The Burning Shore (16 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

Naval Intelligence officials search the bodies of nine crewmen from the 2,438-ton collier

David H. Atwater

, which was sunk by gunfire from U-552 off Virginia’s eastern shore on the night of April 2, 1942. Hundreds of merchant sailors perished at the hands of the U-boats during the bloody campaign along the East Coast in the first half of 1942. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION.

As Winn later recounted, Rear Admiral Richard S. Edwards, King’s deputy chief of staff, was initially opposed to forming a submarine tracking room. Edwards told Winn that the US Navy wished to learn its own lessons and had plenty of ships with which to do so. At that point, the mild British lawyer-turned-U-boat-hunter blew his stack. “The trouble is, admiral, it’s not only your bloody ships you are losing,” Winn heatedly replied. “A lot of them are ours!” This was no exaggeration on the OIC official’s part. Out of 216 Allied merchant ships sunk by the U-boats in North American coastal waters and the Caribbean between January and mid-April 1942, 98 were operating with the British Merchant Navy—51 flying the Union Jack and another 47 from Nazi-occupied countries that had joined the Allied cause—some 45 percent of the overall total. US-flagged losses came in a close second, with ninety ships sunk during that same period. Admiral King in a subsequent meeting agreed with Winn and told the British officer that the US Navy would create its own submarine tracking room. However, other measures—notably a coastal convoy system—would take much longer to implement.

The carnage offshore continued without letup, but Horst Degen and Harry Kane were not among the participants in this escalating battle. The happenstance of war had sent them on quite different adventures elsewhere: Degen and U-701 to patrol off Iceland, Kane and his aircrew to more training flights along the West Coast. At this juncture, Harry Kane and his men—and not Horst Degen and his crew—would experience one of the more bizarre encounters of the war.

4

T

HE ATTACK BEGAN SHORTLY BEFORE SUNSET

on February 23, 1942. Commander Kozo Nishino brought the 2,584-ton Japanese cruiser submarine I-17 inshore west of Santa Barbara, California, then ordered his ninety-three-man crew to surface and his gun crew to arm the 144-mm (5.5-inch) deck cannon. As I-17 loitered less than two hundred yards from the beach, its gunners began firing at the giant Bankline Company aviation fuel storage farm on the bluffs overlooking the shore. During the next twenty minutes, I-17 lobbed seventeen shells, each weighing eighty-four pounds, at the sprawling facility. Most shots went wild, and only one shell landed within thirty yards of one of the storage tanks. After his last shells had either splashed into the Santa Barbara Channel or plowed into empty land behind the fuel farm, Nishino then ordered I-17 back out to sea.

The Japanese attack was risky and audacious but militarily ineffective. Its psychological shock value, however, was profound: for the first time since the war began eleven weeks earlier, an Axis warship had bombarded the US mainland. This threw the entire West Coast population into a state of near hysteria. The next morning, a headline that could be read with

the naked eye from one hundred yards away dominated the

San Francisco Chronicle

’s front page: “SUB SHELLS CALIFORNIA! War Strikes California: Big Raider Fires on Oil Refinery 8 Miles North of Santa Barbara.” The

Los Angeles Times

headline was equally shrill: “ARMY SAYS ALARM REAL: Roaring Guns Mark Blackout.” The Fourth Army went on alert from San Luis Obispo to the Mexican border. Public fears of a possible Japanese carrier air attack or even invasion along the West Coast—concerns that had subsided slightly in the twelve weeks since Pearl Harbor—now spiked anew.

The US Army had not been idle on the West Coast since the December 7 Japanese attack. At the outbreak of war, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, as Fourth Army commander, had eleven infantry and five antiaircraft artillery regiments throughout the region, although most units lacked two-thirds of their allotted equipment. In the first weeks after Pearl Harbor, the army rushed reinforcements to vital parts of California, Oregon, and Washington state. By early February 1942, DeWitt commanded six infantry divisions, a cavalry brigade, and fourteen antiaircraft artillery regiments. Of nearly 250,000 army troops based in the Fourth Army area of responsibility, more than 100,000 manned antiaircraft batteries that ringed dozens of vital military bases, harbors, and defense plants. In the early evening hours of February 24, 1942, they were still on full alert some twenty-four hours after I-17 opened fire on the Bankline fuel farm. Within the next five hours, Lieutenant Harry Kane and his aircrew would inadvertently douse the fire with gasoline.

