The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (46 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

Science, to its credit, abjures faith and demands that any scientific model of reality be backed by evidence. Science does an excellent job of studying phenomena in isolation and in great detail; but it does a poor job of fitting all those small, dissected pieces of reality together into a unified whole that hangs together, and that seems to fit our holistic experience of being. The reductionist scientific models are impoverished and unsatisfying; they leave more unexplained than they explain, and they, too, seem unable to account for the improbable situation in which we find ourselves.

And highly improbable it is indeed. Think about it: We are a conscious, minded species that somehow arose on a minor planet circling a G star in some backwater of the Milky Way. We have invented language and, proceeding from that, science, technology, religion, art, war, and all the other accoutrements of civilization. We have no idea whether we are unique in the universe, but there’s no reason to think so. In line with the ideas of Jean-Pierre Rospars and many others, life evolves in accordance with certain “rules” of evolution; wherever the conditions are favorable, life will arise, and once it has arisen, it’s likely that it will achieve intelligence. There’s no reason to think it has not happened dozens, hundreds, or millions of time in the history of the universe. But we have no proof that it has; it’s only a reasonable assumption at this point, a working hypothesis if you will.

And then “the mushroom” or whatever/whoever the mushroom represents, comes along and matter-of-factly tells us how the boar ate the cabbage—how things really are. We are an immature species involved in a symbiosis with a much older and wiser mentor species; this species is trying to get us to wise up so that we can join the galactic community of minds, and do so before we manage to blow up the planet and ourselves. It’s probably a scenario that has been repeated many times in the history of the galaxy. It is a comforting myth, at least, and we can choose to believe it, or not. Is there evidence for it? The closest thing to that so far is a shared interpretation of what the mushroom seems to be telling us, as reported by a growing number of people who have experienced psilocybin firsthand.

That is not “hard” evidence, but it is evidence of a sort. And it does not require faith, unlike religious myths, which do. No one is asking you to abdicate your critical faculties. The mushroom, or whatever that term stands for, demands the exact opposite; it demands that we reject faith. All we need is the courage to experience the phenomenon and judge it for ourselves. Those who take this empirical, scientific view are apt to be presented with a model that is plausible, or is at least not impossible, a model that suggests there just may be such a thing as human destiny—and that our existence, as individuals and as a species, may have meaning after all.

Part Three - Invisible Landscapes

Chapter 35 - Invisible Landscapes

By early summer 1971, I was living in a tiny room in Boulder and trying to reinvent the poor student I’d been before I left. I busied myself in summer school and found a job as a dishwasher and server in a rest home. It wasn’t the most edifying work, but I took pleasure in the normality of it. I was still dealing with the memories of our experiences in the jungle, but I had no one to talk to about them, least of all the pure-minded, fair-haired Peggy, my longed-for, if mostly imaginary, flame. In a brief encounter with her, I tried to explain a bit about what had happened to me, but it was useless. Her reaction was one of alarm, and no wonder, with me raving like a wild-eyed prophet back from his forty days in the wilderness. She didn’t know what to make of my account beyond not wanting to hear any more of it. She gently broke it to me that she had a new boyfriend, but I hardly took notice, being so caught up in my own drama.

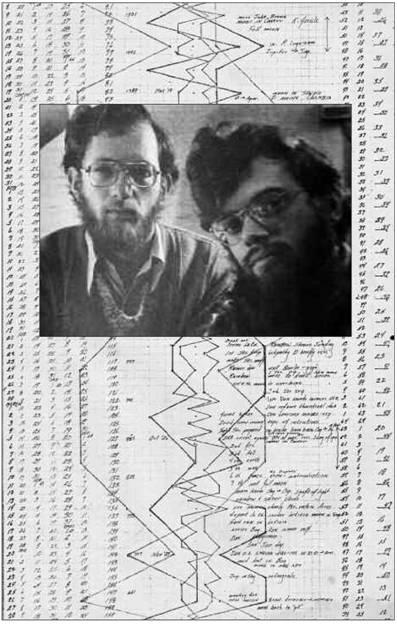

Terence, meanwhile, had spent the previous months in Berkeley, utterly absorbed in adapting his idea for a model of time to the inner machinery of the

