The Bundy Murders: A Comprehensive History (32 page)

Read The Bundy Murders: A Comprehensive History Online

Authors: Kevin M. Sullivan

"Jerry, you seem to be a pretty good detective."

"I think I'm a damned good detective," said Thompson soberly.

"But, Jerry, you're just grasping at straws," continued Bundy. There was mirth on his face as he continued. "Just straws, Jerry. But you keep at it Jerry. If you find enough straws, maybe you can put a broom together."'

Bundy had no idea how prophetic his sarcasm was. Thompson had indeed begun making a broom, and in time, that broom, which had already drastically altered Bundy's life, would sweep it away. He was too arrogant to know this.

Communication between the three lead investigators in the Bundy case - Bob Keppel in Seattle, Mike Fisher in Aspen, and Jerry Thompson in Salt Lake -was now both steady and fruitful. What had at one time been three separate investigations was now a unified effort to bring Theodore Robert Bundy to justice. There was an undeniable excitement in the air as they, for the first time, converged on the trail of this most elusive killer. It was only a matter of time before everything fell into place, they believed. The hardest part of the investigation - discovering the identity of the perpetra- for -was now behind them. The future, however, would hold surprises of its own.

Ted Bundy had been intimately acquainted with the beliefs of Mormonism for many years, having discussed the religion with his Mormon girlfriend, Liz Kendall. Any discussion he may have had about religion, the church, or faith was unlikely to have been sincere. Bundy, who had a background in the Methodist church which he attended with his family while growing up in Tacoma, was in fact an atheist for most of his life. That he dabbled with Mormonism while in Utah had nothing to do with a sudden appeal to a higher calling. It enabled him to associate with people in the Mormon Church. He would freely attend meetings and accompany church groups on outings into the mountains. There were, after all, women in the group, and Bundy had both his private life of murder and open life of dating and being sociable in public to maintain.

During the month of August, an emotional time for the sociopath, what with his heavy drinking, the break up with Knutson, and the arrest, Theodore Bundy would make a public statement of faith by being baptized into the Mormon Church. From the perspective of the church, it was a natural result of an ongoing relationship he'd had with members of the faith for some time. They welcomed him gladly, and viewed Bundy as everyone had viewed him while he wore his elaborate mask. He was well-liked and trusted, and they saw only what he wanted them to see. But the relationship was destined for destruction from its conception, as Bundy's legal problems would, after a time, require them to withdraw from him, if not their love, at least their support. The Mormon Church's newest son would prove to be a disappointment, and if Bundy was looking for a cheerleading section as the authorities closed in, he'd have to seek it elsewhere.

Within days of visiting the University of Utah School of Law, Jerry Thompson, Detective Ira Beal, and another investigator caught a plane to Seattle to interview Liz Kendall. Liz, who'd broken off her engagement to Bundy after his arrest, agreed to speak with the detectives in Bob Keppel's King County Police Department office. Thompson would not come away from this session with anything substantial, but he would hear from Liz about the strange side of Theodore Bundy. This fit perfectly with what he already believed Bundy to be.

Kendall's willingness to talk about Bundy didn't mean a complete end to her vacillating. She'd later regret this meeting, and other admissions to other authority figures later on. She had gained some emotional ground in cutting her ties to the man she once thought she'd marry, but it appears that hope remained alive. Hope allowed her to believe that somehow, someday, all of this speculation would come to an end, and he would be proved innocent. She didn't understand how completely lost was the dream she once believed would become a reality, nor did she understand how quickly the detective from Utah would bring this thing to a head.

On the afternoon of October 1, 1975, Jerry Thompson and detectives Beal and Ballantyne from Bountiful made a surprise visit to Theodore Bundy's apartment. There must have been an almost tangible sense of anticipation as the trio of lawmen climbed the steps of 565 First Avenue, and Bundy, who was just stepping out of the shower, did not hear them approach the apartment marked number 2. When the knock came, Bundy threw a towel around his waist and opened the door. When he saw the man who was relentlessly pursuing him, he greeted the somber-faced detective with a smile and said, "Hi Jerry ... to what do I owe the honor of the visit?"' Bundy, always socially correct in public, invited the men to step inside.