5

It was supposed to be a routine training mission, Kane recalled years later. By now, his squadron had grown to twenty-two officers and 225 enlisted men. Many of them were newcomers

and required extensive individual training in their aircrew roles. “At one time we got a whole batch of new navigators into the squadron and we had to take them all out and give them some real tough training,” Kane said. Training for these new navigators often took the form of long coastal patrol flights, which—as Kane soon discovered—could quickly turn deadly, given the paranoia about enemy forces operating in the same areas.

On the evening of February 24, Kane took off from Sacramento with a full crew, including a newly assigned navigator lieutenant. The flight plan called for Kane to fly out two hundred miles due west from San Francisco, then turn to follow a southerly course for about 360 miles, which would place them out over the Pacific due west of Los Angeles. At that juncture, the navigator would have to calculate the moment at which Kane should turn the aircraft to a heading of 074 degrees to fly straight in to land at March Field, located some sixty-five miles east of Los Angeles near Riverside. The plotted course would also bring Kane’s aircraft in over Los Angeles itself, flying close over the Long Beach Naval Station and Naval Shipyard and numerous defense plants, including the Douglas Aircraft factories in Santa Monica and Long Beach and the Lockheed factory near Burbank.

The first three hours of the flight passed without incident. After turning at the two-hundred-mile point west of San Francisco, Kane and his crew flew the southbound leg for just under two hours when the lieutenant announced that it was time to turn to the heading of 074 degrees and proceed toward the Southern California shoreline about four hundred miles away. At about 7:30

P.M

., Kane noticed that the sky was darkening from a thick cloud bank that lay ahead of the aircraft. He decided to take radio

direction-finding fixes on Los Angeles and San Diego radio stations as a backstop for the navigator’s calculation. At that point, Kane discovered that all of the stations were off the air. He tried descending below the cloud layer to get a visual sighting of the coast but abandoned the effort when a crewman fearful of crashing into one of the Channel Islands started screaming for him to pull up. As they neared the coast, the cloud bank cleared up, to the aircrew’s relief.

Two hours later, Kane and crew found themselves orbiting above March Field, delighted that the navigator’s fix had been so accurate. Then a voice from the control tower suddenly called out in his headset, “Lieutenant Kane, you are requested to land at March Field as soon as possible. The general wants to see you.” Kane turned to his navigator with a puzzled look on his face. Normal procedure was for ground control to call an aircraft by its tail number, but they had asked for him by name. Minutes after landing and taxiing the aircraft to its parking spot, Kane found himself braced at attention while a furious Major General Jacob E. Fickel chewed him out.

“You stupid blankety, blank, blank, do you realize what’s happened?” Kane remembered the Fourth Air Force commanding general barking.

“No sir,” Kane said.

“You were an unidentified aircraft and you have blacked out all of Los Angeles and all of San Diego and put the radios in both places off the air, and I have sent four P-38’s up looking for you with instructions to shoot you down!”

Unbeknownst to Lieutenant Kane and his aircrew, US Army Air Forces officials in Sacramento had forgotten to inform their counterparts at March Field of the long-range navigational

exercise that Kane and crew were conducting. Sometime between Kane’s turn to 074 degrees and the aircraft’s approach to the Los Angeles shoreline, an army radar set picked up what its operators concluded was an unidentified aircraft heading in from the open ocean. No doubt exhausted and stressed from the previous day’s alert following I-17’s bombardment of the Bankline fuel farm, the radar operators and antiaircraft gunners likely concluded that Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s carrier fleet had returned to attack Southern California. Army gunners went to their antiaircraft batteries, and civil defense officials ordered a total blackout from San Luis Obispo to the Mexican border, including the radio stations. And then—several hours after Kane and his crew landed safely at March Field—all hell broke loose.

At 0222 hours Pacific War Time, the night skies from Santa Monica to Long Beach thirty miles away suddenly erupted with brightly illuminated searchlights and long, fiery streams of antiaircraft tracers. It was the start of a five-hour mass panic that resulted in three deaths, dozens of injuries, and widespread property damage. One news report later described the spectacle as “the first real show of the Second World War on the United States mainland.” Calls from frightened residents claiming to have seen anywhere from several dozen to more than one hundred aircraft flying overhead inundated police and fire stations. Since the blackout regulations required motorists to extinguish their headlights and pull over to the side of the street, the roads and highways quickly became gridlocked, especially since tens of thousands of defense workers were heading to or from their shifts.

But the antiaircraft (AA) shells, not the public panic, did the real damage. Army officials subsequently reported that 1,430 AA rounds were fired during the ordeal. With no aircraft overhead to strike, the explosive shells soared high into the sky and then fell all over Los Angeles. Shrapnel slammed into the municipal airport, broke windows of the Long Beach branch of the Bank of America, and forced overnight shipyard workers in Long Beach to dive under their equipment for safety. Dr. Franklin W. Stewart and his wife were at home when a 3-inch AA shell crashed through the roof and exploded in a home office, destroying the room and the family kitchen but leaving them unharmed. City resident Victor L. Norman was not in his bedroom when a shell burst through the ceiling, which was fortunate for him. The detonation shredded everything in the room into small pieces. Two motorists died in collisions with other vehicles, and a California state guardsman driving a truck full of AA ammunition suffered a fatal heart attack.

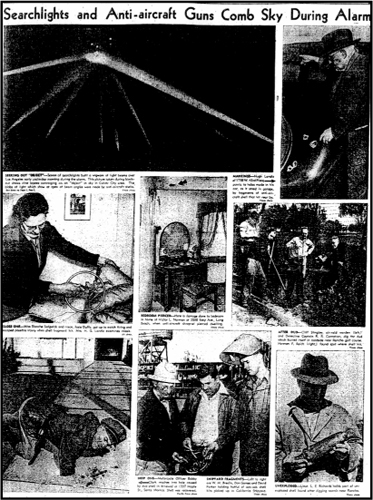

In the aftermath of a Japanese submarine’s shelling of a Southern California oil farm, edgy antiaircraft gunners filled the night skies over Los Angeles with searchlights and gunfire shortly after Lieutenant Harry Kane and his aircrew made an unannounced flight over the city. The mass panic was caught by newspaper photographers. COPYRIGHT © 1942,

LOS ANGELES TIMES

, REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION.

The night of mayhem came to be called the “Battle of Los Angeles,” and very few people knew then (nor do they now) that it was indirectly caused by Kane’s flyover—or, more accurately, the USAAF officials who had mismanaged it. Given the widespread paranoia among many Californians about the threat of sabotage and subversion from Japanese Americans—aliens and citizens alike—many members of the public were quick to accuse the Japanese of carrying out the mysterious aircraft flights or guiding them from the ground. Since the federal government had already begun its plan to evacuate over 110,000 Japanese Americans to internment camps, local and federal authorities announced the arrests of twenty of them in connection with the incident. Nor was that the end of it. The confusion and paranoia quickly spread from Los Angeles to Washington, DC.

Garbage in, garbage out: relying on local reports from the chaotic scene, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson announced on Thursday, February 26, that the incident had involved fifteen mysterious aircraft flying at altitudes ranging from 9,000 to 18,000 feet. “It seems reasonable to conclude that if unidentified planes were involved, they may have come from commercial services

operated by enemy agents” seeking to discover the location of antiaircraft batteries, he intoned. Navy Secretary Frank Knox disagreed, flatly dismissing the whole affair as “a false alarm.” General DeWitt made the best of a bad situation, publicly commending the antiaircraft gunners, pursuit squadrons, civil defense wardens, and everyone else who had played a part in the debacle.

6

The originators of the panic, meanwhile, were long gone. When Major General Fickel—the officer who had chewed Kane out upon his landing—and his senior staff realized that the error stemmed from USAAF Headquarters in Northern California, they quietly let Kane off the hook, and he and his aircrew flew back to Sacramento the day after the incident. By the time of Stimson’s announcement, Kane and his aircrew had resumed their training at Sacramento Municipal Airport, largely unaware of the chaos and excitement they had so innocently sparked.