The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (49 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

Until that day, here we are, trapped in our own personal history, which in turn is nested in human history, and that in turn is embedded in biological, evolutionary, geological, and cosmological history. Beyond the personal level, history won’t end today, or tomorrow, or on a date in late December 2012. The timewave’s point of “maximal” novelty is destined to come and go—as for many readers, surely, it already has—reduced to one of those quirky wrap-up pieces delivered on the nightly news. There will be no celestial chariots or mile-wide ships, no massive asteroid impact or volcanic eruption, no gamma-ray burst from a distant supernova that wipes out ninety-nine percent of earthly life. Such events could happen, I suppose, but I don’t believe they can be predicted. With the rare exceptions of global natural catastrophes that occur every few million years, novelty works more locally and slowly than these scenarios would have us believe.

Whatever the predicted end date, we’ll wake up the next day facing the same intractable woes we faced the day before. Rather than confront those challenges, however, many of us will choose to focus our hope and dread on a new zero point ahead, longing for some resolution to our dilemma, some final outcome no matter how catastrophic. Strange, perhaps, but we are a species so adept at denial that even a vision of the apocalypse is a welcome distraction from the thought of devoting ourselves to making the time we are afforded the best it can possibly be.

I’ve been hard here on Terence’s concept from a scientific perspective, partly because he spoke of it in scientific terms, imagined it could be calibrated with scientific precision, and invited scientific minds to critique it. That said, I’m keenly aware that the timewave has a value and beauty that lies outside the grasp of science. Does it describe the structure of time itself, as Terence postulated? I doubt it. But in the tantalizing way of astrological correspondences and the

I Ching

itself, the timewave does seem to describe

something

about the world, something significant and yet impossible to define. The element of subjectivity is so intrinsic to interpreting these constructs that one can read into them whatever one wants to find. Somehow, paradoxically, that suggests both their fatal flaw and their mysterious power as mirrors of the hidden self.

There’s yet another way of looking at the timewave, I realize—one in which its predicted end time is already upon us. The rate of change in global events, environmental decline, and technological advance gives every sign of speeding up. Even as things seem to be falling apart faster than ever, there are developments that could lead the era through the historical bottleneck that appears to loom just ahead. It is a race between the forces of entropy and chaos and those of order, evolution, and progress.

Come to think of it, maybe that has always been so; perhaps our age is not as unique as we might like to believe. It’s very hard to discern the nature of the present, let alone to envision the future. Terence’s gift may not have been the ability to predict what events would undergo the formality of actually occurring, but to understand before most of us which ones already had.

Chapter 37 - To See the Great Man

Once Terence and I had finished the manuscript for

The Invisible Landscape

in the early fall of 1974, we drifted apart again. After a year in the Bay Area, I was tired of my restaurant job and craving an adventure, away from Terence and his influence. On some level, I think, he was still concerned about my stability, as yet not fully trusting me not to spin off again into madness or delusion. He was playing dual roles as elder brother and, in some respects, as father. His concerns were sincere, but I had to push back. I was also beginning to think about what I should do with my life. Eager to get out of Berkeley, I hatched a plan.

In those days, Greyhound offered a bus ticket for sixty dollars, I believe, that let you travel for sixty days anywhere along their routes in the United States and Canada. It was a great way to see the country, provided you could stand that much bus riding. Having saved some money from my restaurant work, I took that and some of my book advance and headed out.

My ultimate intention was “to see the great man” as the

I Ching

would have it—that is, to approach a figure with the wisdom and authority to change my life. In seeking out the master, the student isn’t waiting for novelty to make its entrance, but inviting and even taunting it to do so. The benefits can be tremendous, but there is always an implicit danger as well. I hadn’t forgotten my brother’s encounter with Gunther Stent.

In my case, the great man was Richard Evans Schultes, the famous ethnobotanist at Harvard, director of its Botanical Museum and the world’s expert on hallucinogenic plants. As I mentioned, it was his leaflet on “

Virola

as an Orally Administered Hallucinogen,” that had lured us to La Chorrera, looking for the obscure Witoto hallucinogen

oo-koo-hé

. La Chorrera was the ancestral home of the Witotos, and Schultes had made important collections there. In addition to meeting Schultes, I wanted to ask him if there might be a chance I could pursue graduate studies under him.

My roundabout route began with a detour for visionary purposes. In the three and a half years since my return from La Chorrera, I’d almost entirely avoided psychedelics. I had one experience with peyote that went well and revealed no signs of a lurking proclivity to psychosis. I felt it was time to reconnect with the mushroom mind. By then it was known that

Psilocybe cubensis

was not only abundant in South America but also fairly common throughout the southern United States, found just about anywhere there were cattle and pastures. As it happened, some former acquaintances in Boulder had recently moved to Hammond, Louisiana and opened a hippie leather and crafts shop. They had rented a little house outside of town near a pasture that should have been prime mushroom habitat. Assured there would be mushrooms and a place to stay, I headed to Hammond. That fall had been dry and the crop was sparse, but I found enough to ingest several times, and that proved a good reintroduction to my fungal friends. The shrooms there were much weaker than those at La Chorrera, which was a lucky accident; the gentle trips were a good way to ease back into that dimension.

After a week or so in Hammond, I rode on to Richmond, Virginia, where I visited a linguist who at the time was perhaps the only non-native speaker of Yanomaman, the language spoken by the Yanomami peoples of the Amazon along the Venuezuelan-Brazilian border. In our correspondence, he told me he had several samples of

epená

, the DMT-containing

Virola

snuff used by the Yanomami. I was more interested in the drug than the people, unfortunately, but my host generously shared his collections. Years later, I was able to include them in the analytical work on

Virola

that I carried out as part of my doctoral thesis work.

