The Burning Shore (29 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

W

HILE THE

B

ATTLE OF THE

A

TLANTIC

was over for Kane and the 396th Medium Bombardment Squadron, and while the war itself was over for Horst Degen and his men, the deadly fight between the U-boat Force and Allied merchant shipping steadily escalated out in the open ocean. During the six-month campaign along the US East Coast, in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, and along South America’s northern shoreline, Admiral Dönitz and the BdU staff could deploy on average only fifty-one U-boats on any given day. With the coming of spring and summer, the logjam of newly commissioned U-boats trapped in the Baltic ice during the fierce winter of 1941–1942 finally broke up, and the U-boat Force steadily grew in size. The daily at-sea average surpassed 100 boats in September 1942 and would peak at 118 by mid-1943.

The next phase of the Battle of the Atlantic occurred in late 1942 as Dönitz unleashed dozens of U-boat wolf packs across the North Atlantic convoy routes between North America and the British Isles. With the British code breakers still shut out of the four-rotor naval Enigma communications system, and with B-Dienst cryptologists in Berlin regularly breaking Allied merchant and naval codes, the U-boats enjoyed a distinct advantage in the race between the two sides’ intelligence services to anticipate, locate, and destroy the enemy at sea. Merchant ship losses soared in the last four months of 1942: worldwide, the U-boats sank 96 ships totaling 461,794 gross tons in September, 89 ships for 583,690 gross tons in October, and 126 vessels comprising 802,160 gross tons in November. The tally for December through February 1943 showed a marked decline, but only because the fierce winter storms during that three-month period halted the fight on both sides. The coming of spring in 1943 brought a resumption of the conflict in all its fury and a full-fledged crisis in Washington, London, and Ottawa as Allied leaders feared the possibility of an outright German victory at sea. Still, one positive development for the Allies occurred in December 1942. Bletchley Park finally broke back into German naval Enigma. This set the stage for a renewed stream of intelligence data that would enable the Allies to locate the U-boats, muster their defenses against them, and ultimately prevail at sea.

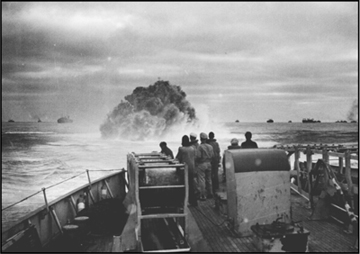

After the US Navy organized an effective coastal convoy system along the East Coast in late spring 1942, the U-boat Force shifted operations back to the deep North Atlantic and set the stage for the ultimate Allied victory in the spring of 1943. Here, the coast guard cutter

USS (CG) Spencer

, on April 17, 1943, has attacked and sunk the Type IXC U-175 with depth charges within sight of Convoy HX233 south of Iceland. CLAY BLAIR COLLECTION, AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING.

The stunning Allied turnaround against the U-boats culminated in a series of convoy battle victories in May 1943, which destroyed forty U-boats in that month alone and forced Admiral Dönitz to withdraw his forces from the North Atlantic. This retreat set the stage for a successful Allied invasion of Western Europe the following year. Made possible by the uninterrupted flow of men and matériel across the Atlantic, the Allies’ invasion of Normandy and the eleven-month land campaign that followed broke the Nazi regime and forced its unconditional surrender.

*

For the U-boat crews who enjoyed

der Glückliche Zeit

in North American waters during the first six months of 1942, the succeeding phases of the Battle of the Atlantic would bring a crushing string of defeats. After the decisive battles that forced the U-boats out of the transatlantic convoy routes, Admiral Dönitz made several attempts to employ new weapons and technologies to offset the U-boats’ deepening inferiority to Allied defenses. All failed: within a few weeks the Allies neutralized a new wake-homing torpedo designed to sink convoy escort warships; a U-boat “snorkel” that allowed the air-breathing diesel engines to run while submerged rendered the boats too slow to

operate effectively; and the introduction of two new high-speed U-boat designs came too little, too late to have any significant impact on the war at sea. By late 1944, the once-feared German U-boat Force had been driven back into the Baltic and Norwegian fiords with the Allied liberation of France and the loss of the Brittany ports.

