The Coming of the Third Reich (18 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

As it was, changes of government in the Weimar Republic were very frequent. Between 13 February 1919 and 30 January 1933 there were no fewer than twenty different cabinets, each lasting on average 239 days, or somewhat less than eight months. Coalition government, it was sometimes said, made for unstable government, as the different parties were constantly squabbling over personalities and policies. It also made for weak government, since all they could settle on was the lowest common denominator and the line of least resistance. However, coalition government in Weimar was not just the product of proportional representation. It also arose out of long-standing and deep fissures within the German political system. The parties that had dominated the Imperial scene all survived into the Weimar Republic. The Nationalists were formed by the amalgamation of the old Conservative Party with other, smaller groups. The liberals failed to overcome their differences and remained divided into left (Democrats) and right (People’s Party). The Centre Party remained more or less unchanged, though its Bavarian wing split off to form the Bavarian People’s Party. On the left, the Social Democrats had to face a new rival in the form of the Communist Party. But none of this was solely or even principally the product of proportional representation. The political milieux out of which these various parties emerged had been in existence since the early days of the Bismarckian Empire.

13

These milieux, with their party newspapers, clubs and societies, were unusually rigid and homogeneous. Already before 1914 this had resulted in a politicization of whole areas of life that in other societies were much freer from ideological identifications. Thus, if an ordinary German wanted to join a male voice choir, for instance, he had to choose in some areas between a Catholic and a Protestant choir, in others between a socialist and a nationalist choir; the same went for gymnastics clubs, cycling clubs, football clubs and the rest. A member of the Social Democratic Party before the war could have virtually his entire life encompassed by the party and its organizations: he could read a Social Democratic newspaper, go to a Social Democratic pub or bar, belong to a Social Democratic trade union, borrow books from the Social Democratic library, go to Social Democratic festivals and plays, marry a woman who belonged to the Social Democratic women’s organization, enrol his children in the Social Democratic youth movement and be buried with the aid of a Social Democratic burial fund.

14

Similar things could be said of the Centre Party (which could rely on the mass organization of supporters in the People’s Association for a Catholic Germany, the Catholic Trade Union movement, and Catholic leisure clubs and societies of all kinds) but also to a certain extent of other parties too.

15

These sharply defined political-cultural milieux did not disappear with the advent of the Weimar Republic.

16

But the emergence of commercialized mass leisure, the ‘boulevard press’, based on sensation and scandal, the cinema, cheap novels, dance-halls and leisure activities of all kinds began in the 1920s to provide alternative sources of identification for the young, who were thus less tightly bound to political parties than their elders were.

17

The older generation of political activists were too closely tied to their particular political ideology to find compromise and co-operation with other politicians and their parties very easy. In contrast to the situation after 1945, there was no merger of major political parties into larger and more effective units.

18

As in a number of other respects, therefore, the political instability of the 1920S and early 1930S owed more to structural continuities with the politics of the Bismarckian and Wilhelmine eras than to the novel provisions of the Weimar constitution.

19

Proportional representation did not, as some have claimed, encourage political anarchy and thereby facilitate the rise of the extreme right. An electoral system based on a first-past-the-post system, where the candidate who won the most votes in each constituency automatically won the seat, might well have given the Nazi Party even more seats than it eventually obtained in the last elections of the Weimar Republic, though since the parties’ electoral tactics would have been different under such a system, and its arguably beneficial effects in the earlier phases of the Republic’s existence might have reduced the overall Nazi vote later on, it is impossible to tell for sure.

20

Similarly, the destabilizing effect of the constitution’s provision for referendums or plebiscites has often been exaggerated; other political systems have existed perfectly happily with such a provision, and in any case the actual number of plebiscites that actually took place was very small. The campaigning they involved certainly helped keep the overheated political atmosphere of the Republic at boiling point. But national plebiscites had little direct political effect, despite the fact that one provincial plebiscite did succeed in overthrowing a democratic government in Oldenburg in 1932.

21

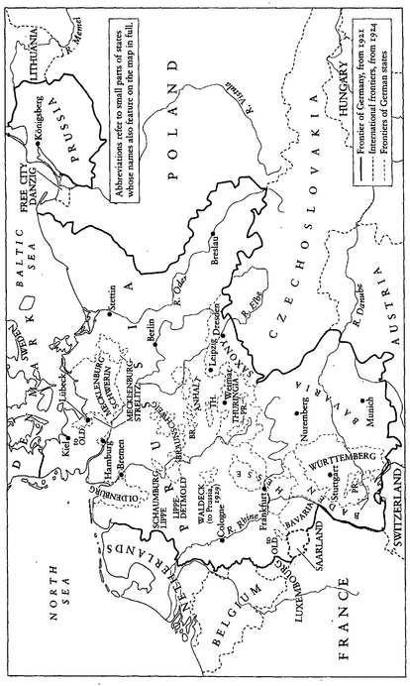

Map 4. The Weimar Republic

In any case, the governmental instability of Weimar has itself often been overdrawn, for the frequent changes of government concealed long-term continuities in particular ministries. Some posts, notably the Ministry of Justice, were used as bargaining counters in inter-party coalition negotiations and so saw a succession of many different ministers, no doubt putting more power than usual into the hands of the senior civil servants, who stayed there all through, though their freedom of action was curtailed by the devolution of many functions of judicial administration to the federated states. But others became the virtual perquisite of a particular politician through all the vagaries of coalition-building, thus making it easier to formulate and implement strong and decisive policies. Gustav Stresemann, the leading figure in the People’s Party, for instance, was Foreign Minister in nine successive administrations and remained in office for an unbroken period of over six years. Heinrich Brauns, a Centre Party deputy, was Minister of Labour in twelve successive cabinets, from June 1920 up to June 1928. Otto Gessler, a Democrat, was Army Minister in thirteen successive governments, from March 1920 to January 1928. Such ministers were able to develop and implement long-term policies irrespective of the frequent turnover of leadership experienced by the governments they served in. Other ministries were also occupied by the same politicians through two, three or four different governments.

