The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (54 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

The Amazon and Orinoco watersheds, with their teeming diversity of life, had been drawing Western scientists for more than two centuries. Among the earliest were Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt and the French botanist Aimé Bonpland, who arrived around 1800. One could argue the modern era began in the 1840s with the Amazon journeys of the British evolutionary theorist Alfred Russel Wallace and Richard Spruce, perhaps the greatest botanist of his day. A century later, a young Schultes modeled his career after Spruce’s and then went on to inspire a new generation of plant hunters, to which I belonged.

No sooner had I signed on for my voyage than I began encountering some of my illustrious contemporaries. The first was Timothy Plowman, Schultes’s protégé, who was working at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, home to an impressive collection of Peruvian plants. Our consultations with Plowman primed us on what to expect in Peru. Tim had spent a lot of time in South America and was happy to share his experience with us. By then the world’s leading expert on the coca plant, he was widely regarded as the heir apparent to Schultes. Many ethnobotanists, myself included, were saddened when Tim died of AIDS in 1989. The field had lost a talented scientist and a good man.

In Lima, we visited the herbarium at the Museo de Historia Natural and the government offices that issued collection permits (which were easy to get back then). A few days later, we flew on to Pucallpa, a rough, tough, Amazonian frontier town on the Río Ucayali. The place was a pit, literally. A mud-caked bulldozer, half sunk into the mire of the unpaved main street, looked like it had been there for months. We checked into a nearby flophouse. If it’s possible to give a hotel a negative five star rating, this place qualified. Our room had no air conditioning, no hot water, and a single fluorescent light in the ceiling. There were two filthy mattresses without sheets, and it looked like someone had bled to death on one of them. From what we could see, the favorite forms of recreation were drinking, fighting, and playing loud music until three a.m., all of which we could watch through a grimy window above the street.

Breakfast in the dining room at another hotel on the corner consisted of an egg sandwich and Inka Kola, the fluorescent, greenish-yellow soft drink loved by many, apparently, but which tasted to me as ghastly as it looked. As usual in Peru, coffee was a syrupy concentrate made from Nescafe that one diluted to taste with hot water. We’d encounter this preparation everywhere and grew to loathe it. While the country appeared slow to embrace the concept of freshly brewed coffee, despite growing some of the best in the world, Pucallpa at least was ahead of its time when it came to the drive-thru window. Some of the locals enjoyed bursting through the swinging, saloon-style doors on their motorcycles to order breakfast. It was all very entertaining and a bit shocking for two mild-mannered Canadian graduate students.

Our first field trip took us out to Puerto Callao, a town on Lago Yarinacocha, an oxbow lake cut off from the Ucayali. There were a few indigenous communities nearby, including a Shipibo village called San Francisco, but we were bound for another enclave, the Peruvian headquarters of a global operation known as the Summer Institute of Linguistics. Established in the 1930s, the SIL ostensibly sought to promote literacy among indigenous peoples and to translate the Bible into indigenous languages. By then, the SIL had established a far-flung network of outposts as well as ties to many top linguists and anthropologists. Now known as SIL International, the nonprofit organization drew support from evangelic churches, which helped to pay for the planes and boats that gave them access to remote cultures. Though the group denied being a missionary organization, rumor had it otherwise. Later, the journalists Gerard Colby and Charlotte Dennett would argue that the SIL had been entangled with American oil interests and even the CIA, with dire consequences for both the Amazon region’s native peoples and their land (Colby, 1995).

We were somewhat aware and leery of the group’s reputation, but we had bumped into one of their linguists on the plane to Pucallpa, who told us we’d find a colleague of ours there known to us only by reputation: Nicole Maxwell. Given the name of another SIL linguist who could help us find her, we headed to the compound to track her down.

