The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (65 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

Two weeks after Caitlin’s birth I left for the Bay Area to find us a place to live and get ready to start my new postdoc at Stanford. Sheila stayed in Bethesda. On my drive in the Honda, I stopped in West Lafayette, Indiana to visit Dave Nichols at his lab at Purdue University. Nichols was a medicinal chemist who, like Shulgin, had focused his research on structure-activity investigations of psychedelics. Unlike Shulgin, however, he had far better tools at his disposal in his well-funded lab at Purdue, so he was able to carry his work much farther than Shulgin was able to do. I’d met him at the psychedelics conference at Esalen four years earlier, and even discussed the idea of doing a postdoc at his lab at one time, before circumstances led me elsewhere.

What I found at Purdue was certainly an interesting scene. This was the place to be if you had a serious interest in psychedelics. He and his graduate students were actively involved in pursuing studies on the molecular characterization of the 5HT

2A

receptors, developing animal behavioral protocols to assess the activity of new compounds, and studying the structure-activity relationships of psychedelics in all classes. They had it all: medicinal chemistry, pharmacology, animal models—not to mention an ever-changing pool of students who loved Dave and were happy to put in long hours in the lab. He was passionate about his work, and it was infectious. Dave’s group was on the cutting edge of neuropharmacology and many of his graduate students went on to make their mark on the field. It was a stimulating research environment, and I left a little jealous. But I had my own career track to pursue at Stanford, and I was eager to get started.

Once I got to the Bay Area, I quickly found a house to rent in Redwood City, and Sheila and Cait flew out to join me. Sheila and I had agreed that she would be a stay-at-home mom for as long as we could afford it. Not having two incomes caused some economic hardship, but we have never regretted the choice of giving our daughter the benefit of a mother’s presence for the first twelve years of her life.

I saved a little money by taking the bus to work as far as I could, and then walking the last leg to the lab. My new supervisor, Stephen Peroutka, was a few years younger than I was and yet already an up-and-comer in the serotonin field. We’d met at the annual Society for Neuroscience meeting in New Orleans six months earlier and hit it off. He was also interested in serotonin receptor subtypes and wanted to further characterize the 5HT

2A

receptors with the new “hot” iodinated DOI. Like many other investigators, he was also getting very interested in MDMA.

New evidence was emerging that MDMA, by then illegal, was selectively neurotoxic to certain serotonin neurons, at least in rats and primates. Meanwhile, MDMA was becoming increasingly popular as a “club drug,” and law enforcement authorities had begun to voice concern about having another drug-abuse “epidemic” on their hands. That, plus the indications of neurotoxicity, meant there was lots of funding through the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and other agencies to investigate the neurotoxic effects of MDMA.

Steve’s lab was all over this. We co-wrote a definitive review of the current understanding of MDMA neurotoxicity, and that became my first publication from his lab, and the first paper to be published in

Journal of Neurochemistry

in January 1989. Later in my postdoc, with Shulgin’s help, I published a paper on the structure-activity relationships of a series of MDMA analogs, correlating their effect on the release of tritiated dopamine and serotonin from rat brain synaptosomes, with differential neurotoxicity in rats. To put that simply, I was looking at whether these ecstasy-like compounds damaged rat brain nerve cells. It turned out to be a nice piece of work. Peroutka didn’t sign on as a coauthor, but he let me publish it together with Shulgin and another postdoc.

I don’t recall why he chose not to join in the publication. I do know that by then MDMA was a political football in science. Any findings that suggested a lack of neurotoxicity, let alone that—gasp—the substance might even have therapeutic benefits, were heresy. According to our results, many of the analogs we tested had little or no neurotoxicity—findings that were not in synch with conventional wisdom or the expectations of the funding agencies. In a letter that appeared in the

New England Journal of Medicine

in late 1987, Peroutka noted that a survey of 369 Stanford undergraduates found that 39 percent of them had tried ecstasy at least once. I suspect he took some heat for that.

For me, the MDMA work was interesting but not really my main focus. I was still interested in characterizing the 5HT

2A

receptor subtypes, and learning more about the applications of the receptor-binding techniques. Steve’s lab was the perfect place to do that. There were four or five other postdocs as well as undergrads working in the lab. The place was a paper mill; if we didn’t submit a paper at least once a week, we weren’t working hard enough. I don’t mean that I had to submit a paper, but collectively the lab had to keep pace.

In this competitive environment, with its emphasis on the quantity of scientific publications, quality may have been compromised at times. At the time, all kinds of novel subtypes for various neurotransmitters were being described in the literature, and the serotonin field was particularly active in this regard. Steve was very interested in discovering new 5HT receptor subtypes, and indeed had already done so. He really wanted to find a new hallucinogen-specific 5HT

2

subtype, and that was the task we diligently, if not obsessively, pursued. The consensus among most neuroscientists involved in this work was that the 5HT

2A

selective agonists like DOI bound to a high affinity conformation of the receptor, not to a distinct receptor for such compounds. This was the current understanding of the molecular pharmacology of the 5HT

2A

receptors at the time, and it made sense. But Steve insisted that what the radio-labeled agonists had indicated was a distinct subtype—that is, the “real” hallucinogen receptor. After I learned more about the high-affinity agonist binding characteristics of the 5HT

2A

receptor, it was clear that we had embarked on a wild goose chase in search of this mythical receptor. Other papers we turned out were better, including one in which we screened a series of tryptamine analogs against 5HT

2A

and 5HT

1A

receptors (McKenna et al. 1990). This one received kudos from Dave Nichols at Purdue, which made me very happy.

