The Brooke-Rose Omnibus (77 page)

Read The Brooke-Rose Omnibus Online

Authors: Christine Brooke-Rose

So far however there are no actant-places except the other scene and the institution of learning where the old learn from the young and the young learn precious little until suddenly one day they too are old.

We’ll come to that.

Meanwhile, back at the other scene.

Armel works on the idyll. Or rather on the bucolic pastoral as opposed to the rustic.

The invariants found are

1) the place, which becomes no longer Arcadia as in the classical pastoral but simply the anti-town, the hills, the country.

2) the rustic love-song manifest through fixed motifs such as the boastfulness of the shepherd, the burst of anger with invectives the exchange of gifts and the comparisons taken from rustic life to comment the girl’s beauty.

3) an equivocal use of pastoral and agricultural terms for sexual ends.

4) the display of visceral organs overflowing from excess of amorous anguish.

Having laid out the alleys and determined the streets, we have next to treat of the choice of building sites for temples, the forum, and all other public places, with a view to general convenience and utility. If the city is on the sea, we should choose ground close to the harbour as the place where the forum is to be built; but if inland, in the middle of the town. For the temples, the sites for those of the gods under whose particular protection the state is thought to rest and for Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, should be on the very highest point commanding a view of the greater part of the city. Mercury should be in the forum, or, like Isis and Serapis, in the emporium: Apollo and Father Bacchus near the theatre: Hercules at the circus in communities which have no gymnasia nor amphitheatres; Mars outside the city but at the training ground, and so Venus, but at the harbour. It is moreover shown by the Etruscan diviners in treatises on their science that the fanes of Venus, Vulcan, and Mars should be situated outside the walls, in order that the young men and married women may not become habituated in the city to the temptations incident to the worship of Venus, and that buildings may be free from the terror of fires through the religious rites and sacrifices which call the power of Vulcan beyond the walls. As for Mars, when that divinity is enshrined outside the walls, the citizens will never take up arms against each other, and he will defend the city from its enemies and save it from danger in war.

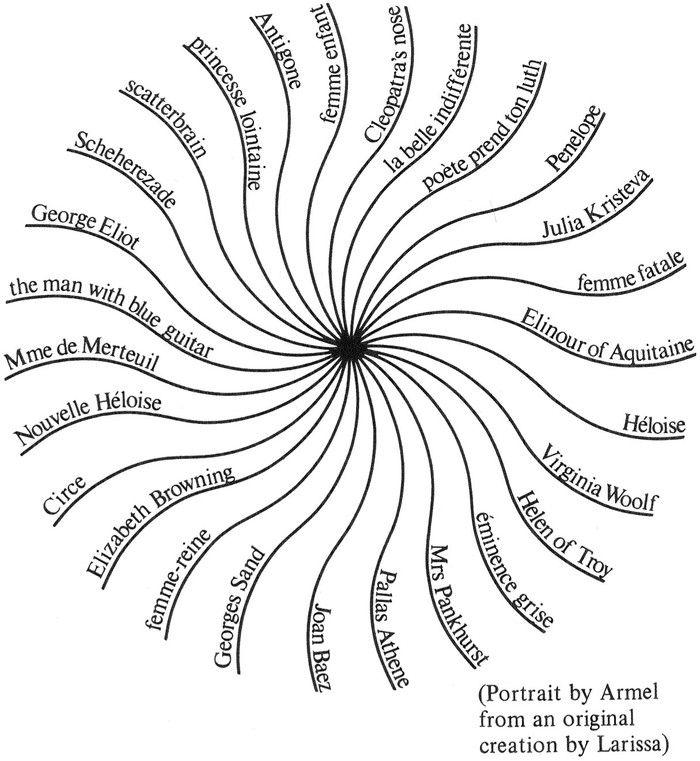

(Portrait of the town and

antitown by Vitruvius)

And if it is written up there by the narrator(s) that the shepherd shall boast in the antitown with mercurial exchange of gifts and display visceral organs then so it shall occur even though the narrator(s) may withdraw at last into the proepigrammed

