The Burning Shore (10 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

For the next week, U-701 struggled into the teeth of an unrelenting winter storm. Unable to reload his boat with the two deck-stored G7as, Degen realized that the rest of his patrol would likely pass with U-701 operating as “a reconnaissance and reporting unit” directing other U-boats to any Allied ships that his lookouts might spot. His next set of orders, however, suggested that Degen might have at least one more chance to sink another merchant ship. At 1337 hours on January 13, BdU ordered Degen to proceed to a designated attack area just off the southeastern coast of Newfoundland, more than six hundred nautical miles to the west-southwest. A somber Degen recorded in his diary, “My attack area still lies far away.” U-701 struggled on through the towering waves.

6

E

VEN AS

H

ORST

D

EGEN AND HIS MEN CONTINUED THEIR

storm-tossed patrol, a wolf pack of five longer-range Type IX U-boats was headed for the North American coast (a sixth, U-502, had been forced to abort its patrol due to a serious oil leak). Other lone hunters also stalked the deep of the North Atlantic, each on its own mission, each fighting to survive long enough to carry out the orders from U-boat Force Headquarters in Lorient.

One of these lone hunters, a Type VIIC U-boat, was proceeding in a westerly heading some seven hundred miles due south of Iceland—a course not unlike those of the Gruppe Ziethen boats designated to attack Allied shipping off the Newfoundland Grand Banks. However, on Wednesday, January 7, 1942, U-653 was carrying out a radically different operation on behalf of Admiral Karl Dönitz. Like his academy classmate Horst Degen, thirty-two-year-old Kapitänleutnant Gerhard Feiler was on his first wartime patrol since U-653’s formal commissioning seven months earlier. Unlike Degen, who was about two

hundred nautical miles to the northwest of U-653 and heading for Cape Race on the southeastern Newfoundland coast, Feiler had orders to remain in the central North Atlantic. For the past two weeks, Feiler’s four radiomen, working around the clock, had transmitted fake encrypted radio messages on a variety of different frequencies. Dönitz noted in the BdU

Kriegstagebüch

(daily war diary) that Feiler’s mission was “to form a radio decoy . . . which will give the impression of the presence of a large number of U-boats in the Atlantic.” U-653, a single boat, was attempting to create the electromagnetic footprint of an entire wolf pack.

The false radio gambit was one small element of a second front in the Battle of the Atlantic that remained cloaked in the highest secrecy. While the U-boats, Allied escort warships and aircraft, and embattled merchant vessels conducted their overt struggle at sea, U-653’s radiomen, together with a larger group of scientists, mathematicians, and code breakers, waged this invisible war across the electromagnetic spectrum, with most of its participants on both sides huddled in top-secret monitoring stations and other guarded facilities ashore.

The U-boat campaign against Allied shipping depended on Admiral Dönitz’s ability to send and receive secure communications between his headquarters in Lorient and U-boats at sea. When U-boat commanders operating in the open ocean reported sightings of Allied merchant convoys, BdU Operations—aware of the location of U-boats in the area from their daily position reports—could then redeploy them to intercept the merchant ships. Similarly, the code breakers at B-Dienst in Berlin gleaned the location and future course tracks of Allied convoys by intercepting and decrypting messages between the Royal Navy’s

Western Approaches Command in Liverpool and convoy escort groups at sea. The British, in turn, were running an equally ambitious cryptologic campaign against the entire German armed forces, with a particularly intense effort against encrypted U-boat communications.

In what would later be recognized as one of the great ironies of World War II, both the Germans and Allies by early 1942 had succeeded in penetrating their enemy’s most carefully guarded naval communications without the other side knowing it. When U-boats suddenly swarmed around an embattled convoy, Allied flag officers attributed the incident to chance and the Germans’ good luck rather than successful code breaking. So, too, when a series of convoys successfully evaded U-boats positioned athwart their line of advance, BdU more times than not blamed the weather or random chance for preventing German lookouts from sighting the distant masts and smoke plumes of several dozen merchantmen. The thought that one’s own encrypted communications might be open to the enemy was too painful to consider.

