The Brooke-Rose Omnibus (82 page)

Read The Brooke-Rose Omnibus Online

Authors: Christine Brooke-Rose

Or at any rate, it needs adjusting.

Her hair is fair or dark, it doesn’t matter except in gothic romanesque now that there are such subtle dyes even within the text. She is pale and sits

Where?

On the campus

Can one sit on a campus?

She sits on a castle terrace in Spain.

Caramba not picaresque that’s as dead as the dread-letter novel.

In Slovenia, talking to the count

Titles have been abolished in Slovenia

turning her back to you. It is a warm summer evening. The benches and tables are of wood, under a trellis of vine, facing the crenellated walls that hide the view of the valley. Scrub that. The bench and tables are of wrought iron, under the palladian colonnade, facing the flight of white stone steps that lead to the wide gardens wrought-ironed beneath the moon in patterns of clipped privet. By the light of adapted eighteenth-century

coach-lamps

between each tall french window two foursomes call out one heart, I pass, two diamonds, three clubs, three diamonds, I pass, four diamonds counterpointed by three hearts, four clubs, four hearts I pass. Other groups sit and talk, smoking and sipping wine.

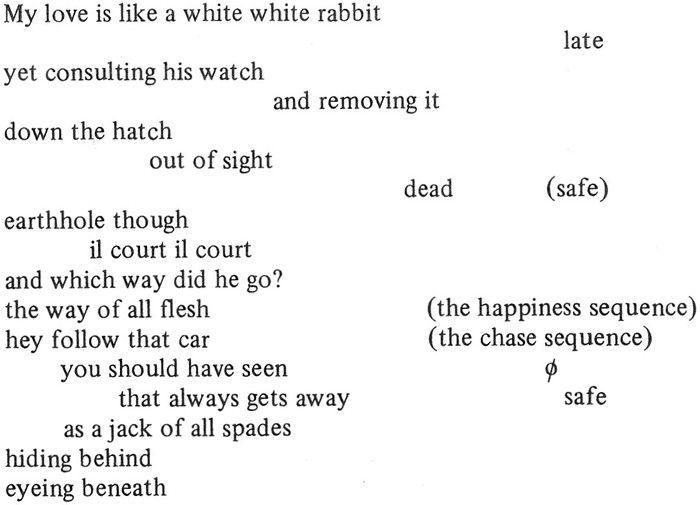

The count is a mad mathematician who makes strange signs on a sheet of paper as she leans half facing him, right breast tensed out by the angle of her arm right hand on her right hip, her thighs crossed tight under a black silk skirt, left elbow on the table the left hand supporting the long curve of jaw with thumb under the chin and the two long forefingers up into her temple hair the other two below her open lips, the two sets of two fingers forming an angle for the deeply interested gaze upon his words and symbols, and at the angle the wedding ring and the sapphire delicately ovaled in diamonds. But you should know Boolean algebra dear lady it would help you considerably look, I simplify, the connectives are not, or, and, if.

You feel so totally out of it that you will spare the other recipient the details since you are only a substitute narrator, jack-in-the-box not jack-of-all-trades, a mere pistol whose only role is to utter by chance or by sudden overwhelming desire the words of love for ever unbelieved. We’ll come to that. The details over his handsome shoulder a little too close to hers look like a rectangle crossed by a diagonal marked with capital letters, followed by another set of letters the last line of which he says is a false premise with a true implication. The false premise being apparently that she has asked him how to represent in two dimensions a

three-dimensional

graph of narrated time past present and future, coding in as well narrative time for the reader as an unknown variable, the writer’s time being irrelevant since the author does not exist, she says, only the text. And the true implication being perhaps her retrospective realisation that she has worked at something infinitely beyond her and beyond you too, so that you want to break up this communion of false premises with your uncomplicated desire which has been quietly generated for some time out of your request for a lift from her ebullient presence and black Fiat Luxe to Hungary where Marika lives on whom you last put terrific pressure to leave her husband escape to freedom and you and whom you itch to see whether. You’re mad it’s miles out of my way Oh please it would be such fun And then what you dump me in Budapest? Well er no of course So what then will she like seeing you arrive with another woman? Think pig. Why pig? It was a quotation, from Beckett. Who’s Beckett? Two clubs, two hearts, two spades.

