The Colosseum (8 page)

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

8. Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting,

Pollice Verso

(‘Thumbs turned’), captures the moment when the audience demand the slaughter of the defeated gladiator.

Its reconstruction not only of the gladiators’ costumes, but also of the decoration surrounding the arena, lies behind many later recreations of the Colosseum, including Ridley Scott’s in

Gladiator

.

This is the painting that is supposed to have inspired the director of

Gladiator

, Ridley Scott: ‘That image spoke to me of the Roman Empire in all its glory and wickedness,’ he is quoted as saying. ‘I knew right then and there I was hooked.’ It also forms a sequel to another painting of Gérôme’s, finished a decade or so earlier in 1859. In this other canvas (which has ended up in Yale University Art Gallery) we see a small posse of gladiators who have just entered the Colosseum’s arena – obviously not the first fighters of the day, to judge from the corpse past which they have just had to walk. They raise their arms to acknowledge the emperor. The title of the painting, again in Latin, is that famous phrase: ‘

Ave Caesar. Morituri te salutant!

’ ‘Hail Caesar. Those about to die salute you!’

9. Asterix and Obelix refuse to utter the famous greeting to Caesar before the gladiatorial games (and are inadvertently more historically accurate than the well-trained posse of fighters in front of them). Not so accurate is the setting. The Colosseum was not yet built at the time the plucky Gauls were outwitting Julius Caesar.

Sadly, there is no evidence at all that this phrase was ever uttered in the Colosseum, still less that it was the regular salute given by gladiators to the emperor. Ancient writers, in fact, quote it in relation to one specific spectacle only, and not a gladiatorial one. According to the biographer Suetonius – and Dio has much the same story – it was the phrase used by the ‘naval fighters’ (‘

naumacharii

’; condemned criminals according to the historian Tacitus) in a spectacular mock battle on the Fucine Lake in the hills east of Rome, put on in

AD

52 by the emperor Claudius, just before his almost equally spectacular feat of draining the lake. The story was that when the emperor heard the word ‘

morituri

’ (‘those who are about to die’) he made a feeble joke by muttering ‘or not, as the case may be’. Somehow the

naumacharii

picked this up and, taking it as a pardon, refused to fight. The emperor was forced to hobble off his throne and persuade the men back to the fight. This frankly implausible tale (how on earth were the fighters on the lake supposed to have heard the words muttered from the safe distance of the imperial throne?) is the only reference we have to the words which have become the slogan of gladiatorial combat in general, and of the Colosseum in particular, in modern culture (illustration 9).

Many of the other elements of the standard reconstruction of arena shows – whether in film, fiction, popular guidebooks or specialist accounts – are only slightly less tenuous. It is certainly the case, for example, that we have plenty of evidence for different types of gladiator, indicated by an array of carefully distinguished titles. Tombstones of fighters often specify

this precisely. A wonderfully elaborate memorial from Rome commemorates a ‘Thracian’ from Alexandria, who came to Rome to take part in the shows in honour of the emperor Trajan’s victories in

AD

117; he did not live to go home (illustration 10). Another commemorates a gladiator who came from Florence, who died after thirteen fights at the age of twenty-two leaving a wife and two children (and blunt advice to anyone reading his tombstone ‘to kill whoever you defeat’); he is said to have been a ‘

secutor

’ (‘Pursuer’). Meanwhile in poignant graffiti scratched on a wall at Herculaneum, a town that was to be buried under volcanic debris just as the building of the Colosseum in Rome was reaching completion, a gladiator vows his shield to the goddess Venus if he wins: his name is Mansuetus (a presumably ironic stage-name meaning ‘Gentle’); he describes himself as a ‘

provocator

’ (‘Challenger’). It is clear enough too that these different types attracted their own groups of fans. The emperor Titus was, according to Suetonius, a self-confessed supporter of the Thracians and enjoyed arguing their merit with the crowd, just like any fan – ‘though without losing his dignity or sense of justice’, Suetonius assures us. Not so his younger brother Domitian, who was a follower of the

murmillones

. On one occasion, a man in the audience was heard to hint that it was impossible for a Thracian to win while the emperor was using his influence to secure a victory for the ‘fish-heads’. In one of those mini dramas that must (in the telling, at least) have increased the excitement of the show, Domitian had him yanked out of the crowd and thrown to the dogs in the arena with an explanatory placard around his neck:

parmularius impie

. No translation can match the Latin’s brevity: ‘a Thracian fan, but sacrilegious’.

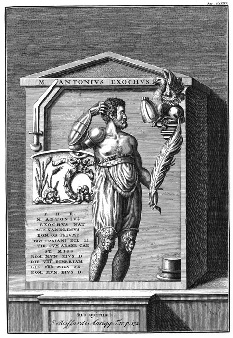

10. This illustration from an early collection of Roman inscriptions captures a rather different image of a gladiator – much influenced, in this rendering, by seventeenth-century style. The tombstone (now lost and no doubt considerably restored in this picture) commemorates one Marcus Antonius Exochus who, as the text explains, took part in gladiatorial games to celebrate the triumph of the emperor Trajan in the early second century

AD

.

The trouble comes when we try to match up these different titles with the visual images of gladiators and gladiatorial fights in sculpture, graffiti, paintings and mosaics from places as far afield as Germany and Libya. For in the absence of any surviving ancient accounts which explain the typology, this is the only way that historians have hoped to work out the details of the different styles of costume and different fighting methods adopted by the various brands of combatant. Some distinct categories do emerge. There are clearly contrasting types of helmet. One, for example, seems entirely to cover the face apart from two tiny eye-holes. This is generally thought to belong to the

secutor

(title page). Others have a broad brim, and were probably worn by Thracians and

murmillones

(illustration 8,

p. 57

) – though the general absence of fish emblems makes some historians think that it was the overall ‘fishy’ shape that gave the

murmillo

his title. But most of the evidence resists easy categorisation. So, for example, despite their name, ‘Net-men’ are commonly shown with their tridents, but only very rarely shown carrying nets. Is this because ancient artists found nets a tricky subject to represent? Or because, however these fighters originated, by the first century

AD

(

pace

Gérôme) they no longer in practice used this particular piece of equipment very often? For other categories, it proves very difficult to see exactly what the difference between them might consist in. Was the Thracian the same as a ‘

hoplomachus

’ (‘shield-fighter’)? Or was there, as some archaeologists try to argue, a crucial variation in the shape of his shield? Were ‘Samnites’ just an earlier form of the

murmillones

? And what of those categories that are mentioned in literature or on tombstones, but never seem to be represented in images? Why can we find no images of the

‘

essedarii

’ (‘chariot-fighters’), so often referred to in written sources?

A telling case is one of the most startling and now most frequently reproduced images of any fighter in the arena: a unique bronze

tintinnabulum

(bell chimes) from Herculaneum, cast in the form of a gladiator attacking his own elongated penis which is half-transformed into a panther or wolf. Leaving aside the difficult questions of where this nightmarish creature might have been displayed, by whom and why – it is a favourite object among modern historians, who want to illustrate the complex identity of the gladiator, and especially the dangerous ambivalence of his sexuality, a subject we shall return to in

Chapter 4

. In killing the animal, this fighter will castrate himself. ‘There is no more apt icon for the Roman cosmology of desire, and the place of the gladiator within it,’ as one writer has recently put it. But is he a gladiator at all, in the strict sense of the word? His headdress certainly bears little resemblance to that in other images of gladiators. Maybe we should better see him as one of the beast hunters in the arena, a much less common subject of ancient art or literature. Or maybe – and this would fit with his strangely dwarfish physique – he is meant to be a theatrical or mime artist. For all his fame in modern accounts of gladiatorial combat, he is a classic illustration of just how hard it is to pin images of gladiators down.

The fact is that modern accounts which list and illustrate the different gladiatorial types plus their characteristic weapons, and define their particular roles in the arena (‘the usual tactics of the

secutor

were to try closing in on his adversary’s body with his shield held in front of him’, and such like), are at best over-zealous attempts to impose order on the wide diversity of evidence that survives. Different types of gladiators with different names there certainly were – but how exactly each one was equipped, what particular role they took in the fighting and how that differed over the centuries of gladiatorial display throughout the whole expanse of the Roman empire is very hard indeed to judge.

11. The Freudian fighter? This set of chimes presents an unnerving image of self-castration. But is the figure, as many modern writers assume, really meant to be a gladiator?

The question becomes even more tantalizing when we try to fit into the picture the authentic items of gladiatorial armour that still survive – splendid helmets, shields, protections for shoulders and legs (or perhaps arms: to be honest, it is not always clear exactly which part of the body the makers had in mind). There is a considerable quantity of this, most of it, about 80 per cent, from the gladiatorial barracks at Pompeii, excavated in the eighteenth century. At first sight, even if it is not from the Colosseum itself, this material provides precious direct evidence of what an ancient combatant in that arena would have worn, only a few years before the monument’s inauguration. And it matches up reasonably well with some of the surviving ancient images of gladiators. Yet it is far too good to be true … quite literally. Most of the helmets are lavishly decorated, embossed with figures of barbarians paying homage to the goddess ‘Roma’ (the personification of the city), of the mythical strongman Hercules and with a variety of other more or obviously appropriate scenes. It perhaps fits well with Martial’s emphasis on the arena’s sophisticated play with stories from classical mythology that one of these helmets (illustration 12) is decorated with figures of the Muses. It is also extremely heavy. The average weight of the helmets is about 4 kilos, which is about twice that of a standard Roman soldier’s helmet; the heaviest weighs in at almost 7 kilos. Add to this the fact that none of them seem to show any sign of wear and tear – no nasty bash where a sword or a trident came down fiercely, no dent where the shield rolled off and hit the ground. It is hard to resist the suspicion that these magnificent objects were not actually gladiatorial equipment in regular use.