Thompson, who was pulling a subpoena from his pocket, informed Bundy he had something for him. At that moment, Bundy started to turn pale and all three men watched as their suspect's heart could be seen pounding in his chest. Having committed so many murders, and knowing he'd been under almost constant surveillance by police, he no doubt envisioned an arrest warrant for the slaying of one of his Utah victims. However, when Thompson told him the court-ordered appearance was for a lineup, he quickly regained his composure and said, "Oh, is that all?"' In all of his dealings with Bundy, this was the only time Detective Thompson ever witnessed him losing his composure. After this, he would remain calm and collected no matter what the circumstances.

As soon as the detectives had driven away, Bundy got dressed, grabbed his wallet and keys, and took off down the steps. The one thing he could do, he reasoned, to lessen the possibility of being identified was to cut his hair. When he was handed the subpoena, his hair was thick and bushy, and very similar to its appearance in November 1974. By the time he walked out on the platform the next morning, he reasoned, his hair would be trimmed very short and combed on the opposite side. Chances were that he would appear nearly identical to the other men standing beside him. Thinking these thoughts, it is unlikely Ted Bundy felt any real concern as he contemplated walking into the midst of those trying to destroy him. He had outsmarted the police many times before, and believed he could again.

When Thompson saw Bundy the next morning he was aghast, and envisioned his case evaporating before him just as it was getting started. In actuality, he had nothing to worry about. All three witnesses who were present that day - Raelynne Shepard, the drama teacher from Viewmont High; Tamra Tingey, locker mate of Debbie Kent who remembered seeing Bundy that night (she thought he was very handsome); and Carol DaRonch - all identified Ted Bundy from the lineup.

When Bundy's attorney, John O'Connell, informed him that he'd been identified, the shock was evident on Bundy's face. He never dreamed an investigation would get this far, even one that had been steadily going against him. Still, he would, like an infection resisting an antibiotic, immediately adapt to his situation and take up the mantle of a man falsely accused. That would come later. But on October 2, 1975, Theodore Robert Bundy was charged with kidnapping and attempted murder, and his bail was set at $100,000. In today's dollars that would be the equivalent of some $400,000. Bundy would remain in jail for two weeks until his bond was reduced to $15,000, a far more manageable sum for his family and friends. Before being led away, Bundy was allowed to make one phone call. He decided to call Marlin Vortman; a wise choice, as Vortman was perhaps the most able to help Bundy of anyone in Washington State. Not only did Vortman believe in his innocence, but he would give Bundy his ear in all things legal, and Bundy needed that. Vortman, he correctly believed, was a powerful friend, and one he could count on in his present trouble.

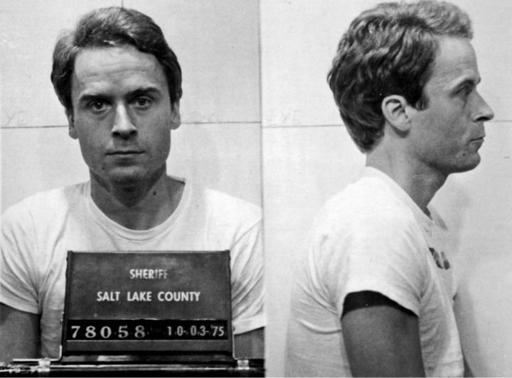

Ted Bundy (second from right) stands in a lineup at the Murray, Utah, Police Department, on October 2, 1975, where he is identified by Carol DaRonch as her abductor (courtesy King County Archives).