22

Not by chance, it was in such areas that the Republic was able to develop its strongest and most consistent policies, above all in the fields of foreign affairs, labour and welfare.

The ability of the Reich government to act firmly and decisively, however, was always compromised by another provision of the constitution, namely its decision to continue the federal structure which Bismarck had imposed on the Reich in 1871 in an effort to sugar the pill of unification for German princes such as the King of Bavaria and the Grand Duke of Baden. The princes had been unceremoniously thrown out in the Revolution of 1918, but their states remained. They were equipped now with democratic, parliamentary institutions, but still retained a good deal of autonomy in key areas of domestic policy. The fact that some of the states, like Bavaria, had a history and an identity going back many centuries, encouraged them to obstruct the policies of the Reich government if they did not like them. On the other hand, direct taxation was now in the hands of the Reich government, and many of the smaller states were dependent on handouts from Berlin when they got into financial difficulties. Attempts at secession from the Reich might seem threatening, especially in the Republic’s troubled early years, but in reality they were never strong enough to be taken seriously.

23

Worse problems could be caused by tensions between Prussia and the Reich, since the Prussian state was bigger than all the rest combined; but through the 1920s and early 1930s Prussia was led by moderate, pro-republican governments which constituted an important counterweight to the extremism and instability of states such as Bavaria. When all these factors are taken into account, therefore, it does not seem that the federal system, for all its unresolved tensions between the Reich and the states, was a major factor in undermining the stability and legitimacy of the Weimar Republic.

24

III

All in all, Weimar Germany’s constitution was no worse than the constitutions of most other countries in the 1920s, and a good deal more democratic than many. Its more problematical provisions might not have mattered so much had circumstances been different. But the fatal lack of legitimacy from which the Republic suffered magnified the constitution’s faults many times over. Three political parties were identified with the new political system - the Social Democrats, the liberal German Democratic Party, and the Centre Party. After gaining a clear majority of 76.2 per cent of the vote in January 1919, these three parties combined won just 48 per cent of the vote in June 1920, 43 per cent of the vote in May 1924, 49.6 per cent in December 1924, 49.9 per cent in 1928 and 43 per cent in September 1930. From 1920 onwards they were thus in a permanent minority in the Reichstag, outnumbered by deputies whose allegiance lay with the Republic’s enemies to the right and to the left. And the support of these parties of the ‘Weimar coalition’ for the Republic was, at best, often more rhetorical than practical, and, at worst, equivocal, compromised or of no political use at all.

25

The Social Democrats were considered by many to be the party that had created the Republic, and often said so themselves. Yet they were never very happy as a party of government, took part in only eight out of the twenty Weimar cabinets and only filled the office of Reich Chancellor in four of them.

26

They remained locked in the Marxist ideological mould of the prewar years, still expecting capitalism to be overthrown and the bourgeoisie to be replaced as the ruling class by the proletariat. Whatever else it was, Germany in the 1920s was undeniably a capitalist society, and playing a leading role in government seemed to many Social Democrats to sit rather uneasily alongside the verbal radicalism of their ideology. Unused to the experience of government, excluded from political participation for two generations before the war, they found the experience of collaborating with ‘bourgeois’ politicians a painful one. They could not rid themselves of their Marxist ideology without losing a large part of their electoral support in the working class; yet on the other hand a more radical policy, for example of forming a Red Army militia from workers instead of relying on the Free Corps, would surely have made their participation in bourgeois coalition governments impossible and called down upon their heads the wrath of the army.

The main strength of the Social Democrats lay in Prussia, the state that covered over half the territory of the Weimar Republic and contained 57 per cent of its population. Here, in a mainly Protestant area with great cities such as Berlin and industrial areas like the Ruhr, they dominated the government. Their policy was to make Prussia a bastion of Weimar democracy, and, although they did not pursue reforms with any great vigour or consistency, removing them from power in Germany’s biggest state became a major objective of Weimar democracy’s enemies by the early 1930s.

27

In the Reich, however, their position was far less dominant. Their strength at the beginning of the Republic owed a good deal to the support of middle-class voters who considered that a strong Social Democratic Party would offer the best defence against Bolshevism by effecting a quick transition to parliamentary democracy. As the threat receded, so their representation in the Reichstag went down, from 163 seats in 1919 to 102 in 1920. Despite a substantial recovery later on—153 seats in 1928, and 143 in 1930—the Social Democrats permanently lost nearly two and a half million votes, and, after receiving 38 per cent of the votes in 1919, they hovered around 25 per cent for the rest of the 1920s and early 1930s. Nevertheless, they remained an enormously powerful and well-organized political movement that claimed the allegiance and devotion of millions of industrial workers across the land. If any one party deserved to be called the bulwark of democracy in the Weimar Republic, it was the Social Democrats.