The Burning Shore (21 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

W

HILE

D

EGEN AND HIS CREW CONCENTRATED

on the routine day-to-day tasks of their westward passage in the first days of June, senior American admirals in Washington, DC, and Honolulu were grappling with a sudden major crisis in the Pacific. An imperial Japanese naval force of four aircraft carriers, 181 surface warships and auxiliaries, and several dozen submarines was steaming across the central Pacific to attack and occupy Midway Island, about 1,000 miles northwest of Hawaii. Elements of the Japanese fleet also planned a diversionary attack against US bases in the Aleutians. The US Pacific Fleet, still struggling to recover from the Pearl Harbor disaster, could assemble only three carriers and twenty-five surface escorts to block the Japanese. However, Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz had one advantage that would prove pivotal. A team of navy code breakers had gleaned enough intelligence from decrypted Japanese naval messages to position the carriers

USS Enterprise

,

USS Hornet

, and

USS Yorktown

in place for an ambush against the four aircraft carriers headed for Midway.

Despite the navy’s firm intelligence about the destination of the larger Japanese force, army leaders continued to fear that it would steam past Hawaii to strike the West Coast. As it turned out, though, the code breakers were correct. During four days of fighting between June 4 and 7, the Americans sank all four Japanese carriers and a cruiser and destroyed 248 carrier aircraft and their aircrews. American losses were smaller: the carrier

Yorktown

, a destroyer, and about 150 aircraft. Victory at Midway allowed the US Pacific Fleet to seize the strategic initiative in the Pacific.

The consequences of the American victory at Midway were far-reaching. The battered Japanese fleet, having lost four of the six carriers that attacked Pearl Harbor, limped back to Japan; Americans everywhere—when details of the victory emerged weeks later—had the opportunity to celebrate for the first time since December 7, 1941. Victory at Midway also cleared the path for Nimitz and Admiral Ernest King to take the offensive in the Pacific. In August 1942, the Marine Corps would land on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, marking the first major American land offensive against Japan and beginning the steady rollback of Japanese advances in the Pacific.

One unnoticed and unheralded event that stemmed from the Pacific Fleet victory at Midway would have a direct and dramatic impact on U-701 and its men. With Japanese forces now tied up in the Pacific, on Monday, June 8, General DeWitt canceled the special alert triggered by fears of a Japanese attack, and the War Department began recalling the extra units it had rushed to the West Coast. At the same time, redeployment orders came down from Fourth Air Force Headquarters to Lieutenant Colonel D. O. Monteigh, commander of the 396th Medium Bombardment

Squadron. On Saturday, June 12, the squadron base at Sacramento was a beehive of activity. Monteigh had received orders to lead a cadre of thirty-four officers, fifty-five enlisted men, and all fifteen of his squadron’s A-29 Hudson bombers on a cross-country aerial caravan to eastern North Carolina starting the next day. Upon arrival at the Marine Corps air station at Cherry Point, their new mission would be to hunt for German U-boats.

8

U-701’

S CREW WENT TO BATTLE STATIONS

shortly before sunset on Friday, June 12, but the men had been on edge since long before that point. They had been on full alert for the past four days, as U-701 slowly crept into American waters and came within range of land-based patrol bombers. The radio operators had entertained the crew by piping American radio broadcasts through the boat’s internal loudspeakers. To great amusement, they heard several news reports announcing that Sunday, June 14, had been proclaimed “MacArthur Day,” honoring General Douglas MacArthur on the forty-third anniversary of his appointment to West Point. Crewmen joked that their present to MacArthur would be fifteen magnetic mines.

On the U-boat’s cramped bridge, however, the mood remained deadly serious. The duty watch officer and three enlisted lookouts took particular pains to scan their sectors of the horizon for any American warships or patrol planes. To their astonishment, the ocean and skies remained empty. “There were no airplanes and no coast guard cutters as U-701 drew nearer and nearer to the shore,” Degen later recalled.

Then, suddenly, U-701 arrived. Several hours after dark on June 12, the bright lights of the Cape Henry and Cape Charles

lighthouses rose above the western horizon, clearly marking the twenty-nautical-mile opening between the Virginia Beach shoreline and the southern tip of the Delmarva Peninsula.

