The Burning Shore (30 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

S

IX YEARS BEFORE

H

ARRY

K

ANE

tracked down Horst Degen at his home in West Germany to solicit his help finding U-701, a fellow North Carolinian had made an unprecedented underwater discovery not far from where the U-boat went down. Dr. John

G. Newton, superintendent of the Duke University Marine Laboratory, led a team that included Dr. Harold “Doc” Edgerton of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Gordon P. Watts Jr., then an underwater archeologist with the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. They were searching for the Union ironclad

USS Monitor

, which had foundered off Cape Hatteras on December 31, 1862, nine months after its historic “battle of the ironclads” with the Confederate warship

CSS Virginia

in Hampton Roads. Using state-of-the-art side-scanning sonar, the team surveyed a seventy-square-mile area south-southeast of Cape Hatteras, locating nearly two dozen shipwrecks. One of them proved to be the long-lost navy ironclad.

When Kane contacted Newton and told him of his correspondence with Horst Degen, the scientist became interested in adding U-701 to his roster of shipwrecks under investigation. After reviewing the US Navy file on U-701 and Degen’s recollection of the U-boat’s position, course, and speed at the time of Kane’s attack, the team, with Kane as an observer, set sail in August 1980 for a three-week survey of the underwater tract that promised to be the boat’s final resting place. Despite their pleas to Degen to join them on the hunt, the former U-boat commander politely declined, citing personal health reasons, but wished them luck in the search. Alas, the U-boat went undetected. U-701 would remain lost for another decade.

11

While Kane was disappointed that the research group hadn’t found the long-lost U-boat, he and his wife, Marguerite, had a very rewarding experience two years later in July 1982 when they visited Horst and Lotte Degen in West Germany. It was the fortieth anniversary of the two war veterans’ dramatic encounter in the North Atlantic, and they were meeting face-to-face for only the second time in the four intervening decades since their brief and violent confrontation off Cape Hatteras. Degen’s first words to his friend confirmed that, for the two of them, battle was no longer the defining event that had brought them together. In the interceding years, Degen had no doubt reflected on the fact that, at the moment of his rescue, he was wearing an American lifejacket with the name “Bellamy” stenciled on the back. It was thrown out of the A-29 Hudson by Corporal George E. Bellamy, Kane’s bombardier. Now, in a departure from his first words to Kane in the Norfolk hospital—“Congratulations, good attack”—Degen grasped Kane’s hand in a firm handshake and said, “Thank you, Harry, for saving my life.”

12

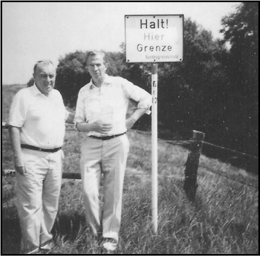

Forty years after their wartime encounter off Cape Hatteras, Harry Kane (left) and Horst Degen (right) met at Degen’s home in Lüneberg, West Germany, in the summer of 1982. COURTESY OF MARGUERITE KANE JAMESON.

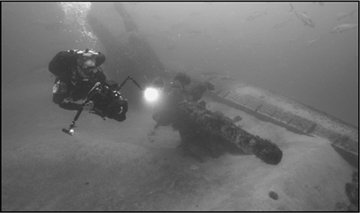

More than seven decades after the Battle of the Atlantic, scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) regularly survey wartime shipwrecks along the North Atlantic coast. Here, NOAA archeologist Russ Green captures imagery of U-701 during a 2011 inspection of the U-boat. COURTESY OF NOAA/PHOTOGRAPHER JOE HOYT.

U-701 still rests on the North Atlantic seabed several dozen miles off Cape Hatteras more than seven decades after its daring patrol off the US East Coast. Half covered by sediment, its interior blocked by accumulated sand, the Type VIIC U-boat lies at a twenty-degree tilt, unmoved by the steady flow of the Gulf Stream current. Buried with the boat are at least a half dozen of its crewmen who never got out after the aerial depth charges ripped open the pressure hull. Not far away are the decaying hulls of two of its victims, the patrol vessel

YP-389

and oil tanker

SS William Rockefeller

, along with at least three other U-boats and scores of Allied merchant ships, as well as scores of Allied sailors and merchant seamen who went down in the fiery conflict that raged nonstop for six months in 1942.

Sport diver Uwe Lowas discovered U-701 in May 1989 after solving the riddle of the U-boat’s location, which had perplexed so many people over the years. Taking Degen’s recollection that moments before the attack, lookout Kurt Hänsel had sighted a partially submerged shipwreck dead ahead on the U-boat’s course of 320 degrees, Lowas delved into the archives for a merchant ship that matched the description of a half-sunk freighter whose superstructure remained visible, with a solitary funnel bracketed by two cargo cranes. Lowas and colleagues Reinhart Lowas and Alan Russell came up with the 6,160-ton British freighter

Empire Thrush

, which was torpedoed by U-203 several hours after sunrise on Tuesday, April 14, 1942, about eight miles north of Diamond Shoals. Taking the reverse bearing from the shipwreck, Lowas used a towed magnetometer and found a large metallic contact on the seabed that turned out to be the hulk of U-701.