The very next day the media storm broke. Friends and former associates heard of the arrest and were hit with a sense of shock and bewilderment. How could this have happened to him? The Ted Bundy they campaigned with, had a beer with, and sat across from in class? It just couldn't be, they said. Yet over time, each would experience an epiphany as to his guilt. For some, it would not come until the end-of-life confessions Bundy would eventually be forced to make in his feeble attempt to stave off execution. But for Ross Davis and many others like him, over a period of time, when layer after layer of circumstantial evidence mounted, they came to the realization that their former friend was in fact the diabolical killer who had terrorized Washington State and beyond.' Stuart Elway, who'd campaigned with Bundy and had, at one time, planned to share an apartment with him, said, "After this, we were forced to reevaluate what we believed about our friends.""

A somber Ted Bundy less than 24 hours after being identified as the man who attacked Carol DaRonch. Here he is standing for his second mug shot at the Salt Lake County Sheriff's Office (courtesy King County Archives).

Those investigating the grisly murders in the state were either convinced of Bundy's guilt or soon would be. Yet they were not ready to admit that to the public. The October 3 headlines told the tale. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer proclaimed, "Is Utah `Ted' Seattle `Ted"'?

Bundy's hometown newspaper, the Tacoma News Tribune, trumpeted: "Tacoman not `Ted' murder suspect," and quoted Captain Nick Mackie of the King County Police as saying Ted Bundy "`could not possibly' be responsible for the `Ted' murders here."

But most people began to see the connections among Ted Bundy, his Volkswagen, his move to Utah, the start and stop of murders in Washington State, and all the other little circumstantial tentacles linking him to the horrible crimes. The average person saw the links, and a flat rejection from the authorities would not sway public opinion. Even so, the October 4 headline in the Tacoma News Tribune continued the official line: "Police maintain Bundy not `Ted,"' although Captain Mackie was quoted as saying, "We have no evidence to say he was `Ted,' and we have no concrete evidence to say he wasn't."

Even while the Ted-weary citizens of Washington were sipping their first cup of coffee for the day and mulling over the wall of denial Captain Mackie was building, detectives Robert Keppel and Ted Fonis were hopping a United Airlines flight to Utah. Keppel telephoned Jerry Thompson to set up a meeting even before heading to their hotel, where Thompson soon met them. Here the three investigators discussed the murders and Ted Bundy in detail, and it appeared to the Seattle pair that Utah had a good case against him."

It would be a long but productive day for the trio of lawmen. Homicide reports, missing persons reports, autopsy reports, and other investigative reports were retrieved from metal file cabinets, viewed and copied. Photographs of the decedents from Utah and Colorado were studied with respect to the damage done to the skulls of the young women. The similarities to their Washington counterparts were noted. While in Murray (where Bundy's fate ultimately rested), Thompson gave the detectives a tour of the Fashion Place Mall and drove the men along the same route Bundy had taken with Carol DaRonch to the McMillan School where he attacked her. Thompson also filled them in on the details of the Kent abduction and the ongoing investigation in Bountiful.

The only disappointing aspect of their trip was that they were not able to view the now-infamous gym bag containing the murder kit which had been recovered from Bundy's car during his August 16 arrest. "We also were interested in viewing real evidence found in Bundy's VW," Detective Fonis noted in his report. "We were told that due to their hunting season (elk and ducks) that we would probably be unable to view this, as they have one Evidence man, and one key, and he is presumably out of town. 1112 It didn't help matters that they arrived on a Saturday. Had they arrived a day earlier, the evidence man would no doubt have waved at them to follow him, and in short order they would have been handling those items so personal to the killer. Not wanting to leave Utah without seeing them, Keppel and Fonis asked Thompson on Sunday to contact Captain Pete Hayward, as he might be able to locate the key to the evidence room. But Hayward was also out hunting and couldn't be located. When they flew back to Seattle later that evening they carried with them a black-and-white photograph of the items shot on the night they were confiscated from Ted Bundy. Jerry Thompson also promised to mail them additional photos of Bundy's VW.