The Bundy Murders: A Comprehensive History (37 page)

Read The Bundy Murders: A Comprehensive History Online

Authors: Kevin M. Sullivan

Bundy was but Act 2 in a theater of the absurd playing itself out in the old Aspen courthouse. Just a day before Bundy's first appearance in court, Judge Lohr had pronounced sentence (albeit a light one of thirty days) on French singer Claudine Longet for the shooting death of Aspen celebrity Spider Sabich. The court determined it to be a criminally negligent homicide, allowing Judge Lohr plenty of room to show mercy to the apparently distraught Longet. This did not please the family of Mr. Sabich, and many a tongue could be found wagging in public circles suggesting justice had not been served in the matter.

In April of that year, because of a new health ordinance that said prisoners could not be held in the Aspen jail for longer than thirty days, Bundy was transferred to the Garfield County jail, a facility in Glenwood Springs, just under an hour's drive away. This meant regular commutes to Aspen, allowing Bundy to enjoy the beautiful Colorado scenery and perhaps quietly reminisce about the lives he had snatched in the state. How much he wanted to be out hunting again, especially now as spring was unfolding from a particularly mild winter with a less-than-average snowfall.

April was when the court got down to business with the pretrial hearings. At the hearings, the prosecution would present such evidence as the microscopic similarities between the hairs found in Bundy's car and hairs belonging to Carol DaRonch, Melissa Smith and Caryn Campbell. True, it was circumstantial evidence, but it was strong, even irrefutable evidence, for those investigators who made all of this happen.

Unfortunately, Blakey and Fisher would suffer an embarrassing setback when witness Elizabeth Harter, who had positively identified Ted Bundy in the photo lineup presented to her a little over a year earlier, failed to point him out in court. The man she recognized in court that day as looking like the man she saw standing by the elevator that cold January evening was none other than Undersheriff Ben Meyers. Those who witnessed this prosecutorial fiasco say Bundy had difficulty suppressing a smile.

Soon after the pretrial hearings came to a close, Judge Lohr granted Ted Bundy the right to assist in his own defense. Why would Bundy, after the colossal mistakes he'd made in Utah assisting John O'Connell, choose this route once again? Part of the reason was no doubt his lack of confidence in Charles Leidner, his court-appointed attorney, and Bundy, never without his arrogant pet peeves, might have felt Leidner was a step down from the likes of John O'Connell. But this move also allowed him access to the law library and the many amenities granted to attorneys, including special privileges extended to him in jail and by request. This must have appeared both ludicrous and offensive to those who knew the truth about him, but Lohr had to review each request from Bundy with the same impartiality and adherence to the law as he would have with any lawyer. More often than not, Bundy's petition would be granted.

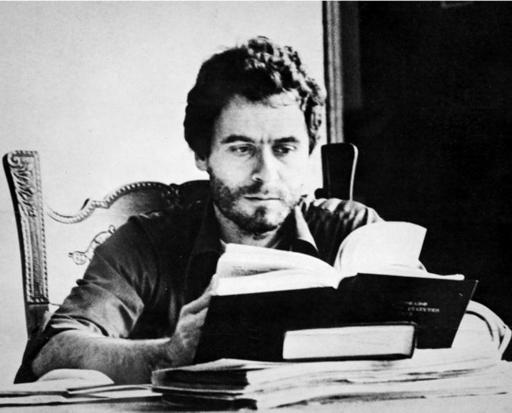

Ted Bundy, a prisoner in Colorado, studies in the jail's library and prepares for escape (courtesy King County Archives).

Acting as his own attorney would eventually bring him into contact with his former adversaries like Jerry Thompson, and others responsible for sending him to prison. He would even have another opportunity to cross examine Carol DaRonch, and as Ted-the-attorney, try to undermine her testimony once again. But beyond his antics and flair, Bundy was thinking of freedom; not a court-ordered release, but a release achieved by his own wiles born of his sincere desire to escape. He'd been thinking about flight from the moment he left Point-of-the-Mountain.

Mike Fisher, Jerry Thompson, and others familiar with the cunning Theodore Bundy warned the complacent jailers of his desire to break free and the danger that posed to the rest of society. But these warnings would fall on deaf ears. As a charmer mesmerizes a cobra, Ted Bundy had all but mesmerized those responsible for keeping him safely locked away. And because Charles Leidner had petitioned Judge Lohr early on concerning Bundy's right to appear in court without shackles, his flight, whenever he deemed the moment was right, would be an unfettered one.

That moment came on June 7, 1977. Bundy had decided to take advantage of an open window on the second floor of the old courthouse. Jumping from the window, he correctly reasoned, would save him precious time, if he could do so without being noticed by anyone on the second floor or outside on the courthouse lawn. With any luck, because of the gift of trust granted him by the guards, he believed he just might make it over the harsh mountains and ultimately to a life of freedom.

11

ESCAPE TO TALLAHASSEE

Perhaps the most recognizable photograph taken of Ted Bundy during his Colorado odyssey was snapped on the morning of his escape as he was being escorted into court. Viewing the picture in retrospect, one can almost see in his body language a transition from prisoner to escapee. He is leaning slightly forward as he walks (as if preparing to break into a run), and there is an intense, singular look of concentration in his face. His brain is focused on getting away from his keepers. Getting away from his keepers was one thing. Freeing himself from the wilds of Colorado was something else altogether.

What is not evident from the picture are the several layers of clothing Bundy had selected for his journey: one pair of underwear, two pair of shorts (a white pair and blue jean cutoffs), his corduroys, a long-john top over a Tshirt, two turtleneck sweaters, and a long, loose fitting, open-front sweater. Although the daytime temperature was mild, once the sun had set it would get quite cold and unforgiving, and Bundy wanted to be prepared for it.