I Ching

. As I noted earlier, the

I Ching

consists of sixty-four hexagrams, each corresponding to a different phase in a cyclical, Taoist model of time. Based on that, Terence had, by then, assigned the numbers six and sixty-four a special significance in his calculations. In

True Hallucinations

, he writes that he realized his relationship with Ev began sixty-four days after our mother’s death. Counting forward from our mother’s death by six such units, or 384 days, he discovered a thirteen-month lunar year that would end on his upcoming birthday, November 16, 1971. These were the initial correspondences that got Terence thinking about applying the

I Ching

to his timewave theory. Indeed, his birthday became the first of his projected end dates for the so-called concrescence—the final event the timewave seemed to predict.

Then as before, Terence’s obsessive writing and charting seemed to be part of a reintegration he’d begun after the bizarre events in March. Early on, the numerical constructs he’d apparently downloaded from the Teacher had been keyed to our personal and familial history. He’d continue to refine the timewave concept for years, pushing it beyond its narrow confines toward something wider and more intricate, even elegant, in its peculiar, numerological way. He came to believe that the cycles within cycles he detected on a personal level were active on a historical, geological, and cosmological scale. Terence would later use the term “fractal time” to characterize these nested cycles, though when he first began his investigation the term

fractal

had yet to be coined.

There is also the curious relationship between the

I Ching

and the structure of DNA—that is, the “language” that DNA utilizes to code for the proteins that exist in all living things. I’ve alluded to this earlier. Indeed, talk of this coincidence was in the air at the time. Since the mid-fifties, there had been a growing popular interest in the ancient Chinese classic and in the double-helix structure of the DNA molecule as well. The number of hexagrams in the

I Ching

can be written as 2

6

, or the number of 6-line hexagrams that can be made from lines that can appear in either “broken” or “unbroken” form. In DNA, the number of 3-letter codons that can be generated from 4 nucleotides can be written as 4

3

. The product in both cases: 64. That seemed to resonate with our belief at La Chorrera that we’d somehow hacked into the central store of knowledge that life had acquired and carried over time on a molecular level.

Among the first to note the resonance between DNA and the

I Ching

was one Gunther Stent, a German-born professor of molecular biology at the University of California in Berkeley. Stent explored the idea in his book

The Coming of the Golden Age

, which appeared in 1969. Terence actually visited Stent on campus, eager to share the insights from La Chorrera. Terence’s account of the put-down that followed is one of the more comical and painful moments in

True Hallucinations

. The encounter was not unlike mine with Peggy, in a sense. Each of us had tried to express the ineffable to someone we hoped would understand, only to confront a reflection of ourselves raving like lunatics. I was lucky in that mine occurred with a friend on the street. For Terence, the rebuff from one of the era’s leading biologists revealed something of his ambivalence about science. He loved scientific concepts and language, both of which he was known to borrow for his own playful and metaphoric purposes. He knew the lessons of La Chorrera involved an intuitive leap over an abyss that science in its current state was unable to bridge. And yet he may have wanted the scientist to acknowledge an insight that couldn’t be verified in scientific terms. He had asked one of the leading scientists of his day to endorse what was, in essence, a deconstruction of science, even a rejection of it, with humiliating results.

That’s not to say his only doubters at the time were mainstream academics. During that spring and early summer, Terence’s efforts continued to baffle most of his friends; despite his inborn persuasiveness, he had yet to win them over. In addition, rumor had it that the FBI had gotten wind of his illegal return to the country, arousing his fear that the net cast after the 1969 hash bust might be closing. Both factors played into a decision by Terence and Ev to embark on what struck me, at least, as unthinkable: a return to La Chorrera.