Leading metonymically via your desarroi and desire and the hot summer evening to the dutch courage from the slovene wine which enables you to down your shyness and break up the communion of false premises with another in close hot urgency near her perfumed ear when are you going to stop this and pay attention to me I can’t compete I’m not the latin lover type.

She laughs. I’ll deal with you later.

And no doubt she does.

Meanwhile something has gone wrong with the narration owing to textual disturbances. The castle seemed momentarily to be French. And yet you have drunk slovene wine and referred to the count as the latin lover type, the French being Frankished Gauls, despite the fact that you are yourself Italian, obviously with a name like Marco. Unless you are Stavro after all in which case you could be Albanian. Or Russian or maybe Slovenian. The Albanians could have been Etruscans.

Perhaps you had better transfer the whole scene to Mexico.

They don’t have counts in Mexico, or castles.

Or to California which is full of exiles and where they move castles from Europe stone by stone or construct fake follies. So you could move it too, No, better in Europe where the revolution will not occur since

Oh keep that out of it we’re on vacation now not on campus. The students have dispersed and the continuous notation cards on which you compose portraits and double portraits have been cybernetically processed into degrees of absence, permutated through the computer into grades obtained for this or that course the chaotic freedom in the choice of which makes you drive off onto the highway towards the paradiso terrestre. This is an idyll. Who speaks? There is a confusion of voices here, out of narrative time and out of character. The highway moreover is not always high, and in some cities the thruway goes round.

It is the Count who speaks however, pressing her into reading

I

promessi

sposi

as the best novel in the world and who is therefore quite evidently Italian, even if he is not a count.

But why a castle? It cannot be merely to change the scene since motivation is a cost and V = F. It could be a hotel (for realism). It could be for alliteration: a castle in California? in Catalunia? Calabria? Caledonia Canada Karinthia Kamchatka. But the punishment in final position has occurred on the diasporic term: the castle must be in France (Cantal or Aquitaine). Cancel however the calls of bridge. It is a Congress in Semiotics and semioticians do not play bridge but at semic polarities.

Or on a pale guitar addressing herself for you as La belle si tu voulais (bis) nous dormirions ensemble o-la (bis) and answering you with No vale la pena el llanto and readdressing herself for you with Yo no te offresco riqueza, Ti of fresco mi corazón and reanswering you with You ain’t going nowhere and a strange gaze at you through the whole repertoire in the dialectic of desire that gravitationally pulls you towards the centre of attention she enjoys as from the start an object of central loss, the sheer questiontagmatics having reversed the subject into a foreknowledge of the whole repeat performance which can only belong either to the narrator as a cheating young god or to Larissa as a well established structure that presupposes a void a fall into a delirious discourse watched indifferently through fingernail parings.

I’m not very good the first time.

O for a beaker full of the warm southern night that generates the first time into n swiftly changing viewpoints floating up from deep level dreamlessness every n minutes or so for a shared murmur of sweet nothingnesses then down again as mouth removes to mouth female to phallus in the show within the show, sucking the performer dry with recursivity from left to right in a performance that is to his competence as his nose is to his brow.

Fear is the function of his narrative.

You know his fear falls on the initial position but also on the last, he being a dysphoric term beneath his youphoria. And that the end of the kernel sentence is proepigrammed by the beginning, not by the bold centrecodpiece in mid copula as a wild manner of speaking pistolshot words like will you stay with me always always please will you marry me.

always? always Death said

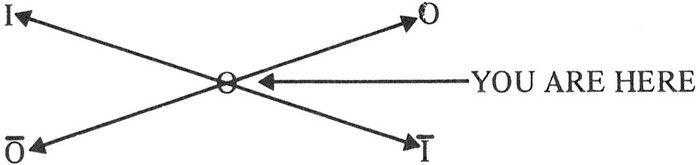

The introduction, into the superficial grammar, of wanting as a modality, permits the construction of modal utterances with two actants united in a proposition, the axis of desire then authorising a semenic interpretation of them as virtual performer subject and an object instituted as value. Adam wants an apple Adam wants to be good. Such an acquisition, by the subject of the object, seems to occur as a reflex action, which is only a particular case of a much more general structure well known as the diagram of communication represented in its canonic form as an M and a Y of crossed limbs with diagonals from the I to the object

never believing anything said in moments of passion

(the notion of which has disappeared)

But I meant it, please, will you?

