The Coming of the Third Reich (52 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

II

How those forces might be employed was graphically illustrated by an incident that occurred early in August 1932. In an attempt to master the situation, Papen had imposed a ban on public political meetings on 29 July. This merely had the effect of depriving activists of legitimate political outlets for their inflamed political passions. So it fuelled the violence on the streets. still further. On 9 August, therefore, he promulgated another emergency Presidential decree imposing the death penalty on anyone who killed an opponent in the political struggle out of rage or hatred. He intended this to apply above all to the Communists. But in the small hours of the following morning, a group of drunken brownshirts, armed with rubber truncheons, pistols and broken-off billiard cues, broke into a farm in the Upper Silesian village of Potempa and attacked one of the inhabitants, a Communist sympathizer, Konrad Pietzuch. The brownshirts struck him across the face with a billiard cue, beat him senseless, laid into him with their boots as he lay on the ground, and finished him off with a revolver. Pietzuch was Polish, making this into a racial as well as a political incident, and some of the brownshirts had a personal grudge against him. Nevertheless, it was clearly a political murder under the terms of the decree, and five of the brownshirts were arrested, tried and sentenced to death in the nearby town of Beuthen. As soon as the verdict was announced, brownshirted Nazi stormtroopers rampaged through the streets of Beuthen, wrecking Jewish shops and trashing the offices of liberal and left-wing newspapers. Hitler personally and publicly condemned the injustice of ‘this monstrous blood-verdict’, and Hermann Goring sent an open message of solidarity to the condemned ‘in boundless bitterness and outrage at the terror-judgment that has been served on you.’

147

The murder now became an issue in the negotiations between Hitler, Papen and Hindenburg over Nazi participation in the government. Ironically, President Hindenburg was in any case reluctant to accept Hitler as Chancellor because appointing a government led by the leader of the party that had won the elections would now look too much like going back to a parliamentary system of rule. Now he was dismayed by the Potempa murder, too. ‘I have had no doubts about your love for the Fatherland,’ he told Hitler patronizingly on 13 August 1933. ‘Against possible acts of terror and violence,’ he added, however, ‘as have, regrettably, also been committed by members of the SA divisions, I shall intervene with all possible severity.’ Papen, too, was unwilling to allow Hitler to lead the cabinet. After negotiations had broken down, Hitler declared:

German racial comrades! Anyone amongst you who possesses any feeling for the struggle for the nation’s honour and freedom will understand why I am refusing to enter this government. Herr von Papen’s justice will in the end condemn perhaps thousands of National Socialists to death. Did anyone think they could put my name as well to this blindly aggressive action, this challenge to the entire people? The gentlemen are mistaken! Herr von Papen, now I know what your bloodstained ‘objectivity’ is! I want victory for a nationalistic Germany, and annihilation for its Marxist destroyers and corrupters. I am not suited to be the hangman of nationalist freedom fighters of the German people!

148

Hitler’s support for the brutal violence of the stormtroopers could not have been clearer. It was enough to intimidate Papen, who had never intended his decree to apply to the Nazis, into commuting the condemned men’s sentences to life imprisonment on 2 September, in the hope of placating the leading Nazis,

149

Shortly after the incident, Hitler had sent the brownshirts on leave for a fortnight, fearing another ban. He need not have bothered.

150

Nevertheless, the Nazis, who had scented power after the July poll, were bitterly disappointed at the leadership’s failure to join the cabinet. The breakdown of negotiations with Hitler also left Papen and Hindenburg with the problem of gaining popular legitimacy. The moment for destroying the parliamentary system seemed to have arrived, but how were they to do it? Papen, with Hindenburg’s backing, determined to dissolve the new Reichstag as soon as it met. He would then use - or rather, abuse - the President’s power to rule by decree to declare that there would be no more elections. However, when the Reichstag finally met in September, amidst chaotic scenes, Hermann Goring, presiding over the session, according to tradition, as the representative of the largest party, deliberately ignored Papen’s attempts to declare a dissolution and allowed a Communist motion of no-confidence in the government to go ahead. The motion won the support of 512 deputies, with only 42 voting against and 5 abstentions. The vote was so humiliating, and demonstrated Papen’s lack of support in the country so graphically, that the plan to abolish elections was abandoned. Instead, the government saw little alternative but to follow the constitution and call a fresh Reichstag election for November.

151

The new election campaign saw Hitler, enraged at Papen’s tactics, launch a furious attack on the government. A cabinet of aristocratic reactionaries would never win the collaboration of a man of the people such as himself, he proclaimed. The Nazi press trumpeted yet another triumphant swing by ‘the Leader’ through the German states; but all its boasts of a massive turnout and wild enthusiasm for Hitler’s oratory could not disguise, from the Party leadership at least, the fact that many of the meeting-halls where Hitler spoke were now half-empty, and that the many campaigns of the year had left the Party in no financial condition to sustain its propaganda effort at the level of the previous election. Moreover, Hitler’s populist attacks on Papen frightened off middle-class voters, who thought they saw the Nazis’ ‘socialist’ character coming out again. Participation in a bitter transport workers’ strike in Berlin alongside the Communists in the run-up to the election did not help the Party’s image in the Berlin proletariat, although this had been Goebbels’ aim, and it also put off rural voters and repelled some middle-class electors, too. The once-novel propaganda methods of the Party had now become familiar to all. Goebbels had nothing left up his sleeve to startle the electorate with. Nazi leaders gloomily resigned themselves to the prospect of severe losses on polling day.

152

The mood amongst large parts of the Protestant middle classes was captured in the diary of Louise Solmitz, a former schoolteacher living in Hamburg. Born in 1899, and married to an ex-officer, she had long been an admirer of Hindenburg and Hugenberg, saw Brüning with typical Protestant disdain as a ‘petty Jesuit’, and complained frequently in her diary about Nazi violence.

153

But in April 1932 she had gone to hear Hitler speak at a mass meeting in a Hamburg suburb and had been filled with enthusiasm by the atmosphere and the public, drawn from all walks of life, as much as by the speech.

154

‘The Hitler spirit carries you away,’ she wrote, ‘is German, and right.’

155

All her family’s middle-class friends were supporting Hitler before long, and there was little doubt that they voted for him in July. But they were repelled both by Goring’s cavalier treatment of the Reichstag when it met, and by what they saw as the Nazis’ move to the left in the November election campaign. They now inclined more towards Papen, though never with much enthusiasm because he was a Catholic. ‘I’ve voted for Hitler twice,’ said an old friend, an ex-soldier, ‘but not any more.’ ‘It’s sad about Hitler,’ said another acquaintance: ‘I can’t go along with him any more.’ Hitler’s backing of the Berlin transport workers’ strike, Louise Solmitz thought, cost him thousands of votes. He was not interested in Germany, she concluded pessimistically, only in power. ‘Why has Hitler abandoned us, after he showed us a future which one could say yes to?’ she asked. In November the Solmitzes voted for the Nationalists.

156

Faced with this kind of disillusion, it was not surprising that the Nazis did badly. The election, on a much lower turnout than in July, registered a sharp fall in the Party’s vote, from 13.7 million to 11.7, reducing its representation in the Reichstag from 230 seats to 196. The Nazis were still by a very long way the largest party. But now they had fewer seats than the combined total of the two ‘Marxist’ parties.

157

‘Hitler in Decline’, the Social Democratic

Forwards

proclaimed.

158

‘We have suffered a set-back,’ confided Joseph Goebbels to his diary.

159

By contrast, the election registered some gains for the government. The Nationalists improved their representation from 37 to 51 seats, the People’s Party from 7 to 11. Many of their voters had returned from their temporary exile in the Nazi Party. But these were still miserably low figures, little more than a third of what the two parties had scored in their heyday in 1924. The pathetic decline of the former Democrats, the State Party, continued, as their representation went down from 4 seats to 2. The Social Democrats lost another 12 seats, taking them down to 121, their lowest figure since 1924. On the other hand the Communists, still the third largest party, continued to improve their position, gaining another 11 seats, which gave them a total of 100, not far behind the Social Democrats. For many middle-class Germans, this was a terrifyingly effective performance that threatened the prospect of a Communist revolution in the not-too-distant future. The Centre Party also saw a small decline, down from 75 seats to 70, with some of these votes going to the Nazis, as with their Bavarian wing, the Bavarian People’s Party.

160

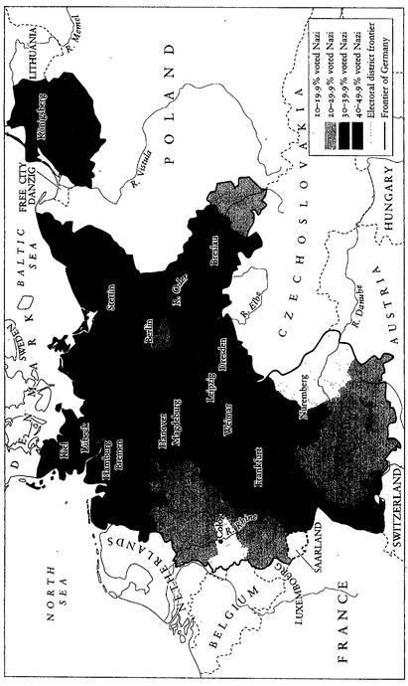

Map 15. The Nazis in the Reichstag Election of November 1932

Overall, the Reichstag was even less manageable than before. One hundred Communists now confronted 196 Nazis across the chamber, both intent on destroying a parliamentary system they hated and despised. As a result of the government’s rhetorical assault on them during the campaign, the Centre and the Social Democrats were more hostile to Papen than ever. Papen had completely failed to reverse his humiliation in the Reichstag on 12 September. He still faced an overwhelming majority against his cabinet in the new legislature. Papen considered cutting the Gordian knot by banning both Nazis and Communists and using the army to enforce a Presidential regime, bypassing the Reichstag altogether. But this was not a practical possibility, for by this point, fatally, he had lost the confidence of the army and its leading officers, too. Earlier in the year, the army hierarchy had pushed out the Minister of Defence, General Wilhelm Groener, finding his willingness to compromise with the Weimar Republic and its institutions no longer appropriate in the new circumstances. He was replaced by Schleicher, whose views were now more in tune with those of the leading officers. For his part, Schleicher was annoyed that the Chancellor had had the nerve to develop his own ideas and plans for an authoritarian regime instead of following the instructions of the man who had done so much to put him into power in the first place, that is, himself. Papen had also signally failed to deliver the parliamentary majority, made up principally of the Nazis and the Centre Party, that Schleicher and the army had been looking for. It was time for a new initiative. Schleicher quietly informed Papen that the army was unwilling to risk a civil war and would no longer give him its support. The cabinet agreed, and Papen, faced with uncontrollable violence on the streets and lacking any means of preventing its further escalation, was forced to announce his intention to resign.

161

III

Two weeks of complicated negotiations now followed, led by Hindenburg and his entourage. By this time, the constitution had in effect reverted to what it had been in the Bismarckian Reich, with governments being appointed by the head of state, without reference to parliamentary majorities or legislatures. The Reichstag had been pushed completely to the margins as a political factor. It was, in effect, no longer needed, not even to pass laws. Yet the problem remained that any government which tried to change the constitution in an authoritarian direction without the legitimacy afforded by the backing of a majority in the legislature would run a serious risk of starting a civil war. So the search for parliamentary backing continued. Since the Nazis would not play ball, Schleicher was forced to take on the Chancellorship himself on 3 December. His ministry was doomed from the start. Hindenburg resented his overthrow of Papen, whom he liked and trusted, and many of whose ideas he shared. For a few weeks, Schleicher, less hated by the Centre Party and the Social Democrats than Papen had been, earned a respite by avoiding any repetition of Papen’s authoritarian rhetoric. He continued to hope that the Nazis might come round. They had been weakened by the November elections and were divided over what to do next. Moreover, early in December, in local elections held in Thuringia, their vote plummeted by some 40 per cent from the previous July’s national high. A year of strenuous electioneering had also left the Party virtually bankrupt. Things seemed to be playing into Schleicher’s hands.

162