The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (56 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

Back at the herbarium, Ayala informed us that the

Heraclitus

had arrived the previous night. We all piled into the street and went down to the dock to see it. The boat wasn’t the gleaming white, graceful craft I had envisioned, but a black vessel with a ferro-cement hull and the silhouette of a Chinese junk. It was also a lot smaller than I had imagined. It was definitely not the RV

Alpha Helix

with its white-coated waiters, crystal champagne glasses, multiple labs, and luxury berths. Still, if our party could fit onboard (and that looked doubtful) we’d make it work.

I met Robert Hahn, the director of the expedition, and some of the crew, who preferred to be addressed by nicknames, among them Moving, Moondance, Nada, and Bamboo. This was the first of many peculiarities that would surface about this group over the next few days. What I learned from Robert was disappointing. He didn’t see his vessel going anywhere before April 1, then six weeks away. That wasn’t going to work for us. Terence was due to arrive in two weeks, at the end of February. We had to find a way to get out of Iquitos and reach the collection areas or all our efforts would have been fruitless. Robert suggested that we might be able to take one of his small speedboats and go on ahead with two crewmembers. The

Heraclitus

would meet us later at Pebas. This wasn’t what we’d been promised, but I thought it might work.

I returned to Pucallpa with my report on February 17. Robert had heard that Nicole was in Pucallpa and invited her to visit the boat and possibly join the expedition. Don and I were delighted when she agreed to fly back with us. We were a frazzled trio by the time we arrived and found modest lodgings just off the Prospero, the bustling main street of Iquitos’s commercial sector.

The next few days were filled with logistical preparations for our trip downriver. Terence’s scheduled arrival was on February 28, which seemed to pose another delay, but that turned out to be the least of our problems. I soon saw firsthand why successful military campaigns require a commander at the top functioning as a dictator. Our plan of heading downriver to Pebas and then north from there, up a network of Amazonian tributaries, required a simple coordination of machines, supplies, resources, and personnel. But what should have been relatively easy became almost impossible given the consensual style of decision-making insisted on by our new shipmates. Despite their hype and bravado, the Heraclitistas, as we dubbed them, appeared to be, if anything, even more clueless than we were about how to stage this event.

Meanwhile, in my absence, the

Heraclitus

had come out the loser in a tangle with a barge while tied up at the port and now had a fifteen-inch hole in its cement hull. The vessel wasn’t going anywhere for the foreseeable future except dry dock; the materials for repair had to be shipped in from Lima. Even the absurd departure date of April 1 now seemed like an optimistic fantasy. We had no choice but to go with Robert’s speedboat plan. The welcome news that Nada and Moondancer would be joining us was tempered by the realization that there wasn’t room for everyone on the boat, let alone our gear and supplies.

A rumor had surfaced that Wade Davis, then a student of Schultes, was on his way to Iquitos from Ecuador and might join the expedition. Luckily, this proved to be true. He had been asked—and had tentatively accepted—to be the voyage’s chief science officer and soon arrived to check things out. None of us knew Wade well at the time. A native of British Columbia, he’d briefly been a forestry student at UBC and had taken some courses under Neil Towers before I joined the program. He’d left for Harvard when the chance arose to work with Schultes. A skilled outdoorsman, he already knew his way around South America, and I welcomed his arrival. With our inexperienced crew, we needed somebody with a strong personality to come in and take charge.

Meanwhile, it had become quite clear that the Heraclitistas were not only disorganized and dysfunctional but rather weird. They had a humorlessness about them that seemed out of place in easygoing Peru. There were intimations of a hidden agenda, or at least things about themselves they hadn’t fully explained. We knew that the Institute of Ecotechnics, which owned and operated the

Heraclitus

, was loosely affiliated with a theater troupe called the Theater of All Possibilities and several other peculiar enterprises. Only years after our encounter with this odd group did we piece together the convoluted and fascinating details of their story.

It turned out that the institute, the theater troupe, and even the

Heraclitus

itself could all be traced to a remarkable and enigmatic man named John P. Allen. A metallurgist turned Harvard MBA turned systems ecologist, Allen, now in his eighties, may or may not have been a meglomaniac in his heyday, as his critics claimed, but he was certainly the producer, director, and star of his own legend. In 1969, Allen and a few others had started an “ecovillage” in Santa Fe, New Mexico, called Synergia Ranch. It was there that the Institute for Ecotechnics and the theater troupe got their start. First envisioned by Allen as a vessel big enough for a crew of fourteen, with both a science lab and a theater, the RV

Heraclitus

was communally built in Oakland and launched in 1975. It has been plying the world’s waters ever since, often under sail, though the craft was relying on its engine for its long trip up the Amazon. According to the boat’s website, its Amazon cruise in 1980 had been inspired by Schultes, who spoke at a conference on jungles sponsored by the Institute for Ecotechnics in Penang, Malaysia, in 1979. On that occasion, Schultes challenged them to carry on the river mission he’d begun aboard the

Alpha Helix

. As to how that may have influenced Wade’s decision to join us aboard the black junk, I do not know.

In the mid-1980s, Allen and several colleagues founded Space Biospheres Ventures, an organization that became known for founding, managing, and eventually mismanaging Biosphere 2, a three-acre ecological research facility under glass located in the Arizona desert in Oracle, near Tucson. The project’s major financier was the billionaire Ed Bass, one of the well-known Bass Brothers from Fort Worth, whose family wealth was derived mainly from oil and gas revenues. Of the four, Ed was considered the most offbeat. In the early 1970s, he spent time at the Synergia Ranch, where he met others who shared his dual interests in drama and environmental causes.