News of the discovery, which Lowas and his colleagues kept close to their vests for many months, brought final closure to the two elderly veterans who had shaped the U-boat’s story. Lowas informed Harry Kane of the finding several months before the pilot’s death at the age of seventy-two on September 30, 1990. Two years later, on July 7, 1992, Lowas and four other divers went down to the wreck site of U-701 and released a memorial wreath from Horst Degen commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the sinking. At Degen’s request, they did not affix the wreath to the hull but instead released it over the site to allow it to drift with the Gulf Stream as its surviving crewmen had done for forty-nine hours so long ago. The gesture no doubt brought comfort to Degen in his final years before he too passed at the age of eighty-two on January 29, 1996.

13

*

This was described in detail in the author’s book

Turning the Tide: How a Small Band of Allied Sailors Defeated the U-boats and Won the Battle of the Atlantic

(New York: Basic Books, 2011).

MY FASCINATION WITH THE SAGA of the German U-boat U-701—its daring mine-laying mission, its hunt for Allied shipping off Cape Hatteras, and its destruction by an Army Air Forces A-29 Hudson bomber—goes back a very long way, and my thanks to those who helped me create this account are many.

First and foremost, I want to thank my wife, Karen Conrad, whose loving support sustained me throughout the long months of research and writing.

Once more, the team at Perseus Books Group and its imprint, Basic Books, demonstrated their full commitment to this author’s project. My deepest thanks to Basic publisher and editorial director Lara Heimert and editor Alex Littlefield. I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating: they and the rest of the people at Perseus/Basic Books—particularly, Perseus CEO David Steinberger and Basic managing editor Chris Granville—have created an organization that brings out the best in the writers they work with. I also want to thank copy editor Jennifer Kelland, for her hard work polishing my prose, and illustrator-cartographer Robert E. Pratt, for his excellent charts and illustrations. I also must thank my agent, Deborah Grosvenor, for her unstinting support for this book project.

In the summer of 1974, while I was working as a newspaper reporter in Tidewater, Virginia, I first heard anecdotes about a bizarre combat incident that had taken place at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay just three decades earlier. A German U-boat had managed to elude coastal defenses and lay a minefield across the Thimble Shoal Channel, seriously damaging two ships and destroying two others. Because of wartime censorship, details of the incident remained buried.

In that era long before the Internet and Google, it took a sustained effort to find people decades after an event and thousands of miles away. Thanks to renowned German naval historian Jürgen Rohwer, I was able to locate Horst Degen at his home in Lüneberg, West Germany, and, through him, to find Harry Kane in his hometown of Kinston, North Carolina. Officials at the Naval Historical Center—today part of the Naval History and Heritage Command—were most helpful in providing a copy of the 1942 Office of Naval Intelligence report on the sinking of U-701.

Five years later, George Hebert, my editor at the

Ledger-Star

newspaper in Norfolk, strongly supported my interest in writing a comprehensive account of the incident and provided me with the time and resources to research and write a major three-part series on U-701 that appeared in the

Ledger-Star

in July 1982, the fortieth anniversary of the sinking. Nearly three decades later, that journalism project now forms the foundation of this book.

While I was finishing up my history of the 1943 crisis in the Battle of the Atlantic,

Turning the Tide

, a chance encounter occurred that opened the door for a book about the tale of U-701. Retired US Navy Captain Jerry Mason—whose website, U-boat Archive (

www.uboatarchive.net

), is a rich resource for historical documents concerning the World War II U-boat Force—had been a keen supporter of

Turning the Tide

. When that project was finished, we were chatting on the phone one day, and he asked me if I planned to write another book. I told him that I had written a major series thirty years earlier on a U-boat that had mined the Chesapeake Bay and was thinking that if I could find sufficient information on the incident, a book-length project might be possible.

“What U-boat was involved?” Jerry asked.

“U-701,” I replied.

“Oh—Horst Degen’s boat,” he said.

I was stunned.

“Jerry, the Germans commissioned 1,168 U-boats before and during the war,” I said. “I can’t believe that you have memorized the names of the commanders of every single one!”

Jerry laughed. “No,” he said. “I’m a good friend of his son.”

That was how I was introduced to Dr. Günther Degen, a retired professor of literature in Dusseldorf, Germany, and his English wife, Caroline who became friends and strong collaborators in this project. Günther and Caroline helped organize, and joined Karen and me on, a fascinating and productive research trip across Germany in the fall of 2011. In the town of Suhl, Gerhard Schwendel, the last living survivor of U-701, provided a detailed and gripping account of his wartime experiences on the U-boat, interrupted only by a sumptuous meal prepared by his daughter, Elke Reif. As I was polishing the draft manuscript of this book in late September 2013, I was saddened to learn that Herr Schwendel had passed away two days after celebrating his ninety-first birthday. In the North Sea city of Cuxhaven, the Deutsches U-boot Museum is the largest single repository of information on the German U-boat Force. There, archive founder Horst Bredow—a World War II U-boat veteran who established the archive in 1947 and remains its managing director—provided substantial documentation about the German U-boat Force and U-701. Retired German navy Captain Peter Monte, an associate of Herr Bredow, led a tour of the archive and gave generously of his time translating numerous technical documents into English. At the Baltic seacoast village of Laboe near Kiel, visitors can climb inside U-995, the last surviving Type VIIC U-boat. It has been restored as a museum ship adjoining the Laboe Naval Memorial to the 27,490 German submariners who perished in the war. The staff members of the naval memorial were most helpful.