The Dangerous Book of Heroes (25 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

The Alamo Story: From Early History to Current Conflicts

by J. Edmondson

Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions

by Thomas Lindley

The Alamo, San Antonio, Texas

Buccaneer

H

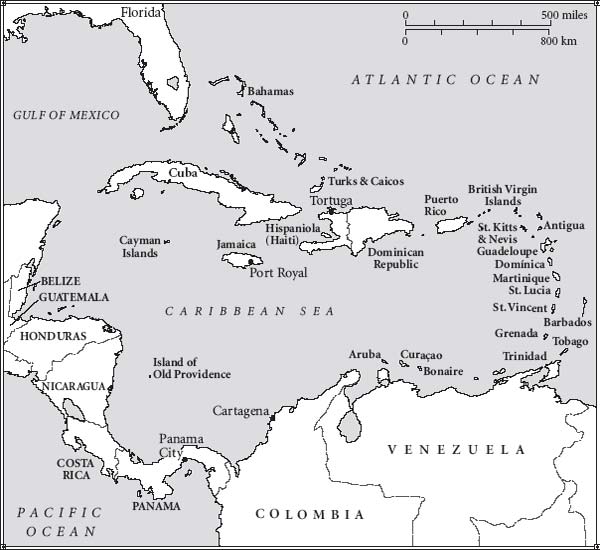

enry Morgan's life is simply an astonishing story. The history of Spanish colonies isn't taught in American or British schools, but Morgan was a pirate at a time when Britain had barely a foothold in the Caribbean Sea. Spain was the great power in those waters, with wealthy ports and cities in a vast bowl from Mexico to Venezuela and the Caribbean islands. Even today those countries have Spanish as their first language. Morgan's combination of ruthlessness, leadership, and seamanship would make him the terror of the West Indies and strike fear into Spanish settlements.

Â

He was born in Glamorganshire, Wales, in 1635. At that time, his family worked as soldiers of fortune under foreign flags and achieved high rank in Holland, Flanders, and Germany. They also fought on both sides of the English civil war. Henry Morgan's father, Thomas, took the parliamentary side and reached the rank of major general under Oliver Cromwell.

Given the turbulence of the times, it is perhaps not too surprising that few records survive of Henry Morgan's childhood. At the age of twenty, he traveled as an indentured servant to Barbados. He said later that he left school early and was “more used to the pike than the book.” It has been suggested that the young Welshman was kidnapped and sold as a white slave. In his latter, respectable days, he sued anyone who made this claim, but such events were not uncommon and the exact truth is now hidden in history. Another story is that he sailed as a junior officer on an expedition to the West Indies by Oliver Cromwell.

During the English civil war, the West Indies were the scene of battles between Cromwell's parliamentary forces and the Spaniards.

Cromwell hated the Spanish for their Catholicism and said in Parliament: “Abroad, our great enemy is the Spaniard.”

Jamaica was seized from Spain, and in the chaos and lawlessness of war, the region became infamous for pirate ships and for privateers, who were exactly the same but sailed with the approval of their governments. Tortuga, a small island off Hispaniola (modern Haiti), was a particular stronghold.

When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, the king of Spain petitioned to have Jamaica returned to Spanish rule. More than 2,500 acres of the island were producing valuable crops at that time, with huge potential for expansion and profits. Charles II refused and Parliament approved the decision. A new governor and legislative council were appointed in Jamaica, along with judges and courts. The

colony settled down and immigrants began to arrive from Barbados, Bermuda, and even America. Virgin land was offered to them, and a number of young men made their way to the West Indies, seeking to make their fortune.

It is in that context, in 1659, that Henry Morgan became captain of a privateer at the age of twenty-four. He had taken part in several raiding voyages, but instead of squandering his share of the booty, he lived simply and saved his money until he could buy a small ship of his own.

The government in England was desperate to keep hold of the threatened Caribbean ports and not too worried about who fought for them. It suited British interests to have a raiding fleet in the area, though each ship acted alone and profit was always the first motive. A report on the fledgling colony stated: “We had then about fourteen or fifteen sail of Privateers, few of which take orders but from stronger Men of War.”

From raids, slavery, and plantation crops, Jamaica quickly became a wealthy colony. From 1662 to 1688, exports doubled to more than four million pounds' worth of goods. One law passed by Parliament said that produce from all English colonies could only be transported on English ships. It meant that every colony brought a trading fleet into existence and eventually led to Britain's domination of the seas.

Thousands of miles from Europe, a smaller war was fought between Britain, Holland, and Spain for command of Caribbean waters. New men were clearly needed, and Charles II sent Henry Morgan's uncle, Edward Morgan, as senior military officer. From his years as a soldier of fortune, Edward Morgan knew the Dutch well and spoke the language. It must have been a surprise to Henry to have his uncle come out and take such a powerful position. The king made Thomas Modyford the governor and the ultimate power in Jamaica.

Modyford's first proclamation as governor was that all hostilities with Spain were to cease. In theory, all the privateers should have returned to port and been paid off. Predictably, however, they turned a blind eye to the order, Henry Morgan among them. Attacks on rich

Spanish fleets continued, and King Charles II wrote to Modyford to complain about it.

Shortly after Henry's uncle arrived, one of the privateers turned pirate, raiding English shipping as well. Under Modyford's orders, the ship was captured and the crew hanged on the docks of Port Royal in Jamaica. An example had been made, but the governor's ability to stop the privateers was limited and they carried on with their “prize taking” of foreign ships.

As the war with Holland intensified, battles took place in the East and West Indies, the Mediterranean, Africa, and North America. In England, Parliament voted £2.5 million to equip the Royal Navy for the fight. The commercial future of the world was at stake, and they were determined that Britain control the seas and trade. The privateer fleet was still terrorizing Jamaican waters, and rather than try to hunt them down, they offered them letters of marqueâofficial recognition and powers to attack Dutch ships on behalf of the British Crown. The alternative was to see them go over to the French colony on Tortuga, whereby Charles II would lose all control.

The privateer captains accepted the letters of marque, and Colonel Edward Morgan led them in an expedition to seize Dutch islands in the West Indies. A fleet of ten “reformed privateers” left Jamaica, well armed and manned. Henry Morgan was captain of one of them and already becoming known as a good man in a fight.

Colonel Edward Morgan was old and overweight. After landing on the island of Saint Eustatius, he pursued enemy soldiers on a hot day, then had a heart attack and died. His privateer captains were not the sort to return home at this setback and they went on to take the island and one other from Dutch control, gathering Spanish plunder at the same time. More than three hundred Dutch settlers were deported, but his regular soldiers had to come back to Jamaica when the privateers went off to Central America in search of more prizes.

To explain how they had managed to sack Spanish settlements as far away as Nicaragua, Captains Jackman, Henry Morgan, and John Morris claimed not to have heard that war with Spain had

ended. It was hardly necessary. Anti-Spanish feeling was still running high in official quarters, and they were in no danger of being seized as pirates.

In 1666, Modyford and his council granted Morgan and the other privateer captains new letters of marque against the Spanish. The official record gives one reason: “It is the only means to keep the buccaneers on Hispaniola, Tortuga, and Cuba from being enemies and infesting the plantations.” Modyford may not have liked the idea of employing what was effectively his own pirate fleet, but he felt he had no choice. The privateers would defend the wealth of Jamaica if they had an interest in it and a safe port there. At the same time, the French governor on Tortuga was doing his best to bribe the privateer fleet to sail for him. It was a dangerous game, with both sides trying to feed the wolves.

By then, Henry Morgan was thirty years old and well known as a successful and wealthy captain. His uncle had left a number of children in Jamaica, and Henry Morgan didn't abandon them. Far from it. The exact date is not known, but he married his first cousin Mary and spent a couple of quiet years on Jamaica, enjoying married life. Two of her sisters married officers on the council, and so the Morgan family achieved considerable influence in a very short time.

Officially sanctioned attacks on Spanish settlements and forts continued, the combination of huge wealth and poor defenses a tempting prize for fortune hunters. Privateers raided Costa Rica and Cuba as well as small islands. The Spanish attacked settlements and islands themselves, on one occasion massacring a British garrison of seventy men after they had surrendered. Some of the survivors were tortured, then sent to work in mines on the mainland. It was an unofficial war but as ruthless as any other kind. It is always tempting to take the Hollywood view of piracy as somehow romantic, with swarthy men walking the plank and crying “Yo ho ho!” to one another, but the reality was brutal and settlements that fell to privateers or pirates suffered torture and murders before being burned to the ground.

In 1667, Holland agreed to peace with England, and Spain renewed a peace that had never really happened in the Caribbean. British

power in the West Indies remained fragile, and in 1668, the Admiralty finally sent a formidable twenty-six-gun frigate, HMS

Oxford,

to the area.

Henry Morgan had been made colonel and given command of the militia in Port Royal, Jamaica. Before the

Oxford

arrived, he took a raiding expedition of ten ships to a wealthy Spanish town in Cuba. He and his men landed on March 30 and fought off an attack by Spanish militia before storming the town and stealing everything they could lay hands on. He then accepted a ransom of a thousand head of cattle in exchange for not setting the town on fire.

Other raids on Cuban towns and ports followed, often against much larger forces. However, as Morgan said: “The fewer we are, the better shares we shall have in the spoils.” It's not quite an Agincourt speech, but he and his men caused havoc on Spanish settlements, removing anything of silver and gold from cities and churches. His crews ran wild in the sacking of towns, and only the payment of large ransoms would send Morgan away. By the time he returned to Jamaica, he had a hold full of Spanish gold.

Morgan welcomed the arrival of the

Oxford

as the most powerful ship in those waters. The Spanish had warships, but they were slow and heavy in comparison. He made immediate plans for an attack on Cartagena, the strongest fortress on the coast of what is Colombia today.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Disaster