What we found at the SIL base was a surreal piece of small-town America lifted up from Iowa or Nebraska and plunked down in the Amazon, complete with modest bungalows, white picket fences, sidewalks, and neatly trimmed lawns—not to mention a white church with a steeple. It was like an evangelical theme park designed to make its inhabitants feel at home, or at least feel anywhere but where they were. Even the residents seemed to be playing roles in one of those tourist recreations of an authentic village, Valley Forge or Old Richmond, where the employees wear period dress and pretend to be blacksmiths or chandlers. In this case, the village was a recreation of a 1950s, Mayberry-style town. I got the feeling the people were politely “nice” to us in a way that let us know they really viewed us as degenerate hippie scum. Our inquiries eventually led us to Nicole having Sunday dinner with one of the local families.

Nicole, when she came to the door, was a refreshing dose of reality. Tall, rail-thin, and ancient, she was already a legend in the small world of ethnobotany, partly because of her book

Witch Doctor’s Apprentice

, first published in 1961 (and reprinted in 1990 by Citadel Press with an introduction by Terence). The book is her account, most likely embellished, of her quest to find medicinal plants in the Amazon, beginning in the late 1940s. Having grown up a wealthy San Francisco debutante, Nicole became a well-known, free-spirited figure in Paris during the twenties, occasionally dancing with the Paris Opera and modeling nude. After the end of her twelve-year marriage to an air-force officer, she moved to South America in 1945 and became a correspondent for the

Lima Times

, according to her obituary in

The New York Times

. Her fascination with jungle medicine began on a trip into the rainforest. After she’d been badly cut by a machete, her Indian guide treated the gash with a folk remedy known as

Sangre de Grado,

or “dragon’s blood,” derived from a reddish sap. We now know the source of this wound-closing sealant was the latex from

Croton lechleri,

a “euphorb” like those my colleague Don was studying. The gash quickly healed without becoming infected or leaving a scar. Thanks to that experience, Nicole discovered the mission that was to define the rest of her life: ferreting out jungle remedies and trying to interest big drug companies in developing them. Like many other ethnobotanists, she didn’t have much success, but her story was compellingly told, and by the time I met her she’d become a legend. We became fast friends, and I remained in touch with her until she died, impoverished and largely abandoned, in a Florida nursing home in 1998.

When we first met on the porch of the bungalow, she still cut a dashing figure even for a frail lady of seventy-five. The white-bread surroundings made her earthiness stand out all the more. Her profanity would have put a longshoreman to shame. She insisted she owed her long life and good health to smoking at least a pack of unfiltered Peruvian cigarettes a day, washed down with a quart of

aguardiente

, a popular liquor distilled from sugarcane.

We had a lively conversation when she dropped by our hotel the next afternoon. Nicole had a habit of jumping from topic to topic, rarely focusing on anything for more than a moment, but we did get her to pass on some contacts in the Iquitos area that proved useful in our search for

oo-koo-hé

. We promptly abandoned the muddy center of Pucallpa for a place called El Pescador, a cheaper, quieter hotel in Puerto Callao, after Nicole said she’d find us a place to store our supplies. In return, we helped her move out of an apartment in Callao and into a house on the SIL base. Over the next few days, we spent a lot of time with Nicole and her circle. Most of them were affiliated with the SIL but weren’t missionaries. Despite my earlier skepticism, they proved genuinely friendly and quite helpful.

Our next task was to locate Don Fidel Mosombite, the

ayahuasquero

that Terence and Kat had met in 1976 when they’d traveled to Peru in search of the brew. We had no address, only his name and vague assurances that a certain woman herbalist at the market could put us in touch. When we finally connected with her, she arranged for one of her sons to take us to see him.

The man who opened the gate was a stocky, barrel-chested man who could have been anywhere from forty-five to sixty. He lived with his young wife, the baby girl she was nursing, and two boys who looked to be about five and six. Neither Don nor I spoke much Spanish, but I haltingly introduced myself and mentioned Terence and Kat. I said as best I could that we, too, wanted to learn about ayahuasca, the plants it contained, and his methods of preparing it. Don Fidel projected considerable gravitas; it was clear he was an intellectual, or rather a sage, a man who knew many things, though not a scholar as most would think of it. Whether he was actually literate or not, he was a genuinely wise and generous man who was willing to share what he knew.

