The Complete Yes Minister (65 page)

And Graham, not to be outdone, added with heavy sarcasm that it was not immediately apparent to him how Britain would benefit from a rapid deterioration of the road network.

Again I took a lead. I explained that I was merely trying to examine a few policy options for the government’s own freight transport needs. And that therefore I had thought that a preliminary chat with a few friends, advisers, around the table, could lead to some

positive, constructive

suggestions.

positive, constructive

suggestions.

I should not have wasted my breath. The positive constructive suggestions were somewhat predictable. Richard promptly suggested a firm commitment to rail transport, Graham a significant investment in motorway construction, and Piers a meaningful expansion of air freight capacity!

So at this point I explained that my overall brief is, among other things, to achieve an overall cut in expenditure.

‘In that case,’ said Richard grimly, ‘there is only one possible course.’

‘Indeed there is,’ snapped Graham.

‘And there can be no doubt what it is,’ Piers added in an icy tone.

They all eyed each other, and me. I was stuck. Sir Humphrey came to the rescue.

‘Good,’ he said with a cheerful smile, ‘I always like to end a meeting on a note of agreement. Thank you, gentlemen.’

And they filed out.

The meeting is the sort that would be described in a communiqué as ‘frank’. Or even ‘frank, bordering on direct’, which means that the cleaners have to mop up the blood in the morning.

SIR BERNARD WOOLLEY RECALLS:

4

4

The Minister found his meeting with the three Under-Secretaries confusing. This was because of his failure to understand the role of the Civil Service in making policy.

The three Under-Secretaries whom we met that morning were, in effect, counsel briefed by the various transport interests to resist any aspects of government policy that might have been unfavourable to their clients.

This is how the Civil Service in the 1980s actually worked in practice. In fact, all government departments – which in theory collectively represented the government to the outside world – in fact lobbied the government on behalf of their own client pressure group. In other words, each Department of State was actually controlled by the people whom it was supposed to be controlling.

Why – for instance – had we got comprehensive education throughout the UK? Who wanted it? The pupils? The parents? Not particularly.

The actual pressure came from the National Union of Teachers, who were the chief client of the DES.

5

So the DES went comprehensive.

5

So the DES went comprehensive.

Every Department acted for the powerful sectional interest with whom it had a permanent relationship. The Department of Employment lobbied for the TUC, whereas the Department of Industry lobbied for the employers. It was actually rather a nice balance: Energy lobbied for the oil companies, Defence lobbied for the armed forces, the Home Office for the police, and so on.

In effect, the system was designed to prevent the Cabinet from carrying out its policy. Well, somebody had to.

Thus a national transport policy meant fighting the

whole

of the Civil Service, as well as the other vested interests.

whole

of the Civil Service, as well as the other vested interests.

If I may just digress for a moment or two, this system of ‘checks and balances’, as the Americans would call it, makes nonsense of the oft-repeated criticism that the Civil Service was right wing. Or left wing. Or any other wing. The Department of Defence, whose clients were military, was – as you would expect – right wing. The DHSS, on the other hand, whose clients were the needy, the underprivileged and the social workers, was (predictably) left wing. Industry, looking after the Employers, was right wing – and Employment (looking after the

un

employed, of course) was left wing. The Home Office was right wing, as its clients were the Police, the Prison Service and the Immigration chaps. And Education, as I’ve already remarked, was left wing.

un

employed, of course) was left wing. The Home Office was right wing, as its clients were the Police, the Prison Service and the Immigration chaps. And Education, as I’ve already remarked, was left wing.

You may ask: What were we at the DAA? In fact, we were neither right nor left. Our main client was the Civil Service itself, and therefore our real interest was in defending the Civil Service against the Government.

Strict constitutional theory holds that the Civil Service should be committed to carrying out the Government’s wishes. And so it was, as long as the Government’s wishes were practicable. By which we meant, as long as

we

thought they were practicable. After all, how else can you judge?

we

thought they were practicable. After all, how else can you judge?

[

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

August 19th

Today Humphrey and I discussed Wednesday’s meeting.

And it was now clear to me that I had to get out of the commitment that I had made. Quite clearly, Transport Supremo is a title that’s not worth having.

I said to Humphrey that we had to find a way to force the PM’s hand.

‘Do you mean “we” plural – or do Supremos now use the royal pronoun?’