Earlier in their journey, Degen, Leutnant zur See Erwin Batzies, Obersteuermann Günter Kunert, and Oberleutnant zur See Konrad Junker had spent hours reviewing a large nautical chart of the area. They came to two firm conclusions. First, the wide waterway separating the two capes was an illusion. “The chart clearly showed us that there was only one way into the gate . . . due to a big [underwater] bank that came down from Cape Charles,” Degen explained years later. “It covered the direct westward entrance from the Atlantic into Chesapeake Bay.” The chart showed that ships entering the bay had to round the shallow bank at its southern tip, then proceed north paralleling the Virginia Beach shoreline in order to reach the entrance to the dredged ship channel. Second, they would ignore the BdU operations order for the mine-laying mission. “Our operations order directed us to go straight to the entrance of [the Chesapeake] Bay; to dive there during the night and to observe during the day the exact ship traffic of incoming and outgoing ships,” Degen wrote. But that meant U-701 would have to hide in water adjoining the dredged channel only thirty-six feet deep, leaving its conning tower just four feet below the surface. Dismissing the staff order as “suicidal,” Degen opted to run straight into the channel after midnight, locate the ship channel through visual observation, drop the fifteen TMB mines, and get the hell back out. The only flaw in their new plan was a development neither they nor Admiral Dönitz knew about: the Eastern Sea Frontier already knew that several U-boats were on their way to the US East Coast to lay minefields.

9

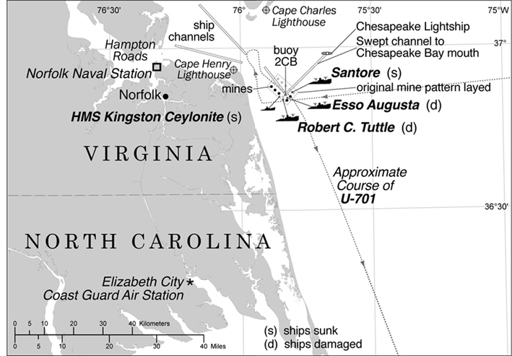

U-701’s mine-laying operation at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay required the U-boat to come within several hundred yards of shore on the surface before it reached the target area. ILLUSTRATION BY ROBERT E. PRATT.

T

HE FIRST WARNING

that the Germans had decided on a mine-laying campaign in American coastal waters had come in April, when an agent working for US Army Intelligence in France revealed that BdU had initially decided to block American seaports during March. Vice Admiral Andrews at ESF Headquarters received a copy of the agent’s report, which included “surprisingly detailed [map] overlays of the [proposed] minefields.” Since the agent’s previous reports had usually turned out to be accurate, the navy and Andrews’s ESF staff took the threat seriously. However, April and May passed without incident.

Then came the next alert. On Tuesday, June 9, COMINCH issued a warning to all US Navy commands on the East Coast that a reliable intelligence report revealed that BdU had recently received a large supply of antiship mines. The following day, a third piece of intelligence seemed to confirm the German mine-laying threat beyond any doubt. In Santiago, Chile, a high-ranking official of the Chilean shipping line Compañía Sud Americana de Vapores tipped off the US embassy that the German ambassador had warned that country’s foreign minister to keep all Chilean vessels away from New York Harbor because it would be mined in the very near future.

At his headquarters in lower Manhattan, Vice Admiral Andrews ordered an alert message sent out to all ports, naval districts, and operating units under his command. Beyond this, however, the Atlantic Fleet could only watch and wait.

10

D

EGEN HELD

U-701 several miles off the coast until around midnight, then ordered the boat slowly ahead to close with the

shoreline. Because the two lighthouses remained illuminated, the task of locating the entrance to Thimble Shoal Channel became nearly effortless. Kunert, the navigator, was on the conning tower bridge with Degen, Junker, and Batzies. His task was to take constant bearings of the Cape Charles Lighthouse. When the flashing light showed a bearing of due north, U-701 would turn ninety degrees to starboard, heading directly for the target area at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

U-701 continued moving slowly westward toward the Virginia Beach shoreline for nearly an hour, aiming for a point of approach about five miles south of Cape Henry. “Besides our echo-sounding, we kept a sharp eye for Cape Charles and its guiding light,” Degen recalled. Finally, Kunert called out that Cape Charles was bearing due north, and Degen ordered the starboard turn. The U-boat, with its diesel engines murmuring softly, came around until it was running parallel to the shoreline. Six months earlier, Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen and his lookouts on U-123 had gaped at the busy nighttime traffic along Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue at the opening of Operation Drumbeat. Despite the ravages the U-boats had inflicted on Allied shipping along the US East Coast since then, Degen and his team were seeing the same “breathtaking” spectacle, he later recounted. “To the port we could see the dark shadows of dunes, with lights here and there . . . even cars and people and lighted houses. These Americans didn’t seem to know there was a war going on!”