In conversations we had over the following days, he conveyed some of his knowledge about the plants and their properties, about his understanding of cosmology and the way the sacred world was organized. The world is divided into three realms, he said: the earthly realm, the upper realm of God, and the lower of the devil and demons. When one takes ayahuasca, he said, one sees enchanted cities in the upper realm and lost cities in the diabolical realm. Everything he knew about the healing properties of plants and how to prepare such medicines had been taught to him by ayahuasca in the trance. Surprisingly, he said that he sometimes used mushrooms, but he regarded ayahuasca as very different, and much stronger. Except for his comment about mushroom use, the rest of his statements were consistent with what other ethnographers had said about practitioners of

vegetalismo

, which is the syncretic

mestizo

tradition in which Don Fidel was firmly embedded. After a few conversations, I realized Don Fidel, then fifty-six, was a genuine shaman, a practitioner of long experience, and in every respect the real deal. He was as good as any

ayahuasquero

I’ve ever drunk with, and better than most.

A few days later, I had my first real encounter with ayahuasca. While living in Hawaii, I’d tried a sample that Terence had brought back, but I’d felt no effect other than the expected purging. Here was a chance to drink the real thing, in a traditional setting, freshly made and presumably strong. When we showed up at 7:30 on a beautiful moonlit night, Don Fidel was already seated at a crude table at one end of the one-room hut. He had a plastic bottle filled with an orangey-brown liquid and had removed the wooden cork and was softly whistling into it. He informed us the “

la purga,

” was “

muy fuerte

” and “

bien

bueno

’” (very strong and very good). Don and I sat for a while in the gathering dusk as others drifted in: three men, one of whom was apparently Don Fidel’s apprentice; two women, one of whom was pregnant; another woman with swollen legs whom Don Fidel had been treating at the house that afternoon; and Don Fidel’s wife.

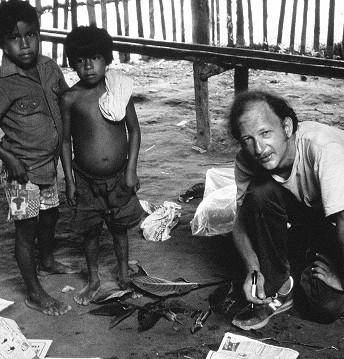

Dennis and helpers preparing voucher specimens, 1981.

We all sat on narrow and uncomfortable wooden benches arrayed along the inner walls of the hut. Another plant substance that figured in the setting was

mapacho

, a South American tobacco variety known for its strength. We smoked and chatted quietly in the gathering gloom until Don Fidel brought down a small cup fashioned from a gourd. He uncapped the bottle, blew a little more

mapacho

smoke over it, whistled, and then filled the cup to the brim and handed to me. It was bitter and acrid, but I was prepared for much worse. I tasted it and then knocked it back in a single gulp. Those who are familiar with ayahuasca will say that the first taste is always the best; it only gets worse after that. Having taken it now several hundred times over the last thirty years, I can attest to the truth of this. And yet somehow I always get it down.

I retired to my place on the bench while Don went forward to receive his portion, and then sat back down beside me. One by one, all of the men received their allotment, taking less than we did; Don Fidel took about a cup and a half. The women did not drink. We settled in to wait. Conversation ceased; presently there was only the gentle creaking of Don Fidel’s wife rocking in the hammock, the ever-present trill of insects, and the distant barking of dogs. After a little while Don Fidel reached up and extinguished the single candle on the shelf above my head, and then began to sing his beautiful

icaros

. Some of his songs were in Spanish; others were in a language I didn’t recognize then but I now know was Quechua. His apprentice, Don Miguel, softly joined in.