The Complete Yes Minister (77 page)

He didn’t know how to reply to that. ‘I, er, I hardly think so,’ he said, damning himself further.

I agreed, and said that I sincerely hoped that anyone who made a howler like that could

never

go on to be a Permanent Secretary. He nodded, but the expression on his face looked as though his teeth were being pulled out without an anaesthetic.

never

go on to be a Permanent Secretary. He nodded, but the expression on his face looked as though his teeth were being pulled out without an anaesthetic.

‘But it was so long ago,’ he said. ‘We can’t find out that sort of thing now.’

And then I went for the jugular. This was the moment I’d been waiting for. Little did I dream, after he had humiliated me in front of Richard Cartwright, that I would be able to return the compliment so soon.

And with the special pleasure of using his own arguments on him.

‘Of course we can find out,’ I said. ‘You were telling me that everything is minuted and full records are always kept in the Civil Service. And you were quite right. Well, legal documents concerning a current lease could not possibly have been thrown away.’

He stood. Panic was overcoming him. He made an emotional plea, the first time I can remember him doing such a thing. ‘Minister, aren’t we making too much of this? Possibly blighting a brilliant career because of a tiny slip thirty years ago. It’s not such a lot of money wasted.’

I was incredulous. ‘Forty million?’

‘Well,’ he argued passionately, ‘that’s not such a lot compared with Blue Streak, the TSR2, Trident, Concorde, high-rise council flats, British Steel, British Rail, British Leyland, Upper Clyde Ship Builders, the atomic power station programme, comprehensive schools, or the University of Essex.’

[

In those terms, his argument was of course perfectly reasonable – Ed

.]

In those terms, his argument was of course perfectly reasonable – Ed

.]

‘I take your point,’ I replied calmly. ‘But it’s still over a hundred times more than the official in question can have earned in his entire career.’

And then I had this wonderful idea. And I added: ‘I want you to look into it and find out who it was, okay?’

Checkmate. He realised that there was no way out. Heavily, he sat down again, paused, and then told me that there was something that he thought I ought to know.

Surreptitiously I reached into my desk drawer and turned on my little pocket dictaphone. I wanted his confession to be minuted. Why not? All conversations have to be minuted. Records must be kept, mustn’t they?

This is what he said. ‘The identity of this official whose alleged responsibility for this hypothetical oversight has been the subject of recent speculation is not shrouded in quite such impenetrable obscurity as certain previous disclosures may have led you to assume, and, in fact, not to put too fine a point on it, the individual in question was, it may surprise you to learn, the one to whom your present interlocutor is in the habit of identifying by means of the perpendicular pronoun.’

‘I beg your pardon?’ I said.

There was an anguished pause.

‘It was I,’ he said.

I assumed a facial expression of deep shock. ‘Humphrey! No!’

He looked as though he was about to burst into tears. His fists clenched, knuckles whitened. Then he burst out. ‘I was under pressure! We were overworked! There was a panic! Parliamentary questions tabled.’ He looked up at me for support. ‘Obviously I’m not a trained lawyer, or I wouldn’t have been in charge of the legal unit.’

[

True enough. This was the era of the generalist, in which it would have seemed sensible and proper to put a classicist in charge of a legal unit or a historian in charge of statistics – Ed

.] ‘Anyway – it just happened. But it was thirty years ago, Minister. Everyone makes mistakes.’

True enough. This was the era of the generalist, in which it would have seemed sensible and proper to put a classicist in charge of a legal unit or a historian in charge of statistics – Ed

.] ‘Anyway – it just happened. But it was thirty years ago, Minister. Everyone makes mistakes.’

I was not cruel enough to make him suffer any longer. ‘Very well Humphrey,’ I said in my most papal voice. ‘I forgive you.’

He was almost embarrassingly grateful and thanked me profusely.

I expressed surprise that he hadn’t told me. ‘We don’t have any secrets from each other, do we?’ I asked him.

He didn’t seem to realise that I had my tongue in my cheek. Nor did he give me an honest answer.

‘That’s for you to say, Minister.’

‘Not entirely,’ I replied.

Nonetheless, he was clearly in a state of humble gratitude and genuinely ready to creep. And now that he was so thoroughly softened up, I decided that this was the moment to offer my

quid pro quo

.

quid pro quo

.