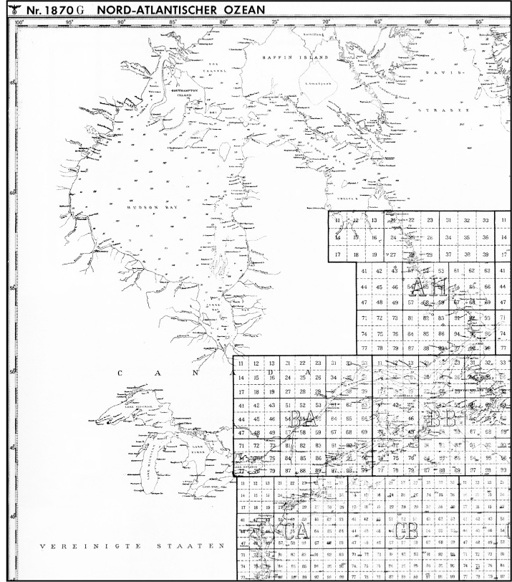

When Admiral Dönitz gathered with his operations staff at the château at Kernével Harbor on that first Wednesday in January for the daily morning conference to assess U-boat operations, Kapitänleutnant Feiler’s radio deception operation remained foremost in their thoughts. As he did on most mornings, Dönitz would have paused for several minutes to study the oversize copy of the “1870G Nord-Atlantischer Ozean” chart that hung on one wall of the operations center.

Unlike most nautical maps that relied on latitude and longitude marks to help pinpoint ship locations, the German naval chart featured a dense matrix of numbered squares covering the oceanic areas on the map. From above Iceland to the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, a series of quadrants, each identified with a two-letter code and measuring 486 nautical miles per side, marked off the trackless ocean. Inside each lettered quadrant were between sixty-eight and eighty-eight smaller squares identified by a two-digit number, measuring fifty-four miles per side. And within each of those secondary quadrants, yet another subdivision of eighty-one numbered squares marked a relatively tiny swath of ocean measuring six by six nautical miles. Ordered into effect on September 10, 1941, this was the German navy’s unique way of plotting U-boat positions, enemy contacts, and convoy routes.

The German Naval Grid system utilized a two-letter, four-number code to indicate positions of U-boats and convoys while avoiding standard latitude-longitude references that would enable Allied code breakers to penetrate BdU communications. HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM.

Rather than identifying a designated location by latitude and longitude—a recurring numerical pattern that security officials feared would facilitate enemy code-breaking efforts—the Kriegsmarine had created the German naval grid system. When a U-boat reported a convoy contact or the BdU staff issued a redeployment order to a U-boat commander, the message used the two-letter, four-number grid reference (see

naval grid chart

on p. 80). In an attempt to complicate enemy code breaking, radiomen would also encipher the grid square references themselves in a separate process to mask their true identity. Festooning the chart that Wednesday were twenty-eight pins depicting the U-boats on patrol in the North Atlantic, including the seventeen boats—U-701 among them—bound for North American coastal waters. Gerhard Feiler’s pin was affixed to grid square AL 44, nearly five hundred nautical miles south of Iceland. All but four of the U-boats headed for North America had passed to the west or southwest of U-653.

During the course of the morning staff briefings, Korvettenkapitän Günter Hessler, Dönitz’s senior operations officer, informed the admiral that Feiler would be breaking off to return to port later that day because of a low fuel state. This marked the end of a counterintelligence ploy that BdU had intended to safeguard several distinct U-boat operations in the North Atlantic. For the previous two weeks, Dönitz and his staff had hoped that Feiler would attain two objectives with his radio transmissions: the first was to alleviate British pressure on a group of U-boats operating near the Strait of Gibraltar by enticing Allied escort ships patrolling there to chase after the phantom U-boats hundreds of miles away to the northwest. The second was to mask the ongoing movement of the five Operation Drumbeat Type IXs and the twelve VIIs toward their attack areas off the North American coast. By January 7, U-125—the leading Drumbeat boat—was only nine hundred nautical miles from its assigned operating area off Long Island, New York, and the Type VIIC U-86 was just 230 nautical miles from Cape Race, Newfoundland, with the other U-boats coming up behind. Anything that could prevent the British and Americans from detecting this attack force in time and organizing a vigorous defense was critical to success in the upcoming operation. But with Feiler’s breaking off from patrol, the Germans had one less tool at their disposal.

