The Conquering Tide (28 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

R

ADIO MONITORS ON THE

Y

AMATO

had picked up a United Press report, broadcast from Hawaii, referring to plans in the making for “a major sea and air battle soon near the Solomons.”

5

It did not escape Admiral Ugaki's attention that Americans were about to go to the polls for midterm congressional elections. Would FDR order a major operation to coincide with America's Navy Day (October 27), in hopes of stirring up voter support for

his party? That chain of reasoning was badly flawed, but the Combined Fleet staff had nonetheless surmised correctly that Halsey would throw all available naval forces into the defense of Guadalcanal. The Japanese army and navy gathered strength for an all-out sea-air-ground offensive, with the dual ambitions of seizing Henderson Field and wiping out the American fleet.

The Japanese fleet was the largest assembled since the Midway offensive: two fleet carriers, two light carriers, and four battleships, with many supporting cruisers, destroyers, and auxiliaries, sixty-one ships altogether. As at Midway, the Japanese plan called for a partition of naval forces into several, widely separated groups. The advance or van of the Japanese fleet would be led by Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo, who flew his flag in the cruiser

Atago

, and would include two battleships, five cruisers, ten destroyers, and a light flattop, the

Junyo

. A scouting line (and decoy force) of surface warships and one light carrier would steam about a hundred miles ahead of the two big fleet carriers,

Shokaku

and

Zuikaku

. As in the August battle, the Japanese commanders hoped that the Americans' initial carrier airstrike would fall on the scouting line. The various elements would converge on Guadalcanal after the Japanese army had broken through Vandegrift's perimeter and overrun the airfield.

The Japanese army was in force on Guadalcanal, but it continued to operate under the heavy disadvantages of poor communications and the rigors of an unforgiving jungle terrain. The scheduled assault on Vandegrift's lines was twice delayed (from October 22 to October 24, local date), and when it began, it quickly deteriorated into a series of small, confused unit encounters. The marines held their well-fortified lines and exacted a bloody toll on the attackers, who suffered casualties at the ratio of about seven to one. At dawn on the morning of October 25, however, a Japanese soldier thought he saw green-white flares over Henderson, the agreed signal that the airfield had been captured, and the Japanese army radioed the defective information to Rabaul. It was relayed to Ugaki and Yamamoto, and the

Yamato

's towering radio antennae told Kondo and Nagumo to charge south toward the island and seek battle with the American fleet. The advance force passed through Indispensable Strait, north of Malaita. There it was intercepted by five SBDs from Guadalcanal, which planted bombs on a destroyer and a light cruiser, the

Yura

. The ships turned tail and ran, leaving the stricken

Yura

to be abandoned and scuttled.

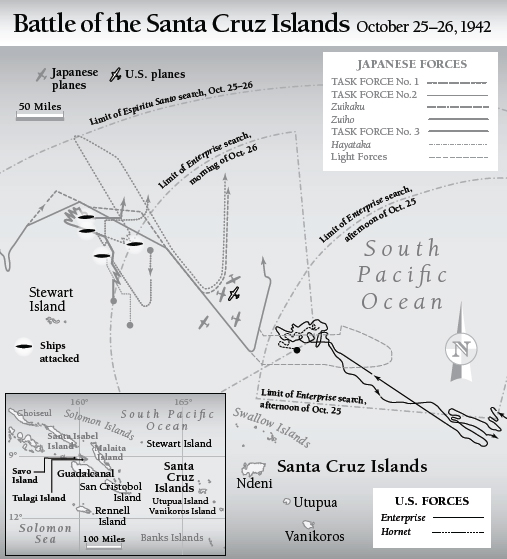

Task Force 61 had meanwhile advanced along the northern shoals of the Santa Cruz group, and then turned southwest toward a point just east of San Cristobal. Throughout the long daylight hours of October 25, the two fleets steamed toward one another as air patrols reached out and probed ahead. A PBY spotted two big Japanese carriers at 11:03 a.m., but in a position 355 nautical miles from Task Force 61, far out of range. At 12:50 p.m., the seaplane tender

Curtiss

relayed a sighting report from one of her seaplanes, reporting two Japanese carriers to the northwest, 360 miles away. Closing on the enemy at near-maximum speed, Kinkaid made the chancy decision to launch a twenty-nine-plane composite strike. The planes went out to the

end of their search vectors, continued eighty miles to the northwest, and finally turned back in the failing light. The F4F pilots of Fighting Squadron Ten flew for three and a half hours at 17,000 feet, exhausting themselves, their oxygen supply, and their fuel.