Even with all of these setbacks, there was no letup for the battle-scarred German U-boat crews. Officially volunteers fighting for a regime that tolerated no dissent, they were in it for the duration. As the Battle of the Atlantic dragged on for nearly another three years after the campaign along the East Coast ended, U-boat service became for most crewmen a death sentence. Of the 4,631 German U-boat men who served aboard the ninety-five U-boats involved in the North American campaign, 3,479 officers and enlisted men—75 percent—were killed at sea. Of the 1,152 survivors, 249, or 22 percent, were rescued by their attackers and spent the rest of the war as POWs. Only 903 officers and enlisted men would survive and return home to Germany to see the final collapse of the Third Reich. Only nine of those ninety-five U-boats avoided destruction at sea: three were rendered ineffective after being bombed in port, another four were scuttled in port to avoid capture by the Allies, and the ill-fated U-505 was captured by a US Navy hunter-killer group west of Africa on June 4, 1944. Only one U-boat, U-155, was still operating at sea on May 5, 1945, when it received Admiral Dönitz’s order—by that time he had succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state—to surrender to the Allies.

Like their German U-boat enemies lurking off the North Carolina Outer Banks, the men of the 396th Medium Bombardment

Squadron found that there remained much more of the war to fight after their temporary East Coast assignment. In early December 1942, the squadron transitioned to the B-25D Mitchell bomber and spent much of 1943 conducting practice combat missions in the new aircraft. In late October 1943, the unit transferred to Hawaii, and by Christmas Eve it was operating out of an airstrip at the former Japanese bastion of Tarawa in the central Pacific, captured by the Second Marine Division just four weeks earlier. During the first four months of 1944, the squadron flew multiple raids against Japanese bases in the Marshall Islands about five hundred miles away. The unit—whose personnel strength by then was about four hundred men—suffered fifty combat fatalities and another thirty-eight men wounded in action during that period. As the US military ground its way across the Pacific toward the Japanese homeland in 1944–1945, the squadron followed and, at war’s end, was operating out of the Philippines.

6

After his discharge from the US Army Air Forces in late 1945, Harry and Marguerite Kane settled in her hometown of Kinston, North Carolina. The war had transformed the sleepy tobacco and cotton trading center into a modern American city. What Kane had jokingly called a “desolate country” in mid-1942 was now thriving due to new manufacturing plants and the proximity of a major military air base. Kane founded the Coastal Plains Distribution Company in Kinston and became an active member of the local business community. In the years immediately after the war, they had three children, Harry III, Randy, and Marguerite. They became socially prominent members of the community, joining several clubs and organizations. During the summer, they could stay at the LaRoque family beach house at Atlantic Beach near Morehead City.

7

H

ORST

D

EGEN

’

S HOMECOMING

could not have been more different from that of American servicemen returning from the war. Traveling by train across the United States, then by ship to a resettlement camp near Hamburg, he came home in June 1946 to a devastated Germany with millions of people dead or missing. Allied bombing, including a 1943 raid that triggered a firestorm that killed at least 42,000 civilians in one night, had devastated his new hometown of Hamburg. But Degen did not wait to resume his life. Within a week of his release at Hamburg on June 6, 1946, Horst met and quickly proposed to Lotte Dressler, the thirty-year-old widow of a German officer who had died on the Russian front in 1943. He became stepfather to her two young sons, Rolf and Rainer, and in 1948 they had a son of their own, Günther. For several years, Horst managed his wife’s family’s business, a fifty-eight-year-old wine and spirits wholesaler in the city of Lüneberg outside Hamburg. After the family sold the company in 1964, Degen joined a local Ford Motor Company dealership and enjoyed a full career as its administrative manager, retiring in 1978. Horst Degen did not discuss his wartime experiences with his family, preferring to put that dark chapter of his life behind him. But it would not stay buried forever.