After our return to California, we lived for about a year in Redwood City and then rented a house in Menlo Park near East Palo Alto, which for a while back then was known as the country’s “murder capitol.” Despite its location, the house was wonderful, a Spanish Colonial Revival place built in the mid-1920s with a big unkempt backyard, an old chicken shed and other outbuildings, room for a big garden, and even its own well. The place had been a part of an intentional community formed by a group of freethinkers who supported biodynamic gardening and communal living. Our dwelling had been one of several small household farms in a loose-knit cooperative whose families shared their skills and resources to support each other while selling produce in San Francisco. Our house, which we called “Housie” at Cait’s insistence, was the rare spread that was still more or less intact. It was a great place for Caitlin and our two cats, and we loved it.

When we first came to the Bay Area, we hardly knew anyone, other than Terence and Kat; they lived up north in Sonoma County, and we saw them infrequently. Our limited social life suited us, but we looked forward to the occasional Friday night dinners organized by Sasha Shulgin and his wife, Anne, for the crème de la crème of Bay Area psychedelic society. These potluck affairs usually took place at a beautiful home in the hills above Marin that belonged to Anne’s ex-husband. It was only through the kindness of Sasha and Anne that we were invited. We knew we had found a compatible bunch of friends when they not only encouraged us to bring Caitlin to these events, but made a big deal over her when we showed up. She would crawl around underneath the tables and chairs and through a forest of adult legs; nobody ever stepped on her as far as I know and everyone would find a chance to pick her up and engage with her. Sasha and Anne, the quintessence of an earth mother, were especially fond of her. Sasha, with his twinkling eyes, halo of wild white hair and beard, may as well have been Santa Claus as far as Cait was concerned. Cait never had much of a chance to be close to her grandparents on either side of our family, so Sasha and Anne were the ideal surrogates.

Chapter 46 - Climbing the Vine: 1991

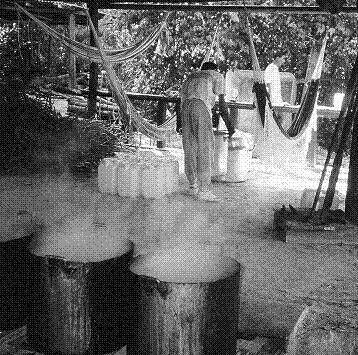

Preparing

hoasca

at the UDV temple in Manaus, Brazil.

My seemingly perpetual status as a postdoc came to an end sometime in the spring of 1990. Peroutka was about to leave Stanford for a plum position as the director of neuroscience at Genentech, the first of several positions he’d go on to hold in the world of corporate biomedicine. He told me that I should start making plans to find a real job, if such was to be had. I had been applying for various academic positions, but none of the recruiting committees seemed to know quite how to respond to my peculiar academic pedigree as a botanist/neuroscientist with a passionate interest in psychedelics. I was ready to move on from Stanford, because I wanted to find a way to merge my newly acquired skills in neuroscience and central nervous system (CNS) pharmacology with my longstanding interests in ethnobotany and natural products. But the way forward wasn’t clear, and I was worried about finding the next gig.

Then, a lucky break: I was contacted by Mark Plotkin, a Yale ethnobotanist and protégé of Schultes who would soon achieve national fame for his 1993 book

Tales of a Shaman’s Apprentice: an Ethnobotanist Searches for New Medicines in the Amazon Rainforest

. We had met briefly when I attended a presentation he made at NIH. There was a new startup company being formed in the Bay Area called Shaman Pharmaceuticals, he said, and its mission was focused on ethnobotanically driven drug discovery, especially drugs from the Amazon Basin. They already had one antiviral candidate in the pipeline, and were planning to create a CNS drug discovery program. They needed young, smart, ambitious people like me.

Shaman Pharmaceuticals was the visionary brainchild of Lisa Conte, an ambitious young entrepreneur who had been a vice-president at a venture capital firm with offices in the area. She had managed to garner about $4 million in venture capital funding as well as personal funds and had founded Shaman after observing local healers using plant medicines during travels in Asia. Schultes, and later the famous pharmacognosist Norman Farnsworth, were persuaded to join their advisory board. At the time, Conte needed people to join the core team, Mark told me, and they were hiring. I should go talk to her, which I did.

For me, it was like a dream come true. Ever since San Diego, I had made efforts to found a company that would do exactly what Shaman Pharma intended to do. I had good ideas for drug discovery but no business experience or expertise whatever. Now here was a new company run by those with the business skills to realize what I had only dreamed of doing. Moreover, I had something to offer, in the form of the skills I had developed during my postdocs at NIMH and Stanford. Although their primary therapeutic target was antivirals, they also were interested in novel analgesics and needed people to work in both areas.

My stint at Shaman would be my introduction to corporate science. I stayed with the company until the end of 1992 and enjoyed my work there. The other scientists, with some exceptions, were a good bunch to work with, and we believed in our mission. I felt like I had a contribution to make.

For most of my tenure at Shaman I was a lab rat, working in the receptor lab on the lower floor of their facility in San Carlos. Other Shamanites got to travel the world in search of exotic plants, a role I might have envied had I not been so happy to stay at home with my wife and young daughter.

In 1991, I did escape temporarily, thanks to an invitation I got to describe my work on ayahuasca at a conference in São Paulo, Brazil. The conference had been organized by the medical studies section of the União do Vegetal, or UDV, one of the syncretic churches in Brazil that uses ayahuasca as a sacrament. (Ayahuasca, in Portuguese, is called

hoasca

, and UDV followers often refer to it as

vegetal

). The conference was a multidisciplinary event that included chemists, neuroscientists, pharmacologists, anthropologists, and psychiatrists. My friend Luis Eduardo was there along with other knowledgeable figures.