6

As they spiraled down through broken cloud cover, the

Enterprise

was nowhere to be seen. Running on fumes, they descended to just 15 to 20 feet above the sea, until Swede Vejtasa caught sight of an oil slick reflected in his own running lights. The Wildcats followed that greasy trail for forty-five miles and found the ship.

7

Several were forced to ditch at sea due to fuel exhaustion, or crashed while trying to land on the

Enterprise

in darkness.

8

A full moon rose in the east and threw enough light across the sea to accommodate nighttime air searches. PBYs from Ndeni continued to blanket the area. At 3:10 a.m., one spotted the long, darkened flight deck of the

Zuikaku

. Kinkaid cocked his air group for a night bombing attack, and the aircrews remained in their ready rooms all night. But without further confirmation of the enemy fleet's position, the admiral prudently chose to keep the strike on deck until dawn.

At first light on October 26, the two groups were only about 200 miles apart. The weather was fair, with clear visibility above and below a 2,000-foot layer of scattered cumulus and stratocumulus clouds. The sea was smooth and the northwest breeze less than 10 knots.

9

Passing rainsqualls would continue throughout the day. Two Dauntlesses of Kinkaid's morning search flight discovered the

Zuiho

at 7:40 a.m. and attacked her directly. Both dive-bombers scored, pitching their 500-pound bombs into the middle of her flight deck. The little flattop survived but could neither launch nor recover aircraft for the remainder of the battle.

10

About ten minutes later, some miles north, two more

Enterprise

SBDs discovered the

Shokaku

and

Zuikaku

. They radioed the contact report and prepared to dive, but defending Zeros broke up the attack. Both planes escaped by dodging into a cloud bank.

Nagumo and Kinkaid now hurled their principal airstrikes at one another. Strung out over fifty or sixty miles in three separated groups, the American planes were vulnerable to the concentrated attentions of the Zeros passing on a reciprocal heading. Nine Japanese fighters dived unseen out of the sun on the

Enterprise

torpedo planes of VT-10, and sent three TBFs down in flames before the American aircrews had even registered the

enemy's presence.

11

Misleading oddments of radio chatter confused and misled aviators in the trailing squadrons. The surviving

Enterprise

Avengers had lost altitude in their tussle with the Zeros, thus shrinking their visible horizon. Finding no carriers, they attacked the

Chikuma

, inflicting heavy damage on the Japanese cruiser but failing to sink her.

12

At 10:50, the first wave of

Hornet

planes converged on the

Shokaku

. Lieutenant Commander William J. “Gus” Widhelm, commander of the

Hornet

's VS-8, kept his tracers centered on a Zero coming directly toward him in a head-on run and blew the plane apart, then dived sharply to evade the oncoming debris. A second Zero darted in from a high side and fired two or more 20mm rounds into his engine with a full deflection shot. Widhelm's engine emitted black oil smoke, then seized, and he dropped out of the battle. (He ditched safely and was recovered later with his radio-gunner, George D. Stokely.) Though he had been roughly handled by the Zeros, Widhelm's determination to manage his aircraft like a fighter rather than a dive-bomber had diverted the enemy's attention from the remaining

Hornet

SBDs, which reached their attacking positions and pushed into their dives.

13

The

Shokaku

, according to a VB-8 radio-gunner, was lit up all along her length by antiaircraft fire, “like a Christmas tree,”

14

but the Dauntlesses plunged through the flak and released their 1,000-pound armor-piercing bombs. Three smashed through the flight deck and exploded in the interior of the ship, with spectacularly destructive effect.

15

From the bridge of a screening destroyer, Captain Tameichi Hara saw “two or three silver streaks, which appeared like thunderbolts, reaching toward the bulky carrier. . . . The whole deck bulged quietly and burst. Flames shot from the cleavages. I groaned as the flames rose and black and white smoke came belching out of the deck.”

16

By 10:30 a.m., the Americans had knocked two Japanese carriers out of action, an impressive score even if neither ship was destroyed. In the meantime, however, more than a hundred Japanese planes were converging on the

Hornet

and

Enterprise

. The American radar sets first detected the incoming Japanese strike at 9:05 a.m., and the task force raised speed for evasive maneuvering. The combat air patrol first made contact with the enemy planes at 9:59, when they were at 17,000 feet altitude, about forty miles northwest of the task force. The

Enterprise

managed to take cover in a passing rainsquall, but her disappearance diverted the full brunt of the enemy air attack to the

Hornet

.

“Stand by for dive bombing attack,” warned the

Hornet

's loudspeakers at 9:09, and down came a long convoy of steeply diving Aichi “Val” dive-bombers. Tearing through the sea at 28 knots, the carrier S-turned radically and her antiaircraft guns threw up a dense barrage, but several planes made accurate releases at the near-suicidal altitude of 800 feet. Three 250-kilogram bombs crashed through the

Hornet

's flight deck in quick succession and exploded in the lower decks. A damaged Aichi dived vertically into the island, its pilot apparently determined to trade his life for a chance to destroy the ship's brain center. The burning plane glanced off the stack, sheered through the signal bridge, and crashed into the flight deck amidships.

17

Saturated with burning aviation gasoline, the

Hornet

's entire superstructure burst into flames. According to Alvin Kernan, stationed in a repair shack just below the island, “a bright red flame came like an express train down the passageway, throwing everything and everybody flat.”

18

At about the same time, low-flying Japanese torpedo planes approached on the starboard and port sides simultaneously. They attempted to fly over or around the screening ships to get to the

Hornet

. One of the

South Dakota

's 40mm quad mounts destroyed an oncoming Nakajima when it was just thirty yards awayâ“sawed the wing right off it,” a witness recalled.

19

Another enemy plane hopped over the

South Dakota

and crashed, apparently deliberately, into the port side of the

Hornet

. Burning wreckage skittered across the flight deck and fell into the No. 1 elevator pit.

20

Two aerial torpedoes slammed into the wounded carrier's starboard side, lifting the entire hull and shaking it violently. Propulsion, fire main pressure, power, and internal communications were lost, and the

Hornet

listed 10 degrees to starboard.

21

At 9:50, the

Enterprise

CXAM radar detected a second wave of incoming enemy dive-bombers. The

Enterprise

and her nearby escorts put up a prodigious barrage and destroyed half the Aichis in that first dive, but the survivors pressed the attack with skill and determination and planted three bombs on the flight deck. The first struck near the bow, destroying one airplane and ejecting another off the

Enterprise

, then punched through four layers of steel plating before detonating just outside the bow.

22

A second hit just aft of the forward elevator on the centerline of the flight deck and exploded below the hangar deck. A third bomb was a near miss to starboard, causing the entire ship to shudder and tossing another plane overboard.

Those heavy blows did not slow the

Enterprise

at all, and even while

maneuvering radically, the ship somehow managed to recover several of her returning planes. But the second explosion jammed her forward elevator in the up position, reducing her plane-handling capabilities by at least 50 percent. Damage-control parties put hoses on the fire and fitted steel plates over the holes on the flight deck. The hangar was a mess, howeverâthe entire deck was bulged upward and strewn with bodies and parts of bodies and blazing aircraft wreckage.

Fifteen dark-green “Kate” torpedo planes approached the

Enterprise

at 11:35. They divided into two groups and maneuvered to set up an “anvil attack” on both bows. Captain Osborne B. Hardison ordered the helm hard right, turning the

Enterprise

toward one group and leaving the other far astern. Floyd Beaver watched from the signal bridge as the second group attempted to overtake the ship, flying parallel on the beam at about 1,500 yards' range, “strung out like tin ducks in a shooting gallery.”

23

The 40mm Bofors quadruple-barrel mounts cut them down methodically, one by one. The second group released their torpedoes, and Hardison deftly turned the ship toward the oncoming tracks and threaded them neatly. Men in the port gun galleries looked down and watched one of the long black cylindrical shapes speed away in the opposite direction, just beneath the surface. At 12:20, the injured

Enterprise

took cover in another passing rainsquall.

24