8

On a warm evening in late May 1968, Horst Degen was watching the evening news on TV at home with his son, Günther, when a news bulletin ripped through his heart like a dagger. The news anchor reported that American naval ships involved in a frantic search for the missing nuclear attack submarine

USS Scorpion

had come across what some believed was the wreck of a German U-boat. The US Navy announced that another nuclear submarine had found the submerged hull in about 180 feet

of water. At the time, Degen recollected U-701 as having gone down in about 200 feet of water (not the actual depth of 110 feet as later determined), and his initial reaction was that the US Navy had found his U-boat. He later recounted his reaction to a local magazine reporter. “For a moment, I was stunned. Then my son, who was sitting next to me, heard me murmur, ‘Son, that could be my boat.’ And suddenly I again was living through . . . the two most horrible days of my life and the two darkest nights.” Details he had long suppressed now flooded Degen’s mind: the depth charges splitting open U-701’s pressure hull, the desperate swim up to the surface, early hopes of rescue that faded into endless hours clinging to the flotation devices, watching his shipmates descend into madness or quietly give up and slip under the waves, and the unexpected miracle of rescue. With those long-buried memories free once more, Degen sat down and penned a thoughtful letter of condolence to the US Navy for the loss of its shipmates—an experience whose horrors few others could comprehend as well as he. Several months later, the US Navy announced that the mysterious wreck was not a U-boat but the capsized hull of a freighter that had fallen victim to a U-boat.

9

A

NEWS STORY OF AN ENTIRELY DIFFERENT

stripe triggered wartime memories for Harry Kane. In the fall of 1979, the sixty-one-year-old businessman came upon an account of sport scuba divers who liked to explore two submerged U-boat wrecks off the North Carolina coast. Discovery of the hulk of U-85 about forty-four nautical miles north-northeast of Cape Hatteras and

U-352 only fifteen nautical miles south of Cape Lookout got Kane to wondering, Why hasn’t anyone found the wreck site of U-701? After requests for information from the US Naval Historical Center drew a blank, Kane became interested in seeing if he could locate the U-boat himself. He decided that he should seek out its former commander for any information or insights that might help. After several unsuccessful attempts through the German Red Cross and a German military veterans organization, in October 1979 Kane wrote a letter to the editor of the

Hamburger Abendblatt

seeking the newspaper’s help in locating Horst Degen. To Kane’s great surprise and pleasure, the newspaper found Degen and gave him Kane’s address in North Carolina. Thirty-seven years after their confrontation at sea, the two veterans began a lengthy and engaging correspondence.

Degen and Kane avidly shared details of their encounter that the other did not know about and exchanged photos, documents, and holiday gifts. Kane explained that his success in surprising U-701 on the surface was due to his deliberate violation of USAAF tactical doctrine to fly at an altitude of just one hundred feet above the surface of the ocean. In a follow-up letter, Kane revealed that his A-29 was nearly out of fuel when reaching Cherry Point after hours of trying to attract rescue ships to the scene. “If anyone ever mentions to you that I did not stay [over the water] as long as possible trying to find you again, don’t believe them,” Kane wrote. Degen in turn was candid about the fatal role that his “drowsy” first watch officer played in letting the A-29 sneak up on U-701. “If we had dived three minutes earlier, you wouldn’t have got us,” Degen wrote. After Degen mailed Kane a copy of his unpublished 1965 memoir of U-701’s

last patrol, Kane replied that he had realized an “absolutely fascinating” fact. Both he and Degen had traveled a total of 6,000 miles—Kane from California and Degen from France—to reach the scene of their fateful engagement, and they had arrived within hours of one another in mid-June 1942.

Early on in their correspondence, Degen apologized to Kane for the gushing tone that the Hamburg newspaper had taken in an article recounting the meeting between the U-boat commander and army pilot at the Norfolk Naval Hospital on July 11, 1942. “I would like to bring to your attention the somewhat funny article in the

Hamburger Abendblatt

concerning the great ‘friendship’ between you and me!” Degen wrote. “I was a little embarrassed. It sounds as if we both had become friends in a way that would not be so very correct in wartime.” Nevertheless, as the two men continued their correspondence in the winter of 1979–1980, their interest in one another’s accounts grew stronger. Often Kane or Degen could not wait for the reply from his most recent letter and would dash off another update. By the spring of 1980, the two veterans had indeed become fast friends. Harry Kane was more determined than ever to find U-701, and that year he found a group of scientists with the knowledge, equipment, and interest in naval history to make the search possible.

10