arbitrariness

of a vacation, paring their fingernails. At which point the shepherdess’s adoration would necessarily be tempered with a new anguish at the shepherd’s obstinate refusal either to marry her or to live with her in an unpastoral pastiche of marriage (as he puts it, firmly keeping the fane of Venus outside the body politic), an anguish that might veer into jealousy or is it outrage as to what prevents him, given all that adoration given, however, only as a terminal string of symbols or object of exchange in a rewrite derivation where the object is raised to become subject of adoration which has to occur before the passive transformation into a sort of bird flying around the room unable to get out. For although the mise-en-abîme is eternally a mise-en-scène, syndiachronically orgyanised into a spacetimetable of yes your reference I’m coming to that erogenous zone in the sixth hour which is the work of a lifetime enclosed and isolated in a Silling Castle behind great bridgeless canyons, there is no promotion from object to orgyaniser no liberty for the victim of the libertine despite the undoubted fact that within the grammar of that narrative the roles can be interchanged and textasy multiplied until punctually at a fixed hour all the forged orgy ceases. For the deep structure of I am your slave is undoubtedly you will be mine and yet there is no transformational rule in any grammar which explicitly effects this since it is written up there that all deletions, reflexivisations dative movements object-raisings and other transformations be recoverable so that here it is merely a question of conjugality which comes under the lexicon and the morphophonemic rules as for example in please don’t go Armel it’s so nice having breakfast together.

I must go.

But why my love. We’re alone. Christopher has gone, Larissa has gone. You’re going back to an empty flat.

Precisely.

I don’t understand.

You do really.

Perhaps I do. No man can hide a secret even in silence, he will chatter with the dropped parings of his fingernails.

Let’s enjoy it while we can my love, don’t let’s spoil it, it’s beautiful.

But that’s just why it should last why are you so pessimistic?

What were you dreaming just now do you remember?

No, was I asleep?

Yes, you were muttering.

I wish you’d talk to me Armel.

But I do talk to you.

You know what I mean. Yes, we talk, of things, art and literature and God and dreams and beautiful landscapes and we laugh a lot and I’m very happy then. But you never tell me things, real things. You for instance. What do you really want?

My tie, where’s it gone?

There. How long, Armel, how long?

That’s what David said.

Who’s David?

The psalmist. In Paris, where I lived for some time, the telephone is overloaded, and on international calls one tends to get a recorded voice saying Votre demande ne peut aboutir. Veuillez appeler ultérieurement.

And will, somebody, tell me, why, people, let go.

The shot can precede the introduction of the pistol.

I was quoting Cummings. I like him so much better than Christopher’s nature stuff. You opened him up to me Armel and so much else besides and now you don’t recognise him.

I did, but why wave quotation marks. I answered with another quotation.

From what?

I forget. Some essay.

Like all your answers it wasn’t an answer.

Don’t always ask the same question then, Veronica.

I’m sorry.

It’s all right. I’m going now. Sleep well my love, have interesting dreams.

Larissa’s in Paris isn’t she?

No.

Where is she?

I don’t know.

You must know.

Stop pressuring me, I’ve asked you before. I refuse to discuss her with you or you with her.

The adulterer’s cliché. Oh Armel don’t get angry I’m sorry. I can’t stand that terrible glare in your eyes when you get angry you look so different. Forgive me. I just get, very unhappy sometimes I mean I know you made no promises you were quite honest but we didn’t know we’d fall so deeply in love that I, would, really, fall so, deeply, in love oh Armel.

Come my little one, my little girl. There. My beautiful one my Venus. Don’t cry. Aphrodite never cries.

But couldn’t she be happy with you in the orbit of an eye and no reference without? Never let anyone see you see through them therefore

Never let yourself be fully known

Give not your soul unto a woman and yet

There is no fear in love

To adore is to give your soul but: Eurilochus?

Fear is the function of his narrative.

Oh another one who grabbed a balloon and then let go.

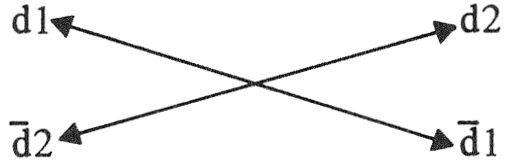

These are adagia that function as functions at the level of performance not competence. It is not clear who speaks last, a friend of Veronica’s perhaps or more likely of Larissa’s, the cases being caught up in the eternal quadrangle or, if you prefer it, which this friend clearly does, two deixes that are conjoined, because

corresponding

to the same axis of contradiction, but not conforming, and equivalent, at the fundamental level, to contradictory terms:

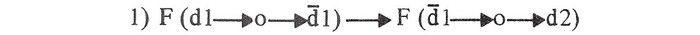

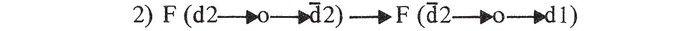

Thus the circulation of values, interpreted as a sequence of transfers of value-objects, can have two courses:

which, in the case of the Russian fairy-tales of Propp, can be interpreted: society (d1) experiences alack, the traitor ( 1) ravishes the king’s daughter (o) and to hide her transfers her elsewhere (d2).

1) ravishes the king’s daughter (o) and to hide her transfers her elsewhere (d2).

which means: the hero ( 2) finds somewhere (d2) the king’s daughter (o) and returns her to her parents (d1).

2) finds somewhere (d2) the king’s daughter (o) and returns her to her parents (d1).