eliot (or Guido Cavalcanti) Dante Alighieri Alexander Pope William Shakespeare Saroja Chaitwantee S. Eliot Snoopy Hegel Ali Nourennin and the occidental discourse of Westerns.

**retroprogradiens

The retrovizor 1001 Nights Ezra Pound Lewis Carroll Robert Burns Lewis Carroll Robert Graves Louis Hjelmslev Ali Nourennin Paul Stradiver oh her Georges Bataille William Shakespeare Jacques Derrida A.J. Greimas Noam Chomsky Plato Ezra Pound the voters Ruth Veronica his reflection Diderot Roland Barthes Edward Fitzgerald Francis Bacon Sophocles W.K. Wimsatt Robert Greene Daniel Defoe Moses Wallace Stevens Sigmund Freud Wallace Stevens the folk Barbra Streisand Jesus Christ Frank Kermode Jacques Lacan Denis Diderot the Institution Ezra Pound the chairman of the hour Jeremy Roland Barthes Francis Bacon Jeremy Armel Tzvetan Todorov e.e. cummings the short plump demagogue Bertrans de Born James Joyce Wayne C. Booth Homer Roman Jakobson Julia Kristeva Ali Nourennin et al W.B. Yeats Northrup Frye Umberto Eco John Cage Jane Austen a Victorian old maid Julia Kristeva Dr Santores the Institution Saroja Chaitwantee Traditional wisdom Gertrude Stein William Shakespeare Peter Brandt Christopher Isherwood Ali Nourennin Anton Chekov the chairman of the hour hagiography Armel? the lanky henchman Julian Claire Oliver the chairman of the hour Charles et al Homo Scholasticus Laurence Sterne Choto Rustaveli Scheherezade Tzvetan Todorov the Student Body Karl Marx Plato Tristram Shandy Alessandro Manzoni thus meeting up with the occidental discourse of the Western.

Who is it?

Hello, Ruth?

Armel! Hi.

Hi.

Er And to what do I owe the pleasure?

You haven’t had it yet. You free right now?

Honey you all right?

Sure why?

First time you’ve rung to say that usually it’s me.

Well there’s a first and last time for everything.

What, what do you mean Armel?

You alone?

Yes.

Send him packing I’m coming right over.

Armel that’s not fair you never no never two nights running but never regular nights either so she never knows where she stands I never know where I stand what do you mean stand on this rather hastily remade bed I guess it’s difficult to lie, naked, even on the phone with a naked man beside you.