From there I headed for Boston and my meeting with Schultes. I arrived in Cambridge on a sweltering afternoon and went immediately to Harvard Square and the Botanical Museum. I cleared the receptionist in the lobby and was ushered upstairs to the office of the great man himself.

The door was ajar, the shades within closed against the afternoon glare. Peering into the gloom I couldn’t see anyone at first. Then my eyes adjusted and I caught sight of him toward the back of the room. Clad in a white lab coat, he was literally hugging an air conditioner in one of the windows! It was most incongruous to see this swashbuckling, legendary figure, now portly and middle-aged, snuggled up to his air conditioner. The afternoon was terribly hot in the way that only late Indian summer days can be, and I hardly blamed him. I was charmed, in fact, to see this display of vulnerability. Apparently even the great jungle botanist enjoyed his creature comforts when he had them.

Noticing me, he came forward and introduced himself. We had corresponded so my visit was more or less expected, but we hadn’t set a time. Schultes was everything I had hoped he would be; he was completely charming and kind, every bit the fatherly mentor. How many other bearded, bedraggled hippies had made this pilgrimage? I was surely one in a long line. For anyone with my level of interest in hallucinogenic plants, Schultes was a luminary, and meeting him was an unparalleled honor. I was disheveled and sweaty from my walk from the bus station. I had been on the bus for days and probably smelled like it, but if that bothered him he didn’t let on. Having greeted me as a colleague and equal, he shut up his office and took me to dinner at the Harvard Faculty Club.

Along with his pioneering collections in the Amazon, Schultes was known for the diverse and talented cadre of students he attracted. One of them was Wade Davis, today a well-known ethnobotanist, writer, and “explorer-in-residence” at the National Geographic Society. While I was chatting with the professor in his office, Davis was traveling in South America with Tim Plowman, another Schultes protégé, researching coca, the plant from which cocaine is derived. Davis would later write about their long journey in

One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest

(1996), a book that features affectionate portraits of Plowman, a brilliant ethnobotanist destined to die young, and the mentor they shared in Schultes. As Davis notes of the latter, “At any one time he had students flung all across Latin America seeking new fruits from the forest, obscure oil palms from the swamps of the Orinoco, rare tuber crops from the high Andes.” Schultes had a remarkable influence on the young people who, in his later years, became his eyes and legs in the field. As Davis observes of Schultes’s letters, “It was impossible to read them without hearing his resonant voice, without feeling a surge of confidence and purpose, often strangely at odds with the esoteric character of the immediate assignments.”

I felt something like that in his presence at Harvard. We spent the afternoon discussing our mutual interests, and my ambition to study under him and perhaps further investigate

Virola

. My spotty academic record came up; I had taken some basic botany courses, plant morphology, and taxonomy of the angiosperms, but practically no chemistry. He advised me I needed to get organic chemistry under my belt, and maybe more taxonomy, in order to qualify for admission to graduate school. If I could do that, he said, he thought I could probably be accepted, and he assured me he’d try to facilitate my application. I left the meeting fired with ambition, utterly stoked and ready to do whatever it took to work with him.

My friend Beverly and I spent time together over the next few days touring the city’s museums and art galleries. It was a great reunion, a renewal of our friendship after its rocky chapter in Boulder. I got back on the bus and stopped in Ann Arbor for a day to rest and check out some bookstores, then headed for Vancouver. Though bus travel could be grueling, I had a secret that made it not only tolerable but pleasant: a stash of hashish-tobacco cigarettes I’d pre-rolled and disguised to look like ordinary cigarettes. The buses were never crowded, so it was easy to stake out a couple of seats toward the back. I’d bide my time until well after midnight when most of the passengers were asleep and then discretely light up. The ventilation system wafted away the smoke, which smelled mostly like tobacco in any case. Or so I told myself, enjoying my thoughts, and my visions of a new future as the bus cruised through the velvet darkness after midnight.

I arrived in Vancouver just in time for a Grateful Dead concert, stayed with friends for a few days, and then made it to Berkeley in time for Thanksgiving. But that was just another stop along the way. Schultes had helped me define a mission. I was bound for Colorado and determined to get back in school.

My plan was to live in Boulder, but I ended up at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, where a friend had a job tending the horticulture greenhouse. I found an apartment in the building where he lived and registered for the next semester. I took two classes: one in “grass systematics,” a taxonomy course that had me struggling a bit with the arcane keys used to identify various species; the other in introductory organic chemistry, which I loved. The professor of the second, Frank Stermitz, turned out to be a natural products chemist specializing in alkaloids and a gifted teacher. I remember him illustrating a lecture with a look at LSD, comparing synthetic production to the biosynthetic route in the ergot fungus. Needless to say, I was rapt.

Chapter 38 - Fun with Fungi: 1975

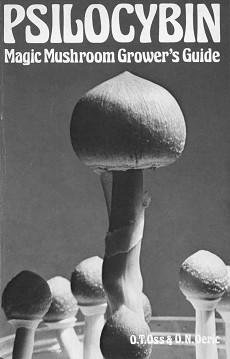

Cover of the

Grower’s Guide

, first edition, 1976. (Photo by J. Bigwood)

The move back to Fort Collins was a first step in the new direction I had embarked on after my pilgrimage to see Schultes. I had separated, again, from a life near Terence and begun charting a new career. But my brother and I still had an important bit of business inspired by the Teacher we’d yet to finish: figuring out how to cultivate the mushrooms. We wanted to have a steady supply so we could easily revisit those dimensions; more importantly, we wanted others to have their own experiences as a way of testing ours. At La Chorrera, we had collected spore prints from the mushrooms. Later, in Boulder, we made efforts to germinate the spores and grow mycelia on petri plates. We didn’t know what we were doing and had little success, but we hadn’t given up.