Overall, the rationale for that second trip seemed less than entirely rational. One unspoken motivation, I think, was nostalgia—a yearning for paradise that motivates humans to envision, and seek, magical realms beyond space and time, an impulse that may go back to when our womb-born species first began seeing itself as a creature fallen from an original state of grace. La Chorrera might have made for an unlikely Shangri-La, but there was no doubt that in our imagination it had taken on this numinous aspect.

While Terence felt compelled to go back, I had excellent reasons not to, as I made clear in our talks. He thought we should try to repeat the experiment, even as he paradoxically insisted that, according to the Teacher, we’d already succeeded and now just had to wait for the concrescence to manifest. Our only task was to identify, if possible, when and where the concrescence would occur. For my part, I had no stomach for another expedition. I was happy to be back in ordinary reality and not eager to put my ass and sanity back on the line. Moreover, I argued, what we’d experienced was an irreproducible event. It was the classic Heraclitean conundrum: we couldn’t travel the same river twice. What happened, I argued, shouldn’t be called an experiment for several reasons, but most notably because it couldn’t be repeated. We could call it the singularity, the occurrence, or the events at La Chorrera, but whatever it came to be known as, an experiment it was not.

I had thrown myself into my studies, by then redirected toward science, which I believed (and the Teacher agreed) would give me the tools to understand our experiences. I belonged in school. According to Terence, his friends were troubled enough by his singular focus to encourage his return to the field, literally—back to the mist-enshrouded pasture from which his obsessions had sprung. He needed to get away. What’s more, unlike me, he and Ev had the means to do so, having bought a quantity of emeralds just before departing Colombia. Back in the States, they’d sold them for enough to travel and live modestly in South America for the foreseeable future.

By mid-July they found themselves downriver from Puerto Leguizamo, pressing ever deeper into the jungles of the lower Putamayo. Over the weeks ahead, they re-navigated the maze of rivers, drawn by the siren song of the fungal fruiting bodies that grew near an isolated mission on the Río Igara Paraná. They arrived in late August. Aside from the rare letters they entrusted to the police captains at various towns along their route, I’d hear nothing from them for nine months.

After my summer classes ended, I moved into a communal house a couple of blocks down Pine Street from where I’d lived the year before. My housemates were a familiar assortment of counterculture types, with one exception: Beverly, a fellow student from Boston whom I immediately liked. Intelligent, studious, Jewish, and cute, she had an infectious laugh and liked my jokes. I have no idea what she saw in me, but before long we’d gotten together. Beverly was no hippie chick. I took delight in corrupting her, but I didn’t get very far. Both of us disliked living in a house with four other people, and by Thanksgiving we’d found our own place—a tiny upstairs apartment a bit closer to the foothills.

By then, Terence and Ev were on their way out. Their second visit had been less productive in terms of mushrooms, which were less abundant than before. What trips they took seemed less charged with the immanence of the Other—there were no UFO sightings, and the weather during the dry season yielded fewer mysterious anomalies. Terence did a lot of writing and thinking, however, much of which he chronicled in his journal. He continued to refine his speculations on the hidden patterns of time despite a frustrating lack of reference materials. His first predicted date for the concrescence—his twenty-fifth birthday in November—came and went without incident, a disappointing test for the timewave in its prototypal form.

Word had reached him via our father that a plea deal for his prior smuggling activities might be in the offing. The time seemed right for heading home. The trip was full of delays, weeks spent in mosquito-infested, riverine outposts that wore them down. They finally reached a city we’d passed through earlier, Florencia, the capital of the Department of Caquetá in southeast Colombia. In a chance encounter in a tienda, they met a guy who was home for Christmas from Europe. The son of a local journalist, Luis Eduardo Luna was about a year younger than Terence. Terence was trying to buy a few items using his broken Spanish. Luis Eduardo, overhearing him, offered in perfect English to help. Luis Eduardo had been studying philosophy and literature at the Universidad Complutense in Madrid. After hearing an account of what had led the weary travelers to Florencia, he invited them to stay in a small house his family owned a few miles out of town. Thus began a friendship that was to last until Terence’s death.