The Coming of the Third Reich (13 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

III

Like other European nations, Germany went into the First World War in an optimistic mood, fully expecting to win, most probably in a relatively short space of time. Military men like the War Minister, Erich von Falkenhayn, expected a longer conflict and even feared that Germany might eventually be defeated. But their expert view did not communicate itself to the masses or, indeed, to many of the politicians in whose hands Germany’s destiny lay.

108

The mood of invincibility was buoyed up by the massive growth of the German economy over the previous decades, and fired on by the stunning victories of the German army in 1914-15 on the Eastern Front. An early Russian invasion of East Prussia led the Chief of the German General Staff to appoint a retired general, Paul von Hindenburg, born in 1847 and a veteran of the war of 1870-71, to take over the campaign with the aid of his Chief of Staff, Erich Ludendorff, a technical expert and military engineer of non-noble origins who had won a reputation for himself with the attack on Liege at the beginning of the war. The two generals enticed the invading Russian armies into a trap and annihilated them, following this with a string of further victories. By the end of September 1915 the Germans had conquered Poland, inflicted huge losses on the Russian armies and driven them back over 250 miles from the positions they had occupied the previous year.

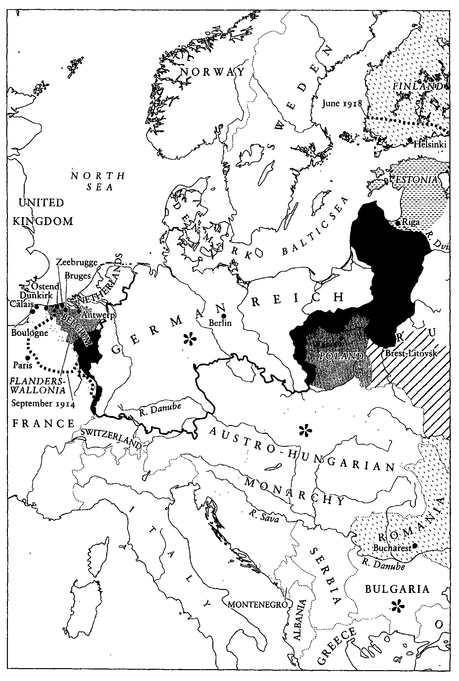

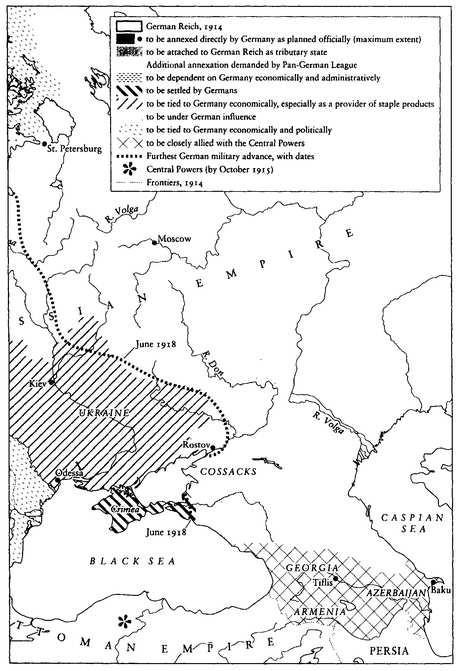

Map 2.

German Expansion in the First World War

These achievements made the reputation of Hindenburg as a virtually invincible general. A cult of the hero quickly developed around him, and his massive, stolid presence seemed to provide an element of stability amid the changing fortunes of war. But he was in fact a man of limited political vision and ability. He acted in many ways as a front for his energetic subordinate Ludendorff, whose ideas about the conduct of the war were far more radical and ruthless than his own. The pair’s triumphs in the East contrasted sharply with the stalemate in the West, where within a few months of the outbreak of war, some eight million troops were facing each other along 450 miles of trenches from the North Sea to the Swiss border, unable to penetrate to a meaningful degree into the enemy lines. The soft ground allowed them to construct line after line of deep defensive trenches. Barbed-wire entanglements impeded the enemy’s advance. And machine-gun emplacements all along the line mowed down any troops from the other side that succeeded in getting close enough to be shot at. Both sides threw increasing resources into this futile struggle. By 1916 the strain was beginning to tell.

