The Coming of the Third Reich (30 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

Eisner was everything the radical right in Bavaria hated: a bohemian and a Berliner, a Jew, a journalist, a campaigner for peace during the war, and an agitator who had been arrested for his part in the January strikes of 1918. Indeed, with his secretary, the journalist Felix Fechenbach, he even published secret and incriminating documents on the outbreak of the war from the Bavarian archives. He was, in short, the ideal object onto which the ‘stab-in-the-back’ legend could be projected. On 21 February 1919, the far right’s detestation found its ultimate expression as a young, aristocratic student, Count Anton von Arco-Valley, shot Eisner twice at point-blank range as he was walking through the street on his way to the Bavarian Parliament, killing him instantly.

4

The assassination unleashed a storm of violence in the Bavarian capital. Eisner’s guards immediately shot and wounded Arco-Valley, who was surrounded by an angry crowd; only Fechenbach’s prompt intervention saved him from being lynched on the spot. While the injured assassin was bundled off to the same cell in Stadelheim prison that Eisner had occupied only the year before, one of Eisner’s socialist admirers walked into the Parliament shortly afterwards, drew a gun, and in full view of all the other deputies in the debating chamber, fired two shots at Eisner’s severest critic, the Majority Social Democratic leader Erhard Auer, who barely survived his wounds. Meanwhile, ironically, a draft resignation document was discovered in Eisner’s pocket. The assassination had been completely pointless.

Afraid of further violence, however, the Bavarian Parliament suspended its meetings, and, without a vote, the Majority Social Democrats declared themselves the legitimate government. A coalition cabinet headed by an otherwise obscure Majority Social Democrat, Johannes Hoffmann, was formed, but it was unable to restore order as massive street demonstrations followed Eisner’s funeral. In the power vacuum that ensued, arms and ammunition were distributed to the workers’ and soldiers’ councils. News of the outbreak of a Communist Revolution in Hungary suddenly galvanized the far left into declaring a Council Republic in which Parliament would be replaced by a Soviet-style regime.

5

But the leader of the new Bavarian Council Republic was no Lenin. Once more, literary bohemianism had come to the fore, this time in the form of a dramatist rather than a critic. Only 25, Ernst Toller had made his name as a poet and, playwright. More of an anarchist than a socialist, Toller enrolled like-minded men in his government, including another playwright, Erich Mühsam, and a well-known anarchist writer, Gustav Landauer. Faced with the outspoken support of the Munich workers’ and soldiers’ councils for what Schwabing’s wits soon dubbed ‘the regime of the coffee house anarchists’, Hoffmann’s Majority Social Democratic cabinet fled to Bamberg, in northern Bavaria. Meanwhile, Toller announced a comprehensive reform of the arts, while his government declared that Munich University was open to all applicants except those who wanted to study history, which was abolished as hostile to civilization. Another minister announced that the end of capitalism would be brought about by the issue of free money. Franz Lipp, the Commissar for Foreign Affairs, telegraphed Moscow to complain that ‘the fugitive Hoffmann has taken with him the keys to my ministry toilet’, and declared war on Wurttemberg and Switzerland ‘because these dogs have not at once loaned me sixty locomotives. I am certain’, he added, ‘that we will be victorious.’

6

An attempt by the Hoffmann government to overthrow the Council Republic with an improvised force of volunteers was easily put down by the ‘Red Army’ recruited from the armed members of the workers’ and soldiers’ councils. Twenty men died in the exchanges of fire, however, and the situation was now clearly becoming much more dangerous. On the same day as the fighting took place, organized Communists under the Russian Bolsheviks Max Levien and Eugen Leviné pushed the ‘coffee house anarchists’ brusquely aside. Without waiting for the approval of the German Communist Party, they established a Bolshevik regime in Munich and opened communications with Lenin, who asked politely whether they had managed to nationalize the banks yet. Levien, who had been accidentally caught in Germany at the outbreak of war in 1914 and drafted into the German army, followed Lenin’s instructions, and began arresting members of the aristocracy and the upper middle class as hostages. While the main church in Munich was turned into a revolutionary temple presided over by the ‘Goddess Reason’, the Communists set about expanding and training a Red Army, which soon numbered 20,000 well-armed and well-paid men. A series of proclamations announced that Bavaria was going to spearhead the Bolshevization of Europe; workers had to receive military training, and all weapons in private possession had to be surrendered on pain of death.

7

All this frightened the Hoffmann government far more than the week-long regime of the coffee house anarchists had done. The spectre loomed of an axis of Bolshevik revolutionary regimes in Budapest, Munich and possibly Vienna as well. The Majority Social Democrats in Bamberg clearly needed a serious fighting force at their disposal. Hoffmann signed up a force of 35,000 Free Corps soldiers under the leadership of the Bavarian colonel Franz Ritter von Epp, backed by regular military units including an armoured train. They were equipped with machine guns and other serious military hardware. Munich was already in chaos, with a general strike crippling production, and public services at a standstill. Looting and theft were spreading across the city, and now it was blockaded by the Free Corps as well. No quarter would be given, they announced; anyone in Munich found bearing arms would immediately be shot. Terrified, the Munich workers’ and soldiers’ councils passed a vote of no-confidence in the Communists, who had to resign, leaving the city without a government. In this situation, a panicky unit of the Red Army began to take reprisals against hostages imprisoned in a local school, the Luitpold Gymnasium. These included six members of the Thule Society, an antisemitic, Pan-German sect, founded towards the end of the war. Naming itself after the supposed location of ultimate ‘Aryan’ purity, Iceland (‘Thule’), it used the ‘Aryan’ swastika symbol to denote its racial priorities. With its roots in the pre-war ‘Germanic Order’, another conspiratorial organization of the far right, it was led by the self-styled Baron von Sebottendorf, who was in reality a convicted forger known to the police as Adam Glauer. The Society. included a number of people who were to be prominent in the Third Reich.

8

It was known that Arco-Valley, the assassin of Kurt Eisner, had been trying to become a member of the Thule Society. In an act of revenge and desperation, the Red Army soldiers lined up ten of the hostages, put them in front of a firing squad, and shot them dead. Those executed included the Prince of Thurn and Taxis, the young Countess von Westarp and two more aristocrats, as well as an elderly professor who had been arrested for making an uncomplimentary remark in public about a revolutionary poster. A handful of prisoners taken from the invading Free Corps made up the rest.

The news of these shootings enraged the soldiers beyond measure. As they marched into the city, virtually unopposed, their victory became a bloodbath. Leading revolutionaries like Eugen Levine were arrested and summarily shot. The anarchist Gustav Landauer was taken to Stadelheim prison, where soldiers beat his face to a pulp with rifle butts, shot him twice, then kicked him to death in the prison courtyard, leaving the body to rot for two days before it was removed. Coming across a meeting of a Catholic craftsmen’s society on 6 May, a drunken Free Corps unit, told by an informer that the assembled workmen were revolutionaries, arrested them, took them to a nearby cellar, beat them up and killed a total of 21 of the blameless men, after which they rifled the corpses for valuables. Numerous other people were ‘shot trying to escape’, killed after being reported as former Communists, mown down after being denounced for supposedly possessing arms, or hauled out of houses from which shots had allegedly been fired, and executed on the spot. All in all, even the official estimates gave a total of some 600 killed at the hands of the invaders; unofficial observers made the total anything up to twice as high.

9

After the bloodbath, moderates such as Hoffmann’s Social Democrats, despite having commissioned the action, did not stand much of a chance in Munich. A ‘White’ counter-revolutionary government eventually took over, and proceeded to prosecute the remaining revolutionaries while letting off the Free Corps troops, a few of whom had been convicted for their murderous atrocities, with the lightest of sentences. Munich became a playground for extremist political sects, as virtually every social and political group in the city burned with resentment, fear and lust for revenge.

10

Public order had more or less vanished.

All this was deeply disturbing to the officers who were now faced with the task of reconstructing a regular army from the ruins of the old one. Not surprisingly, considering the fact that the workers’ and soldiers’ councils had enjoyed considerable influence amongst the troops, those who ran the new army were concerned to ensure that soldiers received the correct kind of political indoctrination, and that the many small political groups springing up in Munich posed no threat to the new, post-revolutionary political order. Among those who were sent to receive political indoctrination in June 1919 was a 30-year-old corporal who had been in the Bavarian army since the beginning of the war and had stayed in it through all the vicissitudes of Social Democracy, anarchy and Communism, taking part in demonstrations, wearing a red armband along with the rest of his comrades, and disappearing from the scene with most of them when they had been ordered to defend Munich against the invading forces in the preceding weeks. His name was Adolf Hitler.

11

II

Hitler was the product of circumstances as much as anything else. Had things been different, he might never have come to political prominence. At the time of the Bavarian Revolution, he was an obscure rank-and-file soldier who had so far played no part in politics of any kind. Born on 20 April 1889, he was a living embodiment of the ethnic and cultural concept of national identity held by the Pan-Germans; for he was not German by birth or citizenship, but Austrian. Little is known about his childhood, youth and upbringing, and much if not most of what has been written about his early life is highly speculative, distorted or fantastical. We do know, however, that his father Alois changed his name from that of his mother, Maria Schicklgruber, to whom he had been born out of wedlock in 1837, to that of his stepfather, Johann Georg Hiedler or Hitler, in 1876. There is no evidence that any of Hitler’s ancestors was Jewish. Johann Georg freely acknowledged his true paternity of Hitler’s father. Alois was a customs inspector in Braunau on the Inn, a minor but respectable official of the Austrian government. He married three times; Adolf was the only child of his third marriage to survive infancy apart from his younger sister Paula. ‘Psychohistorians’ have made much of Adolf’s subsequent allusions to his cold, stern, disciplinarian and sometimes violent father and his warm, much-loved mother, but none of their conclusions can amount to any more than speculation.

12

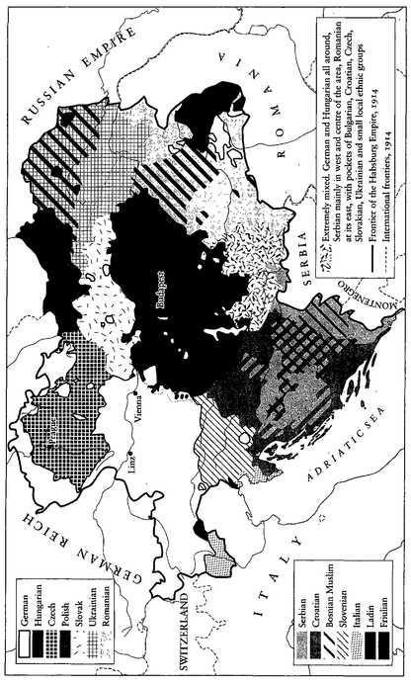

Map 6. Nationalities in the Hasburg Empire 1910

What is clear is that the Hitler family was often on the move, changing houses several times before settling in 1898 in a suburb of Linz, which Adolf ever after regarded as his home town. The young Hitler did poorly at school and disliked his teachers, but otherwise does not seem to have stood out amongst his fellow-pupils. He was clearly unfitted for the regular, routine life and hard work of the civil service, for which his father had intended him. After his father’s death early in 1903, he lived in a flat in Linz, where he was looked after by his mother, his aunt and his younger sister, and dreamed of making a future career as an artist while spending his time drawing, talking with friends, going to the opera and reading. But in 1907 two events occurred which put an end to this idle life of fantasizing. His mother died of breast cancer, and his application to the Viennese Academy of Art was rejected on the grounds that his painting and drawing were not good enough; he would do better, he was told, as an architect. Certainly, his forte lay in drawing and painting buildings. He was particularly impressed by the heavy, oppressive, historicist architecture of the public buildings on Vienna’s Ringstrasse, constructed as symbolic expressions of power and solidity at a time when the real political foundations of the Habsburg monarchy were beginning to crumble.

13

From the very beginning, buildings interested Hitler mainly as statements of power. He retained this interest throughout his life. But he lacked the application to become an architect. He tried again to join the Academy of Art, and was rejected a second time. Disappointed and emotionally bereft, he moved to Vienna. He took with him, in all probability, two political influences from Linz. The first was the Pan-Germanism of Georg Ritter von Schonerer, whose supporters in the town were particularly numerous, it seems, in the school that Hitler attended. And the second was an unquenchable enthusiasm for the music of Richard Wagner, whose operas he frequently attended in Linz; he was intoxicated by their romanticization of Germanic myth and legend, and by their depiction of heroes who knew no fear. Armed with these beliefs, and confident in his future destiny as a great artist, he spent the next five years in the Austrian capital.

14