He was gloating. So I put the issue to him fair and square. I explained that I meant both of us, unless he wanted the DAA to be stuck with this problem.

As Humphrey clearly had no idea at all how to force the PM’s hand, I told him how it’s done. If you have to go for a politician’s jugular, go for his constituency.

I told Bernard to get me a map and the local municipal directory of the PM’s constituency.

Humphrey was looking puzzled. He couldn’t see what I was proposing to do. But I had to put it to him in acceptably euphemistic language. ‘Humphrey,’ I said, ‘I need your advice. Is it possible that implementing a national transport policy could have unfortunate local repercussions? Necessary, of course, in the wider national interest but painful to the borough affected!’

He caught on at once. ‘Ah. Yes indeed, Minister,’ he replied. ‘Inevitable, in fact.’ And he brightened up considerably.

‘And if the affected borough was represented in the House by a senior member of the government – a very senior member of the government – the

most

senior member of the government . . .?’

most

senior member of the government . . .?’

Humphrey nodded gravely. ‘Embarrassing,’ he murmured. ‘Deeply embarrasing.’ But his eyes were gleaming.

In due course Bernard obtained the street map of the PM’s constituency, and a street directory, and he found a relevant section in the business guide too. Once we studied the map, it was all plain sailing!

First we found a park. Humphrey noticed that it was near the railway station, and reminded me that one requirement of a national transport policy is to bring bus stations nearer to railway stations.

So, with deep regret, I made my first recommendation:

Build a bus station on Queen Charlotte’s Park

. Someone has to suffer in the national interest, alas!

Build a bus station on Queen Charlotte’s Park

. Someone has to suffer in the national interest, alas!

Second, we found a reference to a big bus repair shop, in the street directory. It seemed to us that it would be more economical to integrate bus and train repairs. There would undoubtedly be a great saving. So our second recommendation was

Close the bus repair shop

.

Close the bus repair shop

.

Then it struck me that the PM’s constituency is in commuter country. And we know, of course, that commuter trains run at a loss. They are only really used at rush hours. This means that commuters are, in effect, subsidised.

‘Is this fair?’ I asked Humphrey. He agreed that this was indeed an injustice to non-commuters. So we made our third recommendation:

Commuters to pay full economic fares

.

Commuters to pay full economic fares

.

Sadly this will double the price of commuter tickets, but you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.

6

6

Humphrey noted that the PM’s constituency contained several railway stations – British Rail as well as the Underground. He reminded me that some people take the view that areas with reasonable rail services don’t need an evening bus service as well. I regard this as an extremely persuasive view. Accordingly, we made our fourth recommendation.

Stop all bus services after 6.30 p.m

.

Stop all bus services after 6.30 p.m

.

We then moved on to consider what to do with all the remaining land after the removal of the bus station into the park.

We had to rack our brains on this matter for a while, but eventually we realised that the whole area seemed very short of parking space for container lorries. Especially at night. So fifth we recommended:

Container lorry park on bus station site

.

Container lorry park on bus station site

.

Regretfully, on closer study, the map revealed that building a new container lorry park would mean widening the access road. Indeed, it appears that the western half of the swimming baths might have to be filled in. But we could see no alternative:

Widen the access road to the bus station site

was our sixth and last recommendation.

Widen the access road to the bus station site

was our sixth and last recommendation.

We sat back and considered our list of recommendations. These had nothing whatever to do with the PM personally, of course. They were simply the local consequences of the broad national strategy.

However, I decided to write a paper which would be sent to Number Ten for the PM’s personal attention. The PM would undoubtedly wish to be informed of the constituency implications and as a loyal Minister and dutiful colleague I owe this to the PM. Among other things!

Humphrey raised one other area of concern. ‘It would be awful, Minister, if the press got hold of all this. After all, lots of other boroughs are likely to be affected. There’d be a national outcry.’

I asked if he thought there was any danger of the press getting hold of the story.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘they’re very clever at getting hold of things like this. Especially if there’s lots of copies.’

A good point. Humphrey’s a bloody nuisance most of the time, but I must say that he’s a good man to have on your side in a fight.

‘Oh dear,’ I replied. ‘This

is

a problem, because I’ll have to copy all my Cabinet colleagues with this note. Their constituencies are bound to be affected as well, of course.’

is

a problem, because I’ll have to copy all my Cabinet colleagues with this note. Their constituencies are bound to be affected as well, of course.’