‘So what do I do about this?’ I asked. ‘I’ve promised to let

The Mail

see all the papers. If I go back on my word I’ll be roasted.’ I looked him straight in the eye. ‘On the other hand, I might be able to do something if I didn’t have this other problem on my plate.’

The Mail

see all the papers. If I go back on my word I’ll be roasted.’ I looked him straight in the eye. ‘On the other hand, I might be able to do something if I didn’t have this other problem on my plate.’

He knew only too well what I was saying. He’s done this to me often enough.

So, immediately alert, he asked me what the other problem was.

‘Being roasted by the press for disciplining the most efficient council in Britain.’

He saw the point at once, and adjusted his position with commendable speed.

After only a momentary hesitation he told me that he’d been thinking about South-West Derbyshire, that obviously we can’t change the law as such, but that it might be possible to show a little leniency.

We agreed that a private word to the Chief Executive would suffice for the moment, giving them a chance to mend their ways.

I agreed that this would be the right way to handle the council. But it still left one outstanding problem: how would I explain the missing papers to

The Mail

?

The Mail

?

We left it there. Humphrey assured me that he would give the question his most urgent and immediate attention.

I’m sure he will. I look forward to seeing what he comes up with tomorrow.

November 23rd

When I arrived at the office this morning Bernard informed me that Sir Humphrey wished to see me right away.

He hurried in clutching a thin file, and looking distinctly more cheerful.

I asked him what the answer was to be.

‘Minister,’ he said, ‘I’ve been on to the Lord Chancellor’s Office, and this is what we normally say in circumstances like this.’

He handed me the file. Inside was a sheet of paper which read as follows:

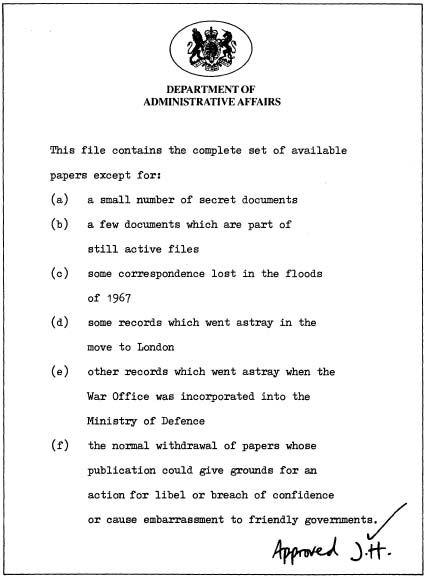

‘This file contains the complete set of available papers except for:

(a)

a small number of secret documents

(b)

a few documents which are part of still active files

(c)

some correspondence lost in the floods of 1967

(d)

some records which went astray in the move to London

(e)

other records which went astray when the War Office was incorporated into the Ministry of Defence

(f)

the normal withdrawal of papers whose publication could give grounds for an action for libel or breach of confidence or cause embarrassment to friendly governments.’

[

1967 was, in one sense, a very bad winter. From the Civil Service point of view it was a very good one. All sorts of embarrassing records were lost – Ed

.]

1967 was, in one sense, a very bad winter. From the Civil Service point of view it was a very good one. All sorts of embarrassing records were lost – Ed

.]

I read this excellent list. Then I looked in the file. There were no papers there at all! Completely empty.

‘Is

this

how many are left? None?’

this

how many are left? None?’

‘Yes Minister.’

1

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

2

Rat-catchers.

Rat-catchers.

3

Brand of sleeping pills in common use in the 1980s.

Brand of sleeping pills in common use in the 1980s.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781446416488

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by BBC Books

An imprint of BBC Worldwide Ltd.

Woodlands, 80 Wood Lane,

London W12 0TT

First published in three volumes

in paperback 1981, 1982, 1983

Revised omnibus edition

first published in hardback 1984

This paperback omnibus edition

first published 1989

© Jonathan Lynn and Antony Jay

1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1989

ISBN-10: 0-563-20665-9

ISBN-13: 978-0-563-20665-1

Other books

Harvest of Bones by Nancy Means Wright

Bad Games by Jeff Menapace

Something for the Pain (Pain #2) by Victoria Ashley

Jaded 2: Broken Love Series by Renee Tyler

Aphrodite's Garden (A Fast Break Romance) by Staley, Deborah Grace

Britt-Marie Was Here by Fredrik Backman

How to Be Bad by David Bowker

El redentor by Jo Nesbø

Slam: A Bad Boy Romance by Holt, Leah