The Colosseum (4 page)

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

5. The classic image of the Colosseum, immortalised on countless postcards, souvenirs – and as the design on the modern Italian five cent coin.

Nonetheless, those archaeologists who rather loftily suggest that the fame of the Colosseum is a modern invention – a result of our own obsessions and not much to do with the Romans – must be wrong. Or at least they fly in the face of a good deal of evidence for the monument’s ancient renown. The most extravagant example of this is the slim book of verse specially composed by the Roman poet Martial to celebrate the inaugural games in the Colosseum, where no hype is spared in praising the building. The opening poem explicitly ranks it ahead of an international, and partly mythical, roster of ancient Wonders of the World: the pyramids, the city walls of Babylon, the temple of Diana at Ephesus, the altar made by the god Apollo on the island of Delos (from horns of deer that his sister Artemis had killed) and the tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassus. To quote Henry Killigrew’s jaunty seventeenth-century translation:

Egypt

, forbear thy Pyramids to praise,

A barb’rous Work up to a Wonder raise;

Let

Babylon

cease th’incessant Toyl to prize,

Which made her Walls to such immensness rise!

Nor let th’

Ephesians

boast the curious Art,

Which Wonder to their Temple does impart.

Delos

dissemble too the high Renown,

Which did thy Horn-fram’d Altar lately crown;

Caria

to vaunt thy Mausoleum spare,

Sumptuous for Cost, and yet for Art more rare,

As not borne up, but pendulous i’th’Air:

All Works to

Caesar

’s Theatre give place,

This Wonder

Fame

above the rest does grace.

Of course, Martial was not an impartial witness. As the in-house poet of the imperial court, one might argue, it was his job not simply to reflect the fame of the monument but to use his art to

make it famous

. If so, then he was strikingly successful, as a vivid account (by the late-Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus) of the visit of the emperor Constantius II to Rome in

AD

357 suggests. Constantius had been emperor for twenty years but had never actually been to the capital before; most of his reign had been spent dealing with the Persians in the East and with rivals to his throne in other parts of the empire. Combining public business with some energetic sightseeing around the attractions of the city, he is said to have been very struck by the ‘huge bulk of the amphitheatre’. True, there were other monuments also reported to have caught his attention, and pride of place seems to have gone to Trajan’s Forum, where he stood ‘transfixed with astonishment’. But the Colosseum was not far behind, a building so tall that ‘the human eye can hardly reach its highest point’.

It was not just a matter of literary fame, however. Perhaps the clearest indication of the monument’s importance in the Roman world is the rash of imitations it spawned. Although there were several earlier stone amphitheatres, once the Colosseum had been built it seems to have become the model for many, if not most, of those that followed, both in Italy and in the provinces – well over two hundred by the end

of the second century

AD

on current estimates. The façade of the Capua amphitheatre in southern Italy, for example, which seems to have had a succession of columns in the different architectural orders – Tuscan, Ionic and Corinthian – immediately evokes its predecessor in Rome. Further afield, the third-century amphitheatre at El Jem in modern Tunisia (which still dominates its modern town almost as dramatically as does the Colosseum) seems to have been designed so closely on the pattern of the Roman example as to be in effect ‘a shrunken Colosseum’. Exactly how the design was copied or what technical processes of architectural imitation were involved, we do not know. But somehow the Colosseum became an almost instant archetype, a marker of ‘Romanness’ across the empire.

A variety of factors combined to give the Colosseum this iconic status in ancient Rome. As the reaction of Constantius implies, size was certainly important. It was, by a considerable margin, the biggest amphitheatre in the empire; in fact some of the more modest structures, such as those at Chester or Caerleon in Britain, would have fitted comfortably into the space of the Colosseum’s central arena. But size was not everything. The strong association of both the form and function of the building with specifically

Roman

culture also played a part. Many individual elements of the design certainly derived from Greek architectural precedents, but the form as a whole was, unusually, something distinctively Roman – as were the activities that went on within it (even if gladiatorial spectacles were later enthusiastically taken up in the Greek world). A key factor too was the role of the Colosseum in Roman history and politics. For it not only signalled the pleasures of popular entertainment,

it also symbolised a particular style of interaction between the Roman emperor and the people of Rome. It stood at the very heart of the delicate balance between Roman autocracy and popular power, an object lesson in Roman imperial statecraft. This is clear from the very moment of its foundation: its origins are embedded in an exemplary tale of dynastic change, imperial transgression, and competition for control of the city of Rome itself.

‘ROME’S TO IT SELF RESTOR’D’

The history of the Colosseum goes back to the year

AD

68, when after a flamboyant reign the emperor Nero committed suicide. The senate had passed the ancient equivalent of a vote of no confidence, his staff and bodyguards were rapidly deserting him. So the emperor made for the out-of-town villa of one of his remaining servants and (with a little help) stabbed himself in the throat – reputedly uttering his famous boast, ‘What an artist dies in me!’ (‘

Qualis artifex pereo

’), interspersed with appropriately poignant quotes from Homer’s

Iliad

. Eighteen months of civil war followed. The year 69 is often now given the euphemistic title ‘Year of the Four Emperors’, as four aristocrats, each with the support of one of the regional armies (Spain, Danube, Rhine and Syria) competed for succession to the throne – wrecking the centre of Rome in the process and burning down the great temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. But the end result was the victory of a coalition backing Titus Flavius Vespasianus, now usually known simply as ‘Vespasian’.

Vespasian was the general in charge of the Roman army suppressing the Jewish rebellion which had erupted in 66.