No my love, love is just a four-letter word.

That’s only a song, you know it’s more than that.

And when we’ve read the letters inside out and upside down you will go forth, and multiply.

But I don’t want to multiply I have three children already.

Go forth then. Fort-da.

What do you mean fortda?

Oh nothing. Just ticking myself off with something Freud said.

Da means yes in Russian

and gives in Italian so what? (Yes is for young men)

Or if by such misassociation when waking by anyone who swears eternal love make love not war make conversation as if conversation could be made all horizontal coordination degenerating into useless chatter: I didn’t know you were married.

I’m not I refused to marry her she took my name by Deed Poll.

Marriage is an outmoded institution. Only a few priests are thinking of it.

But you’re married.

Yes. What’s her name?

Maddy.

What?

Maddy. Well Madeleine really. Out of which improper name pours the surface grammar of his narrative disturbances for hours and days you shouldn’t talk of her like that you must have loved her long enough to have three children by her only two one is by an early marriage in Italy now annulled I didn’t love her you don’t know her she’s awful she drinks she’s a lousy mother she neglects the children it’s awful and I left her the house the car she’s done very well out of me. But I love my children I’m worried stiff about them it’s bad enough that I’ve become just a sort of uncle to Enzo that’s the first one but well as an unmarried mother she has all the rights I’m only the absent father. But I want to take them away from her oh please help me. Now, soon, I need you.

But when the shoulders shift back to the correct position the cars that look grey eminent into the retrovizor do not look double-faced or quadruple-eyed out of focus together with the four eyes but untarnished with single grins between two pale gold eyes one on either side or else two smaller city substitutes lower down but never two pairs together.

the grey eminence the retro-vizir beyond the consultana haggler of head nouns chopped below the performance yes your eminence I’ll come to that your reference but meanwhile

the retrovizor has a bluish tinge in the cold light the rectangle turns smoky grey to dim the dazzle of floods undipped or even gently dipped but the glare is preferable to the sudden isolation of almost not seeing behind a head

the dancing hoops. For the gold eyes when distant turn into hoops (at night in the correct position) of luminous green red amber bouncing in out of through and through each other narrowing to slim ovals vertical horizontal swaying undoing swiftly changing viewpoints as if juggled by a

magician

or the black recumbent street below and with the

overhead

bridges that make perhaps the optical illusion.He shifts the mirror to his rearward glance. It doesn’t appear to work for him the lover of the moment of sudden isolation at not seeing the black magician who tantalisingly juggles luminous hoops into the rectangular hey you put my mirror back.

So it needs adjusting.

Why at this precise point introduce another idyll? Intensity of illusion is what matters to whoever is operating through a flaw in the glass darkly perhaps making two or four clear eyes stare back, two of them in their proper place at height of bridge of nose and, further up the brow, theother two, exact replicas but dimmed as in a tarnished reflection, tarnished by the fringe they seem to peer through. A

second pair of eyes hidden higher up the brow certainly has its uses despite psychic invisibility or maybe because of. Gazing they do not see themselves. They reflect absolutely nothing, nor do they look at their bright replicas below in the proper place on either side of the nose which is a fraction iconic according to Armel but not precisely in this instance. Only these lower eyes, reflecting, presumably, the eyes of the real face as it leans for reassurance a bit to the right, see the upper eyes, looking up at the fringe of straight brown hair.

and so you glance askance at the short thick muscular body nevertheless a young god yet as you plunge into the dimension of his banality with the intention of tran-

smogrifying it by utterance into an idyll. Or a blue lacuna of learning moon june soon a blue lagoon.

Oh?

No well let’s face it, so far, as an idyll, it’s a flop.