In all the major combatant nations, there was a change of leadership in the middle years of the war, reflecting a perceived need for greater energy and ruthlessness in mobilizing the nation and its resources. In France, Clemenceau came to power, in Britain Lloyd George. In Germany, characteristically, it was not a radical civilian politician, but the two most successful generals, Hindenburg and Ludendorff, who took over the reins of power in 1916. The ‘Hindenburg Programme’ attempted to galvanize and reorganize the German economy to bend it to the overriding purpose of winning the war. Run by another middle-class general, Wilhelm Groener, the War Office co-opted the trade unions and civilian politicians in the task of mobilization. But this was anathema to the industrialists and the other generals. Groener was soon dispensed with. Pushing the civilian politicians aside, Hindenburg and Ludendorff established a ‘silent dictatorship’ in Germany, with military rule behind the scenes, severe curbs on civil liberties, central control of the economy and the generals calling the shots in the formulation of war aims and foreign policy. All of these developments were to provide significant precedents for the more drastic fate that overtook German democracy and civil freedom less than two decades later.

109

The turn to a more ruthless prosecution of the war was counter-productive in more than one sense. Ludendorff ordered a systematic economic exploitation of the areas of France, Belgium and East-Central Europe occupied by German troops. The occupied countries’ memory of this was to cost the Germans dearly at the end of the war. The generals’ inflexible and ambitious war aims alienated many Germans in the liberal centre and on the left. And the decision at the beginning of 1917 to undertake unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic in order to cut off British supplies from the United States only provoked the Americans to enter the war on the Allied side. From 1917, the mobilization of the world’s richest economy began to weigh heavily on the Allied side, and by the end of the year American troops were coming onto the Western Front in ever increasing numbers. The only really bright spot from the German point of view was the continuing string of military successes in the East.

But these, too, had a price. The relentless military pressure of the German armies and their allies in the East bore fruit early in 1917 in the collapse of the inefficient and unpopular administration of the Russian Tsar Nicholas II and its replacement with a Provisional Government in the hands of Russian liberals. These proved no more capable than the Tsar, however, of mobilizing Russia’s huge resources for a successful war. With near-famine conditions at home, chaos in the administration and growing defeat and despair at the front, the mood in Moscow and St Petersburg turned increasingly against the war, and the already precarious legitimacy of the Provisional Government began to disappear into thin air. The chief beneficiary of this situation was the only political grouping in Russia that had offered consistent opposition to the war from the very beginning: the Bolshevik Party, an extremist, tightly organized, ruthlessly single-minded Marxist group whose leader, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, had argued all along that defeat in war was the quickest way to bring about a revolution. Seizing his chance, he organized a swift coup in the autumn of 1917 that met with little immediate resistance.

The ‘October Revolution’ soon degenerated into bloody chaos. When opponents of the Bolsheviks attempted a counter-coup, the new regime responded with a violent ‘red terror’. All other parties were suppressed. A centralized dictatorship under Lenin’s leadership was established. A newly formed Red Army led by Leon Trotsky fought a bitter Civil War against the ‘Whites’, who aimed to re-establish the Tsarist regime. Their efforts could not help the Tsar himself, whom the Bolsheviks quickly put to death, along with his family. The Bolsheviks’ political police organization, the Cheka, ruthlessly suppressed the regime’s opponents from every part of the political spectrum, from the moderate socialist Mensheviks, the anarchists and the peasant Social Revolutionaries on the left to liberals, conservatives and Tsarists on the right. Thousands were tortured, killed or brutally imprisoned in the first camps in what was to become a vast system of confinement by the 1930s.

110

Lenin’s regime eventually triumphed, seeing off the ‘Whites’ and their supporters, and establishing its control over much of the former Tsarist Empire. The Bolshevik leader and his successors moved to construct their version of a communist state and society, with the socialization of the economy representing, in theory at least, common ownership of property, the abolition of religion guaranteeing a secular, socialist consciousness, the confiscation of private wealth creating a classless society, and the establishment of ‘democratic centralism’ and a planned economy giving unprecedented, dictatorial powers to the central administration in Moscow. All this, however, was happening in a state and society that Lenin knew to be economically backward and lacking in modern resources. More advanced economies, like that of Germany, had in his view more developed social systems, in which revolution was even more likely to break out than had been the case in Russia. Indeed, Lenin believed that the Russian Revolution could scarcely survive unless successful revolutions of the same type took place elsewhere as well.

111

So the Bolsheviks formed a Communist International (‘Comintern’) to propagate their version of revolution in the rest of the world. In doing so they could take advantage of the fact that socialist movements in many countries had split over the issues raised by the war. In Germany in particular, the once-monolithic Social Democratic Party, which began by supporting the war as a mainly defensive operation against the threat from the East, had been beset by increasing doubts as the scale of the annexations demanded by the government began to become clear. In 1916 the party split into pro-war and anti-war factions. The majority continued, with reservations, to support the war and to propagate moderate reforms rather than wholesale revolution. Amongst the minority of ‘Independent Social Democrats’, a few, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, founded the German Communist Party in December 1918. They were eventually joined by the mass of the minority’s supporters in the early 1920s.

112

It would be difficult to exaggerate the fear and terror that these events spread amongst many parts of the population in Western and Central Europe. The middle and upper classes were alarmed by the radical rhetoric of the Communists and saw their counterparts in Russia lose their property and disappear into the torture chambers and prison camps of the Cheka. Social Democrats were terrified that if the Communists came to power in their own country they would meet the fate suffered by the moderate socialist Mensheviks and the peasant-oriented Social Revolutionaries in Moscow and St Petersburg. Democrats everywhere were conscious from the outset that Communism was intent on suppressing human rights, dismantling representative institutions and abolishing civil freedoms. Terror led them to believe that Communism in their own countries should be stopped at any cost, even by violent means and through the abrogation of the very civil liberties they were pledged to defend. In the eyes of the right, Communism and Social Democracy amounted to two sides of the same coin, and the one seemed no less a threat than the other. In Hungary, a short-lived Communist regime under Béla Kun took power in 1918, tried to abolish the Church, and was swiftly overthrown by the monarchists led by Admiral Miklós Horthy. The counter-revolutionary regime proceeded to institute a ‘White terror’ in which thousands of Bolsheviks and socialists were arrested, brutally maltreated, imprisoned and killed. Events in Hungary gave Central Europeans for the first time a taste of the new levels of political violence and conflict that were to emerge from the tensions created by the war.

113

In Germany itself, the threat of Communism still seemed relatively remote at the beginning of 1918. Lenin and the Bolsheviks quickly negotiated a much-needed peace settlement to give themselves the breathing-space they required to consolidate their newly won power. The Germans drove a hard bargain, annexing huge swathes of territory from the Russians at the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk early in 1918. As large numbers of German troops were transferred from the now-redundant Eastern Front to reinforce a new spring offensive in the West, final victory seemed just around the corner. In his annual proclamation to the German people in August 1918, the Kaiser assured everybody that the worst of the war was over. This was true enough, but not in the sense he intended.

114

For the huge blood-letting that Ludendorff’s spring offensive had caused in the German army opened the way for the Allies, reinforced by massive numbers of fresh American troops and supplies, to breach German lines and advance rapidly along the Western Front. Morale in the German army started to collapse, and ever-larger numbers of troops began to desert or surrender to the Allies. The final blows came as Germany’s ally Bulgaria sued for peace and the Habsburg armies in the South began to melt away in the face of renewed Italian attacks.

115

Hindenburg and Ludendorff were obliged to inform the Kaiser at the end of September that defeat was inevitable. A massive tightening of censorship ensured that newspapers continued to hold out the prospect of final victory for some time afterwards when in reality it had long since disappeared. The shock waves sent out by the news of Germany’s defeat were therefore all the greater.

116

They were to prove too strong for what remained of the political system of the empire that Bismarck had created in 1871.