As the Cape Henry Lighthouse drew near, Degen knew that U-701 was very close to the channel entrance. He ordered the maneuvering watch to bring the boat’s speed to dead slow and

the torpedo mechanics to prepare to drop the mines. In the bow compartment, the torpedomen flooded the four torpedo tubes and opened the bow cap of the first tube. Then they released the locking bolt that anchored the forward-most TMB mine in that tube.

Degen was about to give the order to release the first mine when several lookouts stiffened. A small patrol boat was crossing the 1,000-foot-wide ship channel dead ahead of U-701. The vessel was totally blacked out, but the illumination from the shore cast enough light for the lookouts’ night binoculars to spot it without difficulty. Degen and the others watched as the patrol boat reached the western side of the channel, then reversed course and headed east, passing from left to right just several hundred yards ahead. Degen ordered his helmsman to bear to the left for the western edge of Thimble Shoal Channel. Glancing at his watch, he saw that it was 0130 local time on Saturday, June 13. He spoke into the voice tube, and a jolt of compressed air ejected the first TMB mine out of the torpedo tube. It silently fell to the bottom of the channel fifty-two feet down.

For the next fifteen minutes, U-701 slowly zigzagged along the western side of the ship channel, dropping a mine every two minutes. Degen and the other lookouts did not let the patrol boat out of their sight. As the little patrol craft reached the middle of the channel again heading west, U-701 had laid seven of the fifteen mines. Degen then ordered the engine room to shut down the diesel engines and activate the silent e-motors. U-701 drew past the patrol boat’s track and moved another hundred yards up the channel. Then Degen ordered a reverse course and began to zigzag along the eastern side of the channel. The boat

slowly moved back toward the open ocean, dropping the remaining eight mines as it proceeded. When the last mine fell out of U-701’s stern tube, Degen’s watch read 0200 hours local. The mines were set, their internal clocks ticking off the preset sixty-hour interval before they armed themselves. It had taken just half an hour to do the job. U-701 silently moved back out into the Atlantic Ocean and headed south at high speed for its patrol area off Cape Hatteras.

11

W

HILE

U-701

WAS DROPPING ITS MINES

in the vicinity of the whistle buoy “2CB” that marked the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, three other U-boats were engaged in equally dangerous inshore moves farther north. U-87 came in between Cape Henlopen, Delaware, and Cape May, New Jersey, that same moonless night and dropped fifteen TMB mines across the Delaware Bay channel. At the same time, U-373 edged into the shallow waters of Massachusetts Bay to block the ship channel at Boston. Both laid their minefields without detection.

Things went differently for the third boat, U-202, which barely avoided disaster. Departing Brest on Wednesday, May 27, Degen’s close friend and classmate Kapitänleutnant Hans-Heinz Linder proceeded to Lorient, where four Abwehr agents, including thirty-nine-year-old team leader George John Dasch, boarded the U-boat. The team brought with them four small crates packed with TNT and other explosives, timers, and detonators. Fifteen days after leaving Lorient, late in the evening of June 12, U-202 crept through a thick fogbank toward the landing site on the eastern end of Long Island. Linder and his lookouts

were peering through a thick fog and listening to the sound of waves breaking on the beach when U-202 touched bottom and grounded. Two sailors and the four saboteurs with their deadly cargo set out for the beach in an inflatable dinghy. After long minutes of struggling against the surf, the men reached the shore, leaped out into waist-deep water, and waded ashore. Linder and his lookouts were so preoccupied with landing the Abwehr team that they failed to notice U-202 had swung parallel to the beach as the tide went out. At last, however, the two sailors who had ferried the agents ashore signaled to U-202, and other crewmen hauled them back to the boat via a towline. What they reported to Linder threw the U-boat commander into a panic: a US Coast Guard patrolman had stumbled on Dasch and his team as they were burying the explosives. Discovery of U-202 by the Americans seemed inevitable. Fortunately, after two hours of terrified waiting, a miracle occurred. The tide shifted and was now coming back in. Linder sent every off-duty crewman to the stern to lighten up the bow, then put full power into both diesel engines and the two e-motors. U-202 suddenly broke free of the sand and began backing out into deep water. The crew erupted in cheers.

12