When Judge Lohr pounded his gavel signaling mid-morning recess, Bundy headed to the law library. Nothing unusual about that, as the former law student had been ensconced there on a regular basis, and neither the guards nor anyone else paid close attention to what he was doing. Today, however, it wasn't the array of law books beckoning to the accused, but the window that had been opened every day to let the fresh springtime Colorado air into the stuffy old courthouse.

The escape wouldn't be easy, Bundy realized, and at any moment someone could pop into the library and bring it all to a close. As he looked around one last time at the lawn and street below (it was momentarily clear) and took a quick glance back towards the doorway, Theodore Bundy, as carefully as possible, situated himself on the window's ledge and without thinking about it any further, pushed himself away and was airborne. Less than two seconds later he hit the ground, and as quickly was back on his feet.

Working on a hastily devised plan, he ran quickly across the street, jumped over a fence and continued running down an alleyway. From here, it was only a matter of minutes until he cleared the civilized bastions of Aspen's municipal buildings and condominiums, and he took a moment's refuge in a gorge by the Roaring Fork River. Here he stripped down to his white shorts and the long-john top. After placing a red bandana around his head, Bundy wrapped his other clothing in one of the turtlenecks and tied it together in such a way as to transform it into a carrier of sorts. As he readied himself to leave, Bundy stared at nearby Aspen Mountain. Standing several thousand feet high, it was simply the first leg in his quest for freedom. If he could make it beyond the mountain, he reasoned, he could make it to Crested Butte (a difficult journey on foot without a mountain to cross), and there would be no stopping him.

But the mountain and the surrounding region would do what the guards could not do. Ted Bundy would spend the next five days wandering around in the wilderness in what turned out to be a physically and mentally draining experience, where he was lost most of the time. At one point he passed up a vacant cabin in his desire to push on towards Crested Butte. But when the elements of rain and cold set in, he made his way back, and after prying and breaking his way in through a window, fell into a deep sleep. When he awoke the next morning, he ate what little was there, grabbed a .22 rifle and some shells, a flashlight, blankets and a first aid kit, and headed out again.

Soon after Bundy jumped out of the window that morning, a passerby entered the courthouse and announced that she had just seen a man leap out of the second story window. Everyone immediately thought it was Bundy, but nobody wanted to believe it. A quick sweep of the second floor and the rest of the old building only confirmed their fears.

Mike Fisher, who had worked so tirelessly to bring Bundy to Colorado to stand trial for the murder of Caryn Campbell, was slowly returning to consciousness after having had knee surgery that morning, and heard the sickening news on the television. For the time being, however, all the investigator could do was fume at the lack of attention the jailers had exhibited after he'd warned them of the very real possibility of Bundy's escape. Needing to get back in the saddle, so to speak, Fisher said his doctor discharged him "way ahead of time."'

Ironically, a court clerk had spoken earlier with Mike Fisher and Milt Blakey about Bundy, about how she believed he was planning to jump out a rear window. Apparently, Bundy had raised her suspicions, as he always insisted on copying his own paperwork, and the copier was located on the third floor of the courthouse, facing north. Nearby the copier was a window which, due to the heat in the room, was always left open. The clerk felt Bundy might try to go out this way, and could cushion his landing somewhat by hitting the awning. This hypothesis was in fact plausible. As Fisher would soon learn, Bundy did jump out of a window in the front of the building, but it was on the second floor. "She," Fisher would later explain, "was right on everything except the window."'

Feeling somewhat rested, Bundy had a new (albeit temporary) sense of confidence. Despite the hardships, the extreme exhaustion, and the rapid weight loss (he was dropping pounds a day), his only thoughts were to get away and resume the life that had been taken from him. He still believed he could make it to Crested Butte, and if he'd made the correct choices as he traversed the unfamiliar territory, he might have been successful. But Crested Butte might as well have been a million miles away. Mounting exhaustion and pain in a body that was rapidly breaking down (he was experiencing both pain and swelling in a knee and ankle), combined with a brain given to periodic flights of delusion and hallucination meant the probability of success was quickly approaching zero.

Bundy's last day in the wild was one of dodging helicopters, discovering that the cabin in which he stayed had hundreds of footprints all around it, and being confronted by an armed landowner who warned him of the dangers of being in the area because of the manhunt for Ted Bundy. He easily walked away after displaying that same charm and air of normalcy which had served him so well in politics and in murder. When Ted Bundy found himself back in Aspen on the evening of the fifth day (he'd wandered back into the outskirts of the city and almost immediately realized his mistake), he had but one route left to him, and that was to steal a car.

But for all his endless driving, and the many thousands of miles he had trolled looking for victims or disposing of their remains, his driving skillsespecially in big cars- were sadly lacking. After locating a Cadillac with the keys left under the driver's seat, Bundy had his first real chance of escape since he exited that unguarded law library through the second story window. Bundy knew the sooner he could get to Denver the better off he'd be. But the road leading east out of town was still partially blocked by the winter's avalanche and Bundy was forced to change directions.

On an otherwise quiet and virtually deserted Hwy 82, just east of Aspen around 2:00 A.M. on a Sunday morning, a patrol car, responding to a request from another unit to investigate a possible rape and/or assault, saw a blue Cadillac swerve in the street ahead, leaving the officers to believe that a drunk was at the wheel. They promptly hit their lights and siren, bringing the Caddy to a halt. Approaching the vehicle, the officers shone their flashlights into the driver's side window, and within seconds discovered two things: the driver was not inebriated and Theodore Bundy had returned to Aspen!