The Burning Shore (14 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

The next blow came from U-123, which by the early morning hours of January 15 was closing in on the Fire Island lightship off the southern coast of Long Island, roughly midway between Montauk Point and the Verrazano Narrows entrance to New York Harbor. Task Force 15 and Convoy AT10 had not yet left the safety of the harbor, and so the waters offshore were relatively empty of US Navy warships. It was, in other words, the perfect hunting ground for Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen and his men.

Standing silently on the narrow bridge, Hardegen and his lookouts had been mesmerized for the past three hours by the bright glow on the horizon coming from the lights on Long Island. Then, as they approached the Verrazano Narrows itself, the lights from the Manhattan skyscrapers cast a blurred light on the western horizon. The sight sparked deep personal emotions for Hardegen, who, along with Horst Degen and his other Class of 1933 midshipmen, had so much enjoyed their visit to New York just nine years earlier. “I cannot describe the feeling with words,” he wrote in a German government-approved memoir the following year, “but it was unbelievably beautiful and great. . . . We were the first to be here, and for the first time in this war a German soldier looked out upon the coast of the

U.S.A.” He would recall in detail the lights of Coney Island and its giant Ferris wheel and the eerie sight of automobiles driving along the shore on Atlantic Avenue.

At 0100 Eastern War Time (EWT), Second Watch Officer Horst von Schroeter relieved Hardegen on the bridge, and the skipper went below to rest. His respite did not last long. Forty minutes later, with U-123 heading in a generally eastbound course, the lookouts called out bright lights to starboard and astern, also moving eastbound out of the Ambrose Channel. Hardegen bounded back up the conning tower ladder. With the target backlit by the city lights and showing full illumination itself, Hardegen had no difficulty identifying it. Leaning toward the voice tube, the skipper told his crew that “a big tanker” was overtaking their U-boat.

The 6,768-ton British motor tanker

Coimbra

was traveling unescorted out of New York with a 9,000-ton cargo of lubricating oil for the British Isles when a solitary G7e electric torpedo struck it on the starboard side just aft of the superstructure. Hardegen had allowed the tanker to close within eight hundred yards before First Watch Officer Rudolf Hoffmann on the

Uboot-Zieloptik

binoculars launched the torpedo. The results were catastrophic. A violent explosion sent a fireball of burning oil hundreds of feet into the dark sky, and the fiery fluid then came cascading down onto on the bridge and main deck. Within minutes, the

Coimbra

was totally engulfed in flames except at the stern. When U-123 lookouts saw crewmen hurrying aft to man a deck gun there, Hardegen ordered a coup de grâce from one of his stern tubes. Eighteen minutes after the first hit, a second torpedo struck amidships, breaking the stricken tanker in two.

Five minutes later, the broken hull sections were resting on the seabed 175 feet down, the bow, like that of

Norness

, protruding from the waves from its foremast to the stem. In a sarcastic endnote to the attack, Hardegen concluded, “These are some pretty buoys we are leaving for the Yankees in the harbor approaches as replacement for the [absent] lightships.”

2

W

ITHIN DAYS OF

U-123’

S KICKOFF OF

Operation Drumbeat, the eastern seaboard was in a state of crisis. Senior officials at the Eastern Sea Frontier in New York and Main Navy Headquarters in Washington, DC, found themselves trapped in a dual quandary: how to cope with the intensifying onslaught without sufficient ships and aircraft in hand, and what—that is, how much—to tell the American public about the sudden battle escalating just offshore. Neither problem offered a ready solution.

At first, the navy had been able to ignore the possible public-relations repercussions of the U-boat rampage. While the

Cyclops

and

Norness

had been relatively close to the East Coast when attacked, they were still far enough out at sea that no direct sign of the torpedo detonations, fires, and towering columns of smoke reached the eyes of the general population. After the loss of the

Cyclops

, naval authorities in Halifax and Washington waited two days until tersely announcing that an unidentified, 10,000-ton merchant ship had been sunk about 160 nautical miles off the coast of Nova Scotia. After U-123 torpedoed the

Norness

, no immediate alert was dispatched to American search-and-rescue units because no shore station had heard the ship’s emergency distress message. As a result, the Eastern Sea Frontier did not become aware of the attack until the US Navy dirigible

sighted the hull fragments and nearby survivors at midday on January 14. Still, a navy spokesman told reporters of the

Norness

sinking at 2300 EWT on January 14, just five hours after learning of the incident.

The sinking of the

Coimbra

changed everything. The destruction of the British tanker just twenty-seven nautical miles from the eastern Long Island beach town of Southampton sparked what can only be described as a panic-driven cover-up by the Eastern Sea Frontier and Admiral Ernest King’s headquarters in Washington. The effort was doomed to fail from the outset. The fireball from Reinhard Hardegen’s torpedoes slamming into the ship was so large and so bright that dozens of residents along the southern coast of Long Island saw the sudden plume of light offshore. They alerted local police and fire departments and the local coast guard station, and a private airplane conducting an offshore patrol found the

Coimbra

’s wreckage and the ten survivors out of a crew of forty-six British merchant seamen six hours later at 0830. Nevertheless, navy officials opted to stonewall and then to deliberately misinform the news media and public about the attack. This move to conceal the shocking failure of both the Atlantic Fleet and the Eastern Sea Frontier to deal with the U-boat threat would prove futile.

3

Following the first two sinkings along the northeastern seaboard, ESF had mounted what could best be described as a halfhearted attempt to prevent another such disaster from taking place. When the message disclosing the sinking of the

Norness

had arrived at Eastern Sea Frontier Headquarters at 1800 hours EWT on January 14, Lieutenant Commander F. W. Osburn Jr. had been serving as the command’s night duty officer. After Rear Admiral Edward C. Kalbfus, president of the Naval

War College and senior officer for naval units in Narragansett Bay, briefed Vice Admiral Adolphus Andrews on the

Norness

sinking at 12:20

A.M

. on January 15, Andrews ordered a search for the U-boat. At 0645 hours, Osburn called Floyd Bennett Field in southeast Brooklyn, where two PBY-5A Catalina flying boats were temporarily assigned, and ordered them to search the coastal waters off Long Island for “several unidentified vessels” reported to be steaming in that sector. An hour after they launched, at 0830, a third aircraft reported a “ship awash” offshore sixty-one nautical miles east-southeast of Ambrose Light at the mouth of New York Harbor. Just two hours and forty-five minutes later, the Eastern Sea Frontier staff reported that the ship in question was the

Coimbra

.

4

With the four laden troopships comprising Convoy AT10 scheduled to leave New York Harbor within hours, the navy sat tight on news of the latest U-boat attack. However, local authorities on Long Island did not. The

New York Times

documented the confusion in a front-page article that appeared the next morning, on Friday, January 16:

Breaking many hours of silence during which the Navy had refused to confirm or deny widely circulated reports of the sinking of another tanker off the South Shore of Long Island early yesterday, a spokesman for the Navy Department announced last night that a thorough check with naval and Coast Guard officials had failed to produce any confirmation of the sinking.

The details came out in any event. Chief Ross Frederico of the Quogue Police Department told a

Times

reporter that a

patrol plane had sighted ten men in a life raft floating in stormy seas several dozen miles south of the Shinnecock Inlet at around 0900. A second official, Hampton Bays Police Chief John H. Sutter, confirmed that account and added that the aircrew had seen the partially submerged wreck of the merchant ship. The reporter also learned that several coast guard vessels had raced out to the site in search of survivors of the sinking.

Navy officials in New York and Washington refused to comment on the incident for the next thirty-seven hours. It wasn’t until 1600 hours EWT on Friday, January 16, that a navy spokesman in Washington finally confirmed the sinking. He also moved the site of the U-boat attack another seventy-three miles further out to sea: “A tanker named

Coimbra

, flying the flag of a foreign ally, was observed in a sinking condition on the morning of January 15,” the unnamed spokesman said in a statement. “Its position was approximately 100 miles east of New York.” Even after the release of the statement, Admiral Andrews and the Eastern Sea Frontier continued to refuse to comment. Official navy records are silent on the rescue of

Coimbra

’s ten survivors. This would not be the last example of the US Navy feigning operational security to mask its incompetence. As the U-boats steadily escalated their attacks during the last half of January, desperate navy officials would resort to outright lies and complete fabrications to cloak the disaster at sea.