After a long siege and huge loss of life, Jerusalem was captured and ransacked under the immediate command of Vespasian’s son, Titus, in 70. Scurrilous Jewish stories, preserved in the Talmud, told how Titus had desecrated the Holy of Holies by having sex with a prostitute on the holy scriptures (a sacrilege avenged by the good God who sent a flea which penetrated Titus’ brain, drummed mercilessly inside his skull and – as was revealed by autopsy – caused a tumour which eventually killed him). Some Roman stories were hardly less fantastic. It was said that while still in the East Vespasian, as newly declared emperor, legitimated his rule by a series of miracles (curing the lame with his foot and the blind with the spittle from his lips). In fact, more prosaically, the emperor and prince spent a leisurely time in the rich eastern provinces raising taxes to repair the damage to state finances caused by Nero’s extravagances. They returned to Rome – first Vespasian, then Titus – to celebrate a joint triumph over the Jews in 71.

This triumphal procession proclaimed the end of civil war, the supreme power of the Roman state and popular hopes for future happiness; or so we are told by a writer who may well have witnessed the ceremony, the historian Josephus, once himself a rebel Jewish commander, now a turncoat favourite at the Roman court. The two generals, dressed in ceremonial purple costume, travelling in a chariot drawn by white horses, made their way through the streets of Rome. In the procession, the conquering soldiers displayed a selection of their prisoners (apparently Titus had specially chosen the handsome ones) and their booty to cheering crowds: a mass of silver, gold, ivory and precious gems. Large wagons, like floats in a modern carnival, were decorated with

huge pictures of the war: a once prosperous countryside devastated, rebels slaughtered, towns destroyed or on fire, prisoners praying for mercy. And from the Temple of Jerusalem itself there came curtains ripped from the sanctuary (and destined to decorate Vespasian’s palace), a scroll containing the Jewish Law, a solid-gold table and the seven-branched candelabra, the Menorah, whose image still clearly stands out on the triumphal arch in honour of Titus at the east end of the Forum (illustration 6). On the ruined Capitoline hill, the procession halted in front of the Temple of Jupiter Best and Greatest. Only after Simon son of Gioras, the defeated Jewish general, had been executed did Vespasian and Titus say prayers and sacrifice; the people cheered and feasted at public expense. Rome’s imperial regime was safely restored.

The new emperor Vespasian’s first task was to reconstruct the ceremonial centre of Rome, to stamp his own identity on the city and to wipe away the memory of Nero. He rebuilt the Temple of Jupiter and constructed a vast new Temple of ‘Peace’, a celebration of Rome’s military success (‘Pacification’ might be a better title) as much as its civilising mission. The obvious problem, however, was what to do with the most notorious of Nero’s building schemes: his vast palace known as the Golden House, whose parkland had taken over a substantial swathe of the city centre, up to 120 hectares (300 acres) in some modern (and probably exaggerated) estimates. The surviving wing of this architectural extravaganza amounts to some 150 rooms preserved in the foundation of the later Baths of Trajan. These were opened again to the public for a few years in the early 2000s, but are now closed once more because of the dangerous condition of the building (in any case, the famous painted decoration is sadly dilapidated and nothing to compare with what Raphael and his friends saw when they rediscovered the site in the sixteenth century). Originally the Golden House’s highlights were said to have included a state-of-the-art dining room with revolving ceiling, a colossal bronze statue, more than likely representing Nero himself, some 30 metres tall, and a private lake – ‘more like a sea than a lake’, according to Nero’s Roman biographer, Suetonius – surrounded by buildings made to represent cities. Much of the ancient report of this palace is overblown. Recent excavation on the site of the lake, for example, has suggested that far from being ‘more like a sea’, with all the images of wild nature that implies, it was a relatively small, rather formal affair. And there is no good reason to suppose, as was alleged soon after, that Nero had himself started the great fire of Rome in 64, simply in order to get his hands on vacant building land (even if he took advantage of the trail of emptiness and devastation the fire had left in bringing his grandiose schemes to fruition). Nonetheless there seems to have been a strong view at the time that the Golden House was monopolising, for the emperor’s private pleasure, space in the centre of the city that by rights belonged to the Roman people. ‘Citizens emigrate to Veii, Rome has become a single house’, as one squib put it at the time.

6. A sculptured panel on Arch of Titus in Rome depicts the parade of booty from the sack of Jerusalem in the triumphal procession of

AD

71. As this seventeenth-century engraving shows more clearly than the now eroded original sculpture, the menorah from the Temple was given pride of place among the spoils.

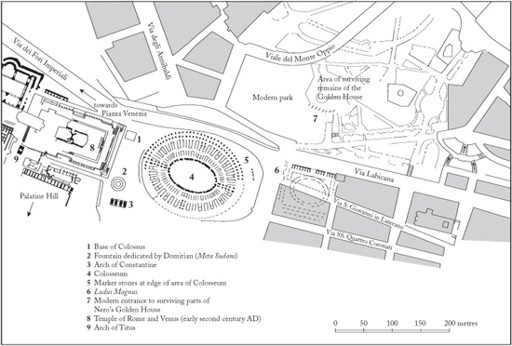

Figure 2. The Colosseum and its surroundings.

Vespasian’s response was shrewd and practical. Part of the Golden House appears to have continued in imperial use (and there is a good case for suggesting that Titus had his residence there a good decade after Nero’s death). But on the site of that infamous private lake he founded what we now call the Colosseum, a pleasure palace for the people. It was a brilliantly calculated political gesture to obliterate Nero’s

memory with a monument to public entertainment, and by giving back to popular use space that had been monopolised by private imperial luxury. And it was a theme harped on by Martial in the second poem of his celebratory volume, which marked the opening of the building almost ten years later, under Titus, in 80 (Vespasian himself did not live to see its final completion, dying in 79). To quote Killigrew’s translation again, which hails the emperor, as Martial’s original did, under the Latin title ‘Caesar’: