The Conquering Tide (38 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

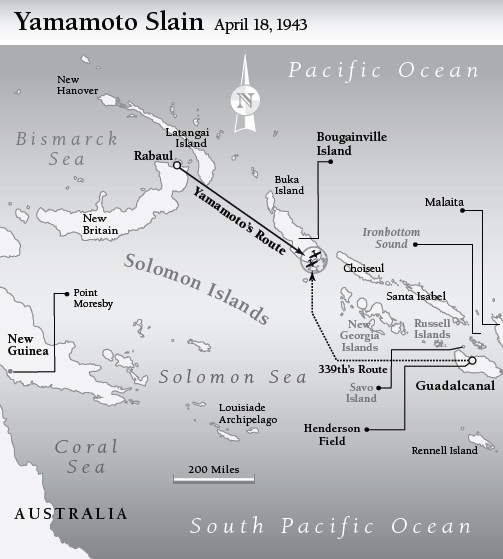

Ugaki nodded off as the group began its descent toward Ballale. At 9:43 a.m., he awoke to find his plane in a steep diving turn. The pilot was unsure of what was happening, but the sudden evasive maneuvers of the escorting Zeros had alerted him that something was awry. The dark green canopy of

the jungle hills reached up toward them. The gunners opened up the gun ports to prepare for firing, and between the wind blowing in and the sound of the machine guns, things got very noisy. Ugaki told the pilot to try to remain with Yamamoto's plane, but it was too late; as his plane banked south, he caught a glimpse of his chief's plane “staggering southward, just brushing the jungle top with reduced speed, emitting black smoke and flames.” His view was again obscured, and the next time he looked, there was only a column of smoke rising from the jungle.

84

Ugaki's pilot flew over Cape Moira and out to sea, descending steadily to gain speed. Two Lightnings were in close pursuit, however, and .50-caliber rounds began slamming into the wings and fuselage. The pilot tried to pull up, but his propellers dug into the sea and the plane rolled hard to the left. Ugaki was thrown from his seat and slammed against an interior bulkhead. As the water entered the sinking aircraft, he thought, “This is the end of Ugaki.”

85

Somehow, however, he and three other passengers managed to get free and swim toward the beach. They were helped ashore by Japanese soldiers and transported to Buin.

Yamamoto's plane had gone down about four miles inland, in remote jungle. Search parties took more than a day to find the site. There were no survivors. Yamamoto, according to eyewitnesses, was sitting upright, still strapped into his seat, with one white-gloved hand resting on his sword. A bullet had entered his lower jaw and emerged from his temple; another had pierced his shoulder blade. His corpse was wrapped in banyan leaves and carried down a trail to the mouth of the Wamai River, where it was taken to Buin by sea. There it was cremated in a pit filled with brushwood and gasoline. The ashes were flown back to Truk and deposited on a Buddhist altar in the

Musashi

's war operations room.

News of Yamamoto's death was at first restricted to a small circle of ranking officers, and passageways around the operations room and the commander in chief's cabin were placed off limits. But the truth soon leaked out to the

Musashi

's crew. Admiral Ugaki was seen in bandages; the white box containing Yamamoto's ashes was glimpsed as it was carried on board; and the smell of incense wafted from his cabin. Admiral Mineichi Koga was quickly named the new commander in chief, and flew in from Japan on April 25. At last an announcement was made to the crew. In Japan the news was kept under wraps for more than a month.

On May 22, Yamamoto's death led the news on NHK, Japan's national

radio network. The announcer broke into tears as he read the copy. A special train carried the slain admiral's ashes from Yokosuka to Tokyo. An imperial party, including members of the royal household and family, greeted its arrival at Ueno Station. Diarist Kiyoshi Kiyosawa noted, “There is widespread sentiment of dark foreboding about the future course of the war.”

86

On June 5, 1943, the first anniversary of the Battle of Midway, a grand state funeral was held in Hibiya Park. Hundreds of thousands came to pay their respects. Pallbearers selected from among the petty officers of the

Musashi

carried his casket, draped in a white cloth, past the Diet and the Imperial Palace. A navy band played Chopin's funeral march. The casket

was loaded into a hearse and driven to the Tama Cemetery, on the city's outskirts, where it was lowered into a freshly dug grave alongside that of Admiral Togo.

Yamamoto's old friends and colleagues waved away talk of establishing a “Yamamoto Shrine.” Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai recalled that the admiral had always deplored the deification of military officers. “Yamamoto hated that kind of thing,” said Yonai. “If you deified him, he'd be more embarrassed than anybody else.”

87

*

The name is a play on the term

Gato

, the abbreviated Japanese name for Guadalcanal, and

Ga

, which translates as “hunger” in certain inflections.

â

Michener's book, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1948, bears little resemblance to the better-known musical stage and screen adaptations.

Tales

was his first book, perhaps his best. He turned forty the year it was published, but somehow managed to turn out fifty more books before his death in 1997.

â¡

The ship was named not for the samurai-author, but for Musashi Province (an ancient name for a region encompassing part of Tokyo and points south).

E

XHAUSTED, BEDRAGGLED, AND BEARDED, WITH BOOTS COMING APART

at the seams and fraying dungarees hanging from gaunt limbs, the veterans of the 1st Marine Division left Guadalcanal the first week of December 1942. Many were so emaciated and disease-ridden that they lacked the strength to climb from the boats into the transports anchored off Lunga Point. Agile and well-fed sailors had to descend the cargo nets, seize them under the armpits, and haul them up and over the rails to the deck, where they lay splayed in bone-weary bliss, finally sure that they had seen the last of the odious island. At least eight in ten were suffering recurrent fits of malarial fever, barely kept in check by regular doses of Atabrine. After they were initially sent to Camp Cable, a primitive tent camp about forty miles outside Brisbane, Australia, they were transferred by sea to Melbourne, the graceful Victorian city in that nation's temperate south, where they would spend the next several months recuperating and training for their next combat assignment.

That year the War Department had published a handbook entitled

Instructions for American Servicemen in Australia

. It offered a digest of information that would be found in any civilian travel guide: statistics concerning population (“fewer people than there are in New York City”), geography (“about the same size as the United States”), natural history (“the oldest continent”), and history (largely skirting the touchy subject of the nation's origin as a penal colony). The authors took pains to emphasize the similarities between Americans and Australians. Both were pioneer peoples who spoke English, elected their own leaders, coveted personal freedom, loved sports, and had spilled blood to defeat the Axis in every theater of the war.

There were differences too, in traditions, manners, and ways of thinkingâthe handbook warned that

bahstud

was no smear, and could even be taken as a term of affectionâ“but the main point is they like us, and we like them. . . . No people on earth could have given us a better, warmer welcome, and we'll have to live up to it.”

1

That last point was evident from the moment the marines strode down the gangways onto the Melbourne docks, where they were greeted by a brass band playing the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Herded onto a train that would take them to the city center, they could hardly believe their eyes or their good fortune. The railway was lined with cheering and shouting women. They blew kisses, waved little American flags, and reached up to touch the marines' outstretched hands. Regiments were to be billeted in various suburbsâBalcombe, Mount Martha, Ballaratâbut the 1st Marines were the most fortunate because they were sent to the Melbourne Cricket Grounds, near the heart of the city, where tiers of bunks had been installed in the colossal grandstand. In that semi-protected barracks, the veterans would live out of their packs, partly exposed to wind and rain. None complained. According to Robert Leckie, they were mainly interested in a female mob that had gathered just outside the pitch. The women were “squealing, giggling, waving handkerchiefs, thrusting hands through the fence to touch us.”

2

They asked for autographs and gave their telephone numbers in return.

Discipline collapsed. Men went AWOL for days. Women reported to the officer of the day and requested “a marine to go walking with.”

3

At night, guards left their rifles leaning against the fence and disappeared into the tall grass of Victoria Park. In the entire history of the Marine Corps, a sergeant cynically observed, there had never been so many volunteers for guard duty.

A large proportion of young Australian men had shipped overseas, leaving a gender imbalance at home. War and the threat of invasion had upended conventional moral strictures and dramatized the ephemeralâlife might end tomorrow, so better live for today. Many Australian women did not mind admitting that they found the newcomers charming and alluring. Before the war, they had heard American-accented English only on the wireless or at the cinema, when it was on the lips of screen idols like Clark Gable and Gary Cooper. In person they found it exotic and magnetic. In early and mid-1942 they had feared invasion with all its horrors, and the flood of Allied servicemen gave them a longed-for sense of security.

In contrast with the Aussie “digger,” the Yank wore a finely tailored uniform and was instinctively chivalrous. He had money in his pocket and was willing to spend it. He danced outlandish jazz steps like the Jitterbug, the Charleston, or the Shim Sham. He stood when she entered a room, he held the door, he pulled out her chair, he filled her glass, he lit her cigarette, he brought flowers, and he gave gifts. She had not been brought up to expect any of that, and was not accustomed to it. The novelty was intoxicating.

Alex Haley, future author of the novel

Roots

, was a young messboy on the cargo-ammunition ship

Muzzim

. Haley had been submitting love stories to New York magazines; all had thus far been rejected. When the ship departed Brisbane in 1942, the crew enlisted his talents to compose letters to the women they had met while on liberty. Haley lifted and transposed passages from his unpublished stories. He made carbon copies so that the letters could be recycled, and even established a filing systemâeventually 300 letters filled twelve bindersâto ensure that the same woman did not receive the same letter twice. When the ship returned to Brisbane, Haley recalled, one after another of his shipmates “wobbled back” from a night at liberty on the town, “describing fabulous romantic triumphs.”

4

By no means did the Australian male lack a decent sense of etiquette. He was affable, plainspoken, and honest. There was no artifice in him, and he was ready to welcome any man as his friend. “Good on you, Yank!” was his customary hail. If an American approached him on Flinders Street and asked for an address, he did not point and give directions; he walked half a mile or more to be sure the visitor found his destination. But it was not the digger's practice to mollycoddle his woman, as if she were a princess or a porcelain doll. He drank with his mates, and not in mixed company. The Yank knew of no such constraint and saw no reason to abide by it. The moment a woman appeared, he was up out of his chair and playing at his pusillanimous and unmanly courtship routines. In the Land Down Under, a man who said “ma'am” or “please” or “after you” too bloody many times was marked as a pantywaist. Late at night, when all the girls had gone off with all the Yanks, the diggers had a good laugh among themselves at the visitors' effete and sissified ways.

James Fahey, sailor on the

Montpelier

, polled his shipmates in early 1944. Given the option to take liberty in any port in the Pacific, which would they choose? Sydney won by a commanding margin, beating Honolulu, San Francisco, and San Diego. The sentiment was universal. “It was

everyone's dream to go to Australia,” wrote a PT boat skipper in the Solomons.

5

And it would be too cynical by half to say it was just the girls. Australia was paradiseâa fairer, friendlier, more honest and open-hearted version of America. Before movies and other performances, all stood and uncovered for the “Star-Spangled Banner” as well as “God Save the King.” The climate, landscape, and wildlife were magnificent. Families opened their homes to the Americans as if they were long-lost sons. Homesick farm boys from Kansas or Arkansas took a train into the country and volunteered to work a few days in the paddocks. “When you go to Australia it is like coming home,” Fahey mused in his diary. “It is too bad our country is so far away. Our best friends are Australians and we should never let them down, we should help them every chance we get.”

6

Even in a fight, the Australian was trustworthyâhe did not pull a knife or throw a low punch. Like the Yank, he guarded his rights and was not cowed by authority. Mobs of Yanks and diggers often fought baton-swinging constables and MPs, with international alliances on either side. With the arrival of the wireless a generation earlier, Australia had felt the pull of America's cultural gravity, but now it was the Yanks who were calling one another “mate,” “bloke,” or “cobber.” First Division marines sang “Waltzing Matilda” at the top of their lungs, and added old British campaigning songs to their drunken repertoireâespecially “Bless 'Em All,” with the refrain profanely amended when no respectable citizen was in earshot. Intermarriage, discouraged by both civil and American military authority, was nonetheless relatively common. Many hundreds of Americans would settle in Melbourne and Sydney after the war.