5

B

Y THE TIME

U-701

REACHED

its designated attack area east of the Avalon Peninsula on Newfoundland’s southeastern coast in the twilight dawn hours of Sunday, January 18, the Battle of the

Atlantic in Canadian waters was raging with white-hot intensity. In just six days, six U-boats—the Type IXC U-130 and the Type VII U-86, U-87, U-203, U-552, and U-553—had already destroyed nine Allied merchant ships and damaged a tenth. The total losses comprised 36,172 gross registered tons, along with the deaths of 237 Allied merchant sailors out of the 333 personnel aboard the stricken ships. Compared with the Newfoundland area attacks, the Operation Drumbeat campaign along the US East Coast was initially taking a distinct second place in targets destroyed. Thus far, only two of the Type IX U-boats had drawn blood: Hardegen’s U-123 with three kills for 25,421 gross registered tons and Korvettenkapitän Richard Zapp’s U-66 with a solitary sinking for 6,635 tons.

The first drops of blood drawn by the U-boat campaign in North American waters quickly turned into a hemorrhage: in the first three weeks, fifteen of Vice Admiral Karl Dönitz’s U-boats succeeded in destroying thirty-five Allied merchant ships and a British destroyer totaling 181,546 gross registered tons, killing 1,219 crewmen, gunners, and passengers. The toll included twelve oil tankers, twenty freighters, and the Canadian passenger liner

Lady Hawkins

, whose death toll—251 crewmen and passengers out of 306 souls aboard—was the highest for any single ship. The highest-scoring U-boats were Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen’s U-123, with eight ships totaling 49,421 tons and a ninth ship of 8,206 tons damaged; Korvettenkapitän Richard Zapp’s U-66, with five ships totaling 36,114 tons; and Korvettenkapitän Ernst Kals’s U-130, with five ships destroyed for 31,658 tons and a sixth ship totally wrecked for 6,986 tons.

Unfortunately for Horst Degen and his crew, who spent a difficult and tedious week patrolling off the Newfoundland coast from the northern tip of the Avalon Peninsula to Cape Race, U-701 did not add to its total of ships sunk. Degen had managed on January 16, during a lull in the stormy weather, to transfer his two remaining torpedoes from their topside canisters into the bow and stern torpedo rooms. However, heavy fog, snow, and ice and steady aerial reconnaissance patrols continued to thwart U-701. The boat made five attempted attacks on solitary merchant ships without success before starting the homeward transit on Saturday, January 24. The next morning, Degen sighted a westbound 5,000-ton Allied freighter that had appeared on the northern horizon at dawn, but when he fired one of his two G7a torpedoes at the merchantman, rough sea conditions caused the torpedo to run under the hull and to miss.

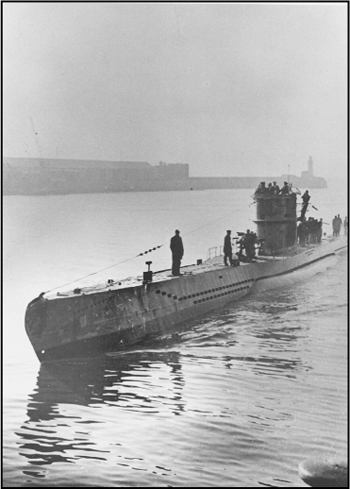

Crewmen stand atop the narrow bridge and on the main deck as U-701 returns to port in France following a North Atlantic patrol. COURTESY OF HORST DEGEN.

The return trip to the U-boat base at Saint-Nazaire passed without major incident until January 31, when BdU ordered U-701 and six other U-boats to form a search-and-rescue operation to find survivors of the 5,081-ton German blockade-runner

Spreewald

. Disguised as the Norwegian freighter

Elg

, the freighter was heading back to Bordeaux, France, when Kapitänleutnant Peter-Erich Cremer in U-333 mistakenly attacked and sank it, killing forty-eight crewmen and British merchant seamen being held on board as prisoners. U-701 and the other boats searched unsuccessfully for the next seven days for a missing lifeboat carrying twenty-four people, ultimately abandoning the effort. Passing through the lock into Saint-Nazaire’s inner harbor on Monday, February 9, U-701’s weary crew stepped ashore for the first time in forty-four days for a fifteen-day reprieve from the Battle of the Atlantic at a seaside hotel in La Baule, ten miles west of the port. In his final entry for the first patrol in U-701’s war diary, Degen noted, “Crew and boat were strongly tested on a long voyage.” And with Operation Drumbeat in full swing across the ocean, harder tests were certainly yet to come.

6