1

T

HE CRYPTOLOGIC WAR ON BOTH SIDES OF THE

Battle of the Atlantic involved a range of advanced mathematics, theoretical research into the arcane technology of cryptologic machines,

careful analysis of intercepted messages, and a dose of covert thievery. The German penetration of Allied convoy codes occurred in several stages beginning on July 10, 1940, when the German surface raider

Atlantis

had captured the British liner

City of Baghdad

in the Indian Ocean after its crew hastily abandoned ship. A boarding team had discovered a copy of the Allied Merchant Ships Code, a two-part code used by the British Admiralty to send messages in Morse code via radio to convoys at sea. Four months later, the

Atlantis

crew seized another British freighter and found an updated copy of the code.

Within weeks of this second seizure, B-Dienst cryptanalysts were “breaking” the encrypted transmissions and providing the U-boat Force with clear-text messages from the Western Approaches Command redirecting convoys at sea away from areas of suspected U-boat activity. By early 1942, German communications experts had thoroughly penetrated the primary Royal Navy codes as well. These included the Administrative Code, Auxiliary Code, Merchant Navy Code, and Naval Code No. 1. But the most valuable success came when B-Dienst analysts began to crack Naval Cypher No. 3, a sophisticated code that the Admiralty introduced in October 1941 for the use of Allied merchant convoys and their escorts. The contents of Naval Cypher No. 3 were critical to U-boat operations since they included information about convoy departures from port. The penetration of Naval Cypher No. 3 also provided Dönitz and the BdU operations staff with the weekly top-secret British U-boat Situation Reports that apprised escort groups of known and suspected U-boat locations. These reports allowed BdU both to remove U-boats from harm’s way and to place them where least expected and thus

most deadly. Dönitz later credited the B-Dienst staff with providing him 50 percent of the operational intelligence the U-boat Force employed to hunt down Allied convoys throughout the war. Nevertheless, the intelligence windfall that the B-Dienst analysts harvested paled in comparison to the success of their British counterparts, who did what the Germans thought impossible: penetrate the secrets of the Enigma encryption machine.

2

Admiral Dönitz’s confidence in the Enigma

Marine Funkschlüssel-Maschine

was understandable. The encrypted communications system was extremely complex, and its designers were convinced that enemy decryption of tactical military messages transmitted to and from the U-boats was an impossibility. Since anyone with an antenna could intercept the high-frequency radio signals broadcast from the ground transmission station in France or a U-boat’s two-hundred-watt transmitter, it was mandatory that the U-boat Force have the means to encipher all messages in such a way that the enemy could not “break” the series of random Morse Code letters into clear text. First conceived as an encryption device for commercial use by German engineer Arthur Scherbius in 1927 (based on a Dutch engineer’s original patent he obtained), the Enigma failed to attract commercial customers but caught the eye of German military communications experts. By 1942, all of the German military services relied on variants of the Enigma machine, which had gone through numerous modifications over the previous decade. The U-boat Force at the start of 1942 utilized the M3 naval Enigma.

The battery-operated M3 Enigma device resembled an office typewriter housed in a varnished oak box with a hinged lid. It sported several strange electrical add-ons: in addition to the

twenty-six-letter keyboard, it had a flat panel on which twenty-six small circular windows were arranged in three rows, each marked with a letter of the alphabet. When the operator depressed a key, it closed an electrical circuit, and a small light bulb behind one of the windows illuminated. The letter that appeared in the lit window represented the encryption of the letter that the radio operator had just typed. The secret of Enigma lay in how the machine turned one letter—the keystroke—into a different one—the illuminated letter appearing in the circular face of one of the glow lamps—seemingly at random.

The Enigma machine used by the U-boat Force in early 1942 used three moving electromechanical rotors and a “reflector” (a nonmoving rotor) to continuously change the circuit path from keyboard to glow lamp. The Kriegsmarine provided every Enigma machine with eight different rotors, each identified with a roman numeral from I to VIII. All of the rotors identified by a particular roman numeral had identical letter-to-letter wiring designs, and the circuitry for differently numbered rotors was never the same. A U-boat officer would check a published schedule to determine which three rotors to place into the machine and the order in which to mount them on the small shaft around which they turned. The sequence of Enigma rotors installed in the machine changed every other day, adding yet another layer of complexity to the system.