Biosphere 2 was originally conceived as a massive, closed-system laboratory (full of plants) that simulated, in miniature, the planetary biosphere—which the founders called Biosphere 1. One goal was to study the human impact on natural ecosystems; another was to create a self-sustaining artificial ecosystem that generated its own food and recycled all its waste. Some viewed it as a prototype for an eventual colony on Mars, or even a kind of panic room after an ecological disaster on earth. The

Heraclitus

apparently cost $90,000 to build; Biosphere 2 cost $150 million, with millions more spent annually to maintain and operate it.

As proof of concept, Biosphere 2 conducted two “closure” missions during which a small group of “biospherians” hoped to remain sealed inside the enormous, greenhouse-like dome without any outside resources. All food was to be grown in the dome, and ecological dynamics would be used to keep carbon dioxide levels low and oxygen levels within acceptable limits. The first such mission, which began in 1991, lasted two years; the second, in 1994, ended in acrimony after six months. By then the entire venture had foundered amid accusations of scientific fraud and financial mismanagement. Though the project had many laudable goals, the management team’s internal conflicts and lack of scientific expertise, among other factors, eventually turned what could have been a pioneering research project into a farce. The facility has passed through other hands over the years and is now overseen by the University of Arizona. The story of Biosphere 2 and the colorful personalities that originally built and operated it is a lesson in the unanticipated outcomes born of the collision between scientific goals, human hubris, vast wads of cash, and competing personal agendas. Despite all the psychodrama, the project did produce some credible science, along with plenty of dubious science and scandalous gossip, a history recounted by Rebecca Reider in her excellent 2009 book

Dreaming the Biosphere: The Theater of All Possibilities

.

All that lay in the future on March 1, 1981, when we found ourselves gathered on the deck of the

Heraclitus

. Our departure was still a week away, but with all the players by then in town, Robert had invited us to join the crew for dinner and a group discussion of the ever-changing plans. Terence had shown up the night before, and Wade and his girlfriend Etta had surfaced earlier in the day. Don was onboard, of course, along with Al Gentry, who we’d invited to join us for the evening. Rounding out the guest list was Nicole, who was up for the party but not the expedition, having stumbled on a bit of uneven pavement and skinned her knee. The scrape would be fine, thanks to

Sangre de Grado

, but she’d been unnerved enough to reconsider being trapped with our motley bunch up a jungle river.

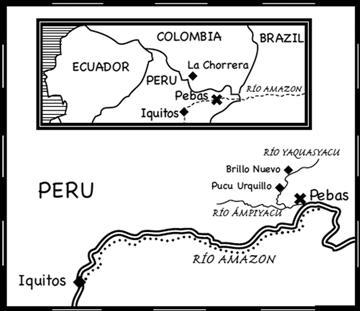

Route Map to Pebas (Map by M. Odegard)

The Heraclitistas included the captain and several others whose names I don’t recall. I do remember Terence describing one of them as looking like he’d been sleeping in an open grave. It all started out normally enough; we sat on the deck conversing, smoking, and waiting for dinner, its delicious aroma wafting from the hold below. Then the Heraclitistas started howling, an ululating keening that went on for several minutes and then ceased as abruptly as it had begun. The rest of us looked at each other quizzically, expecting some explanation, but none came. Conversation resumed as though nothing had happened. Then dinner was served, and we dug in. There was silence for a bit as we ate hungrily, and then we started chatting and joking again, as one would normally do over such a feast, until we realized we were the only ones talking. Our chatter faded, and we finished eating as the crew maintained a stony silence.

After dinner, we sat in a circle as they took turns delivering short monologues. I expected them to address the upcoming trip or its research objectives, but they did not. Their comments were mostly unrelated to what we’d been discussing, and a few made no sense at all. The crewmembers seemed to be engaging in a free-association exercise during which everyone expressed whatever happened to be on their minds. No one interrupted these monologues or ventured a response.

That made for an uneasy and somewhat bizarre evening. Absent any explanation, we felt a bit like ethnographers invited to participate in the customs of an unfamiliar tribe. We concluded their rituals stemmed from their theatrical roots. In other words, they behaved as they did, in part, because everything was a performance for them. This explanation actually helped us to understand their eccentricities. Life on the RV

Heraclitus

was a work of performance art. And maybe the same could be said of the events that unfolded twenty years later inside Biosphere 2.

Don Marcos preparing

ku-ru-ku

hallucinogenic paste in Puco Urquillo, 1981.

Wednesday, March 4, marked the tenth anniversary of the Experiment at La Chorrera. It was not a good day for me. Since my departure from Vancouver in January, my communications with Sheila had been sporadic, as often happened on trips to remote locales in those pre-Internet days. I was pleased to find an aerogramme from her waiting for me when I showed up at the herbarium that morning. I wasn’t pleased by its contents, which amounted to a Dear John letter. She had grown lonely, she said, during the weeks of my absence and had started dating another student in the department. One thing had led to another, and now they were getting seriously involved. She had written to let me know that our relationship, on which I had placed such hopes for the future, was over. I was stunned and angry. I couldn’t believe that her feelings for me had turned out to be so short-lived. Just weeks before I’d left, I had come to believe, or had let myself believe, that Sheila was “the one” and that our destinies were intertwined. I’d now discovered otherwise, just as I was heading into the jungle for what we guessed would be seven weeks. This news plunged me into a depression that hung over me for the rest of my time in Peru.