The Coming of the Third Reich (14 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

It was in this cauldron of war and revolution that Nazism was forged. A mere fifteen years separated the defeat of Germany in 1918 from the advent of the Third Reich in 1933. Yet there were to be many twists and turns along the way. The triumph of Hitler was by no means inevitable in 1918, any more than it had been pre-programmed by the previous course of German history. The creation of the German Reich and its rise to economic might and Great Power status had created expectations in many people, expectations that, it was clear by this time, the Reich and its institutions were unable to fulfil. The example of Bismarck as a supposedly ruthless, tough leader who was not afraid to use violence and deception to gain his ends, was present in the minds of many, and the determination with which he had acted to curb the democratizing threat of political Catholicism and the socialist labour movement was widely admired in the Protestant middle classes. The ‘silent dictatorship’ of Hindenburg and Ludendorff had put the precepts of ruthless, authoritarian rule into practice at a moment of supreme national crisis in 1916 and created an ominous precedent for the future.

The legacy of the German past was a burdensome one in many respects. But it did not make the rise and triumph of Nazism inevitable. The shadows cast by Bismarck might eventually have been dispelled. By the time the First World War came to an end, however, they had deepened almost immeasurably. The problems bequeathed to the German political system by Bismarck and his successors were made infinitely worse by the effects of the war; and to these problems were added others that boded even more trouble for the future. Without the war, Nazism would not have emerged as a serious political force, nor would so many Germans have sought so desperately for an authoritarian alternative to the civilian politics that seemed so signally to have failed Germany in its hour of need. So high were the stakes for which everybody was playing in 1914-18, that both right and left were prepared to take measures of an extremism only dreamed of by figures on the margins of politics before the war. Massive recriminations about where the responsibility for Germany’s defeat should lie only deepened political conflict. Sacrifice, privation, death, on a huge scale, left Germans of all political hues bitterly searching for the reason why. The almost unimaginable financial expense of the war created a vast economic burden on the world economy which it was unable to shake off for another thirty years, and it fell most heavily upon Germany. The orgies of national hatred in which all combatant nations had indulged during the war left a terrible legacy of bitterness for the future. Yet as the German armies drifted home, and the Kaiser’s regime prepared reluctantly to hand over to a democratic successor, there still seemed everything to play for.

DESCENT INTO CHAOS

I

In November 1918 most Germans expected that, since the war was being brought to an end before the Allies had set foot on German soil, the terms on which the peace would be based would be relatively equitable. During the previous four years, debate had raged over the extent of territory Germany should seek to annex after the achievement of victory. Even the official war aims of the government had included the assignment to the Reich of a substantial amount of territory in Western and Eastern Europe, and the establishment of complete German hegemony over the Continent. Pressure-groups on the right went much further.

117

Given the extent of what Germans had expected to gain in the event of victory, it might have been expected that they would have realized what they stood to lose in the event of defeat. But no one was prepared for the peace terms to which Germany was forced to agree in the Armistice of 11 November 1918. All German troops were forced to withdraw east of the Rhine, the German fleet was to be surrendered to the Allies, vast amounts of military equipment had to be handed over, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had to be repudiated and the German High Seas Fleet had to be surrendered to the Allies along with all the German submarines. In the meantime, to ensure compliance, the Allies maintained their economic blockade of Germany, worsening an already dire food-supply situation. They did not abandon it until July the following year.

118

These provisions were almost universally felt in Germany as an unjustified national humiliation. Resentment was hugely increased by the actions taken, above all by the French, to enforce them. The harshness of the Armistice terms was thrown into sharp relief by the fact that many Germans refused to believe that their armed forces had actually been defeated. Very quickly, aided and abetted by senior army officers themselves, a fateful myth gained currency among large sections of public opinion in the centre and on the right of the political spectrum. Picking up their cue from Richard Wagner’s music-drama

The Twilight of the Gods,

many people began to believe that the army had only been defeated because, like Wagner’s fearless hero Siegfried, it had been stabbed in the back by its enemies at home. Germany’s military leaders Hindenburg and Ludendorff claimed shortly after the war that the army had been the victim of a ‘secret, planned, demagogic campaign’ which had doomed all its heroic efforts to failure in the end. ‘An English general said correctly: the German army was stabbed in the back.‘

119

Kaiser Wilhelm II repeated the phrase in his memoirs, written in the 1920s: ’For thirty years the army was my pride. For it I lived, upon it I laboured, and now, after four and a half brilliant years of war with unprecedented victories, it was forced to collapse by the stab-in-the-back from the dagger of the revolutionist, at the very moment when peace was within reach!‘

120

Even the Social Democrats contributed to this comforting legend. As the returning troops streamed into Berlin on 10 December 1918, the party leader Friedrich Ebert told them: ‘No enemy has overcome you!’

121

Defeat in war brought about an immediate collapse of the political system created by Bismarck nearly half a century before. After the Russian Revolution of February 1917 had hastened Tsarist despotism to its end, Woodrow Wilson and the Western Allies had begun to proclaim that the war’s principal aim was to make the world safe for democracy. Once Ludendorff and the Reich leadership concluded that the war was irremediably lost, they therefore advocated a democratization of the Imperial German political system in order to improve the likelihood of reasonable, even favourable peace terms being agreed by the Allies. As a far from incidental by-product, Ludendorff also reckoned that if the terms were not so acceptable to the German people, the burden of agreeing to them would thereby be placed on Germany’s democratic politicians rather than on the Kaiser or the army leadership. A new government was formed under the liberal Prince Max of Baden, but it proved unable to control the navy, whose officers attempted to put to sea in a bid to salvage their honour by going down fighting in a last hopeless battle against the British fleet. Not surprisingly, the sailors mutinied; within a few days the uprisings had spread to the civilian population, and the Kaiser and all the princes, from the King of Bavaria to the grand Duke of Baden, were forced to abdicate. The army simply melted away as the Armistice of 11 November was concluded, and the democratic parties were left, as Ludendorff had intended, to negotiate, if negotiate was the word, the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

122

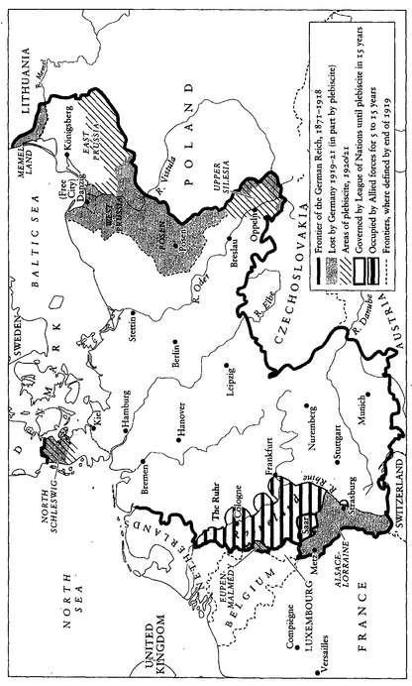

As a result of the Treaty, Germany lost a tenth of its population and 13 per cent of its territory, including Alsace-Lorraine, ceded back to France after nearly half a century under German rule, along with the border territories of Eupen, Malmédy and Moresnet. The Saarland was lopped off from Germany under a mandate with the promise that its people would eventually be able to decide whether they wanted to become part of France; it was clearly expected that in the end they would, at least if the French had anything to do with it. In order to ensure that German armed forces did not enter the Rhineland, British, French and, more briefly, American troops were stationed there in considerable numbers for much of the 1920s. Northern Schleswig went to Denmark, and, in 1920, Memel to Lithuania. The creation of a new Polish state, reversing the partitions of the eighteenth century in which Poland had been gobbled up by Austria, Prussia and Russia, meant the loss to Germany of Posen, much of West Prussia, and Upper Silesia. Danzig became a ‘Free City’ under the nominal control of the newly founded League of Nations, the forerunner of the United Nations organization established after the Second World War. In order to give the new Poland access to the sea, the peace settlement carved out a ‘corridor’ of land separating East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Germany’s overseas colonies were seized and redistributed under mandates from the League of Nations.

123

Just as significant, and just as much of a shock, was the refusal of the victorious powers to allow the union of Germany and German-speaking Austria, which would have meant the fulfilment of the radical dreams of 1848. As the constituent nations of the Habsburg Empire broke away at the very end of the war to form the nation-states of Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, or to join new or old neighbouring nation-states such as Poland and Romania, the six million or so German-speakers left in Austria proper, sandwiched along and beside the Alps between Germany and Italy, overwhelmingly considered that the best course of action was to join the German Reich. Almost nobody considered rump Austria to be either politically or economically viable. For decades the vast majority of its population had thought of themselves as the leading ethnic group in the multi-national Habsburg monarchy, and those who, like Schönerer, had advocated the solution of 1848 - splitting away from the rest and joining the German Reich - had been confined to the lunatic fringe. Now, however, Austria was suddenly cut off from the hinterlands, above all in Hungary, on which it had formerly been so dependent economically. It was saddled with a capital city, Vienna, whose population, swollen by suddenly redundant Habsburg bureaucrats and military administrators, constituted over a third of the total living in the new state. What had previously been political eccentricity now seemed to make political sense. Even the Austrian socialists thought that joining the more advanced German Reich would bring socialism nearer to fulfilment than trying to go it alone.

124

Moreover, the American President Woodrow Wilson had declared, in his celebrated ‘Fourteen Points’ which he wished the Allied powers to be working for, that every nation should be able to determine its own future, free from interference by others.

125

If this applied to the Poles, the Czechs and the Yugoslavs, then surely it should apply to the Germans as well? But it did not. What, the Allies asked themselves, had they been fighting for, if the German Reich ended the war bigger by six million people and a considerable amount of additional territory, including one of Europe’s greatest cities? So the union was vetoed. Of all the territorial provisions of the Treaty, this seemed the most unjust. Proponents and critics of the Allied position could argue over the merits of the other provisions and dispute the fairness or otherwise of the plebiscites that decided the territorial issue in places like Upper Silesia; but on the Austrian issue there was no room for argument at all. The Austrians wanted union; the Germans were prepared to accept union; the principle of national self-determination demanded union. The fact that the Allies forbade union remained a constant source of bitterness in Germany and condemned the new ‘Republic of German-Austria’, as it was known, to two decades of conflict-ridden, crisis-racked existence in which few of its citizens ever came to believe in its legitimacy.

126

Map 3. The Treaty of Versailles

Many Germans realized that the Allies justified their ban on a German-Austrian union, as so much else in the Treaty of Versailles, by Article 231, which obliged Germany to accept the ‘sole guilt’ for the outbreak of the war in 1914. Other articles, equally offensive to Germans, ordained the trial of the Kaiser and many others for war crimes. Significant atrocities had indeed been committed by German troops during the invasions of Belgium and northern France in 1914. But the few trials that did take place, in Leipzig, before a German court, almost uniformly failed because the German judiciary did not accept the legitimacy of most of the charges. Out of 900 alleged war criminals initially singled out for trial, only seven were eventually found guilty, while ten were acquitted and the rest never underwent a full trial. The idea took root in Germany that the whole concept of war crimes, indeed the whole notion of laws of war, was a polemical invention of the victorious Allies based on mendacious propaganda about imaginary atrocities. This left a fateful legacy for the attitudes and conduct of German armed forces during the Second World War.

127