Humphrey reassured me on this point. He said that we must hope for the best. If it

were

leaked, with all those copies, no one could

ever

discover who leaked it. And as it happened, he was lunching today with Peter Martell of

The Times

.

were

leaked, with all those copies, no one could

ever

discover who leaked it. And as it happened, he was lunching today with Peter Martell of

The Times

.

I found this very reassuring.

I told him not to do anything that I wouldn’t do. He told me that I could rely on him.

I’m sure I can.

I wonder how he got on.

[

Sir Humphrey’s account of lunch with Peter Martell has been found in his private diary – Ed

.]

Sir Humphrey’s account of lunch with Peter Martell has been found in his private diary – Ed

.]

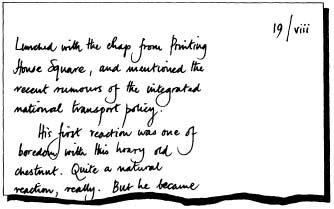

Lunched with the chap from Printing House Square, and mentioned the recent rumours of the integrated national transport policy.

His first reaction was one of boredom with this hoary old chestnut. Quite a natural reaction, really. But he became interested when I hinted of the rumours that the policy may have several unwelcome side-effects.

Job loss from integration of the railway terminals.

Job loss from joint repair shops.

Job loss from streamlining of services.

Reduction of bus and train services – causing job loss.

Peter realised that this could be rather a large story, especially in view of the rumours that one of the areas to suffer most will be the PM’s own constituency. I can’t imagine how these rumours got around.

He asked for hard facts, and I admonished him. He persisted, explaining to me that newspapers are not like the Government – if they make statements they have to be able to prove that they are true.

He pressed me for news of a White Paper or a Green Paper. I gave no help. But I did have to confirm that there is in existence a confidential note from Hacker to the PM with similar notes to all twenty-one of his Cabinet colleagues.

‘Oh that’s all right then,’ he said cheerfully. ‘Are

you

going to show it to me or shall I get it from one of your colleagues?’

you

going to show it to me or shall I get it from one of your colleagues?’

I reproved him. I explained that it was a confidential document. It would be grossly improper to betray it to anyone, let alone a journalist.

The only way he could possibly obtain a copy of such a document would be if somebody left it lying around by mistake. The chances of that happening are remote, of course.

[

It seems, from Sir Humphrey’s account, that he even wrote his private diary in such a way as to prevent it being used as evidence against him. But Peter Martell’s subsequent publication of the full details of the confidential note, only one day later, suggests that Sir Humphrey had carelessly left his own copy lying around – Ed

.]

It seems, from Sir Humphrey’s account, that he even wrote his private diary in such a way as to prevent it being used as evidence against him. But Peter Martell’s subsequent publication of the full details of the confidential note, only one day later, suggests that Sir Humphrey had carelessly left his own copy lying around – Ed

.]

August 22nd

Humphrey did his job well. The full disclosure of my seven-point plan for the Prime Minister’s constituency appeared in

The Times

on Saturday. I must say I had a jolly good laugh about it. By 10.30 a.m. I’d received the expected summons for a chat with Sir Mark Spencer at Number Ten. (The PM’s still abroad.)

The Times

on Saturday. I must say I had a jolly good laugh about it. By 10.30 a.m. I’d received the expected summons for a chat with Sir Mark Spencer at Number Ten. (The PM’s still abroad.)

I went this morning, and M.S. came straight to the point.

‘I thought I ought to tell you that the PM isn’t very pleased.’ He waved Saturday’s

Times

at me. ‘This story.’

Times

at me. ‘This story.’

Other books

A Cold Day in Hell (An Erotic Paranormal Short Story) by D'Amore, Deni

Warriors in Paradise by Luis E. Gutiérrez-Poucel

Rock Killer by S. Evan Townsend

Which Way to the Wild West? by Steve Sheinkin

Two More Pints by Roddy Doyle

The Forsaken by Ace Atkins

Sealed with a Kiss by Mae Nunn

Adela's Prairie Suitor (The Annex Mail-Order Brides Book 1) by Elaine Manders

The Alley by Eleanor Estes

La paja en el ojo de Dios by Jerry Pournelle & Larry Niven