The Coming of the Third Reich (51 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

FATEFUL DECISIONS

I

The Papen coup took place in the midst of Germany’s most frenetic and most violent election campaign yet, fought in an atmosphere even less rational and more vicious than that of two years before. Hitler once more flew across Germany from venue to venue, speaking before huge crowds at more than fifty major meetings, denouncing the divisions, humiliations and failures of Weimar and offering a vague but potent promise of a better, more united nation in the future. Meanwhile, the Communists preached revolution and announced the imminent collapse of the capitalist order, the Social Democrats called on the electors to rise up against the threat of fascism, and the bourgeois parties advocated a restorative unity they were patently unable to deliver.

138

The decay of parliamentary politics was graphically illustrated by the increasingly emotive propaganda style of the parties, including even the Social Democrats. Surrounded by increasingly violent street clashes and demonstrations, the political struggle became reduced to what the Social Democrats called - without the slightest hint of criticism - a war of symbols. Engaging a psychologist - Sergei Chakhotin, a radical Russian pupil of Pavlov, the discoverer of the conditioned response - to help them fight elections in the course of 1931, the Social Democrats realized that an appeal to reason was not enough. ‘We have to work on feelings, souls and emotions so that reason wins the victory.’ In practice, reason got left far behind. In the elections of July 1932 the Social Democrats ordered all their local groups to ensure that party members wore a party badge, used the clenched-fist greeting when encountering each other, and shouted the slogan ‘Freedom!’ at appropriate opportunities. In the same spirit, the Communists had long since been using the symbol of the hammer and sickle and a variety of slogans and greetings. In adopting this style, the parties were placing themselves on the same ground as the Nazis, with whose swastika symbol, ‘Hail Hitler!’ greeting and simple, powerful slogans they found it very difficult to compete.

139

Seeking for an image that would be dynamic enough to counter the appeal of the Nazis, the Social Democrats, the Reichsbanner, the trade unions, and a number of other working-class organizations connected with the socialists came together on 16 December 1931 to form the ‘Iron Front’ to fight the ‘fascist’ menace. The new movement borrowed heavily from the arsenal of propaganda methods developed by the Communists and the National Socialists. Long, boring speeches were to be replaced by short, sharp slogans. The labour movement’s traditional emphasis on education, reason and science was to yield to a new stress on the rousing of mass emotions through street processions, uniformed marches and collective demonstrations of will. The new propaganda style of the Social Democrats even extended to the invention of a symbol to counter that of the swastika and the hammer and sickle: three parallel arrows, expressing the three major arms of the Iron Front. None of this did much to help the traditional labour movement, many of whose members, not least those who occupied leading positions in the Reichstag, remained sceptical, or proved unable to adapt to the new way of presenting their policies. The new propaganda style placed the Social Democrats on the same ground as the Nazis; but they lacked the dynamism, the youthful vigour or the extremism to offer them effective competition. The symbols, the marches and the uniforms failed to rally new supporters to the Iron Front, since the entrenched organizational apparatus of the Social Democrats remained in control. On the other hand, it did not allay the fears of middle-class voters about the intentions of the labour movement.

140

Even more revealing were the election posters used by the parties in the campaigns of the early 1930s. A common feature to almost all of them was their domination by the figure of a giant, half-naked worker who had come by the late 1920s to symbolize the German people, replacing the ironically modest little figure of the ‘German Michel’ in his sleeping-cap or the more rarified female personification of

Germania

that had previously stood for the nation. Nazi posters showed the giant worker towering above a bank labelled ‘International High Finance’, destroying it with massive blows from a swastika-bedaubed compressor; the Social Democrats’ posters portrayed the giant worker elbowing aside Nazis and Communists; the Centre Party’s posters carried a cartoon of the giant worker, less scantily clad perhaps, but still with his sleeves rolled up, forcibly removing tiny Nazis and Communists from the parliament building; the People’s Party depicted the giant worker, dressed only in a loincloth, sweeping aside the soberly dressed politicians of all the other warring factions in July 1932, in an almost exact reversal of what was actually to happen in the elections; even the staid Nationalist Party used a giant worker in its posters, though only to wave the black-white-red flag of the old Bismarckian Reich.

141

All over Germany, electors were confronted with violent images of giant workers smashing their opponents to pieces, kicking them aside, yanking them out of parliament, or looming over frock-coated and top-hatted politicians who were almost universally portrayed as insignificant and quarrelsome pygmies. Rampant masculinity was sweeping aside the squabbling, ineffective and feminized political factions. Whatever the intention, the subliminal message was that it was time for parliamentary politics to come to an end: a message made explicit in the daily clashes of paramilitary groups on the streets, the ubiquity of uniforms at the hustings, and the non-stop violence and mayhem at electoral meetings.

None of the other parties could compete with the Nazis on this territory. Goebbels might have complained that ‘they are now stealing our methods from us’, but the three arrows had no deep symbolic resonance, unlike the familiar swastika. If the Social Democrats were to have stood any chance of beating the Nazis at their own game, they should have started earlier.

142

Goebbels fought the election not on the performance of the Papen cabinet but on the performance of the Weimar Republic. The main objects of Nazi propaganda this time, therefore, were the voters of the Centre Party and the Social Democrats. In apocalyptic terms, a flood of posters, placards, leaflets, films and speeches delivered to vast open-air assemblies, purveyed a drastic picture of the ‘red civil war over Germany’ in which voters were confronted with a stark choice: either the old forces of betrayal and corruption, or a national rebirth to a glorious future. Goebbels and his propaganda team aimed to overwhelm the electorate with an unremitting barrage of assaults on their senses. Saturation coverage was to be achieved not only by mass publicity but also by a concerted campaign of door-knocking and leafleting. Microphones and loudspeakers blasted out Nazi speeches over every public space that could be found. Visual images, purveyed not only through posters and magazine illustrations but also through mass demonstrations and marches in the streets, drove out rational discourse and verbal argument in favour of easily assimilated stereotypes that mobilized a whole range of feelings, from resentment and aggression to the need for security and redemption. The marching columns of the brownshirts, the stiff salutes and military poses of the Nazi leaders conveyed order and dependability as well as ruthless determination. Banners and flags projected the impression of ceaseless activism and idealism. The aggressive language of Nazi propaganda created endlessly repeated stereotypical images of their opponents - the ‘November criminals’, the ‘red bosses’, the ‘Jewish wire-pullers’, the ‘red murder-pack’. Yet, given the Nazis’ need to reassure the middle classes, the giant worker was now in some instances portrayed in a benevolent pose, no longer wild and aggressive, but wearing a shirt and handing tools of work to the unemployed instead of wielding them as weapons to destroy his opponents; the Nazis were prepared for responsible government.

143

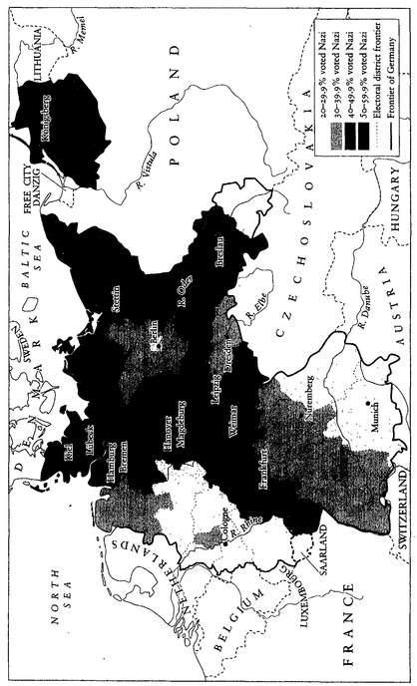

Map 14. The nazis in the Reichstag Election of july 1932

This unprecedentedly intense electoral propaganda soon brought its desired results. On 31 July 1932, the Reichstag election revealed the folly of Papen’s tactics. Far from rendering Hitler and the Nazis more amenable, the election brought them a further massive boost in power, more than doubling their vote from 6.4 million to 13.1 million and making them by far the largest party in the Reichstag, with 230 seats, nearly a hundred more than the next biggest group, the Social Democrats, who managed to limit their losses to 10 more seats and sent 133 deputies to the new legislature. The 18.3 per cent of the vote the Nazis had obtained in September 1930 was also more than doubled, to 37.4 per cent. The continued polarization of the political scene was marked by another increase for the Communists, who now sent 89 deputies to the Reichstag instead of 77. And while the Centre Party also managed to increase its vote and gain 75 mandates in the new parliament, its highest ever number, the Nationalists registered further losses, going down from 41 seats to 37, reducing them almost to the status of a fringe party. Most striking of all, however, was the almost total annihilation of the parties of the centre. The People’s Party lost 24 out of its 31 seats, the Economy Party 21 out of its 23, and the State Party, formerly the Democrats, 16 out of its 20. The congeries of far-right splinter-groups that had attracted such strong middle-class support in 1930 now also collapsed, retaining only 9 out of their previous 55 mandates. Left and right now faced each other in the Reichstag across a centre shrunken to insignificance: a combined Social Democrat/Communist vote of 13.4 million confronted a Nazi vote of 13.8 million, with all the other parties combined picking

up a

mere

9.8

million of the votes cast.

144

The reasons for the Nazis’ success at the polls in July 1932 were much the same as they had been in September 1930; nearly two more years of sharply deepening crisis in society, politics and the economy had rendered these factors even more powerful than they had been before. The election confirmed the Nazis’ status as a rainbow coalition of the discontented, with, this time, a greatly increased appeal to the middle classes, who had evidently overcome the hesitation they had displayed two years earlier, when they had turned to the splinter-groups of the right. Electors from the middle-class parties had by now almost all found their way into the ranks of Nazi Party voters. One in two voters who had supported the splinter-parties in September 1930 now switched to the Nazis, and one in three of those who had voted for the Nationalists, the People’s Party and the State Party in the previous Reichstag election. One previous non-voter in five now went to the polls to cast his or (especially) her vote for the Nazis. Even one in seven of those who had previously voted Social Democrat now voted Nazi. Thirty per cent of the Party’s gains came from the splinter-parties. These voters included many who had supported the Nationalists in 1924 and 1928. Even a few Communist and Catholic Centre Party voters switched, though this was roughly balanced out by those who switched back the other way. The Nazi Party continued to be attractive mainly to Protestants, with only 14 per cent of Catholic voters supporting it as against 40 per cent of non-Catholics. Sixty per cent of Nazi voters on this occasion were from the middle classes, broadly defined; 40 per cent were wage-earning manual workers and their dependants, though, as before, these were overwhelmingly workers whose connection with the labour movement, for a variety of reasons, had always been weak. The negative correlation between the size of the Nazi vote in any constituency, and the level of unemployment, was as strong as ever. The Nazis continued to be a catch-all party of social protest, with particularly strong support from the middle classes, and relatively weak support in the traditional industrial working class and the Catholic community, above all where there was a strong economic and institutional underpinning of the labour movement or Catholic voluntary associations.

145

Yet while July 1932 gave the Nazi Party a massive boost in the Reichstag, it was none the less something of a disappointment to its leaders. For them, the key factor in the result was not that they had improved on the previous Reichstag poll, but that they had not improved on their performance in the second round of the Presidential elections the previous March or the Prussian elections the previous April. There was a feeling, therefore, that the Nazi vote had finally peaked. In particular, despite a massive effort, the Party had only enjoyed limited success in its primary objective of breaking into the Social Democratic and Centre Party vote. So there was no repeat of the jubilation with which the Nazis had greeted their election victory of September 1930. Goebbels confided to his diary his feeling that ‘we have won a tiny bit’, no more. ‘We won’t get to an absolute majority this way,’ he concluded. The election therefore lent a fresh sense of urgency to the feeling that, as Goebbels put it, ‘something must happen. The time for opposition is over. Now deeds!’

146

The moment to grasp for power had arrived, he added the following day, and he noted that Hitler agreed with his view. Otherwise, if they stuck to the parliamentary route to power, the stagnation of their voting strength suggested that the situation might start to slip out of their grasp. Yet Hitler ruled out entering a coalition government led by another party, as indeed he was entitled to do, given the fact that his own Party now held by far the largest number of seats in the national legislature. Immediately after the election, therefore, Hitler insisted that he would only enter a government as Reich Chancellor. This was the only position that would preserve the mystique of his charisma amongst his followers. Unlike a subordinate cabinet position, it would also give him a good chance of turning dominance of the cabinet into a national dictatorship by using the full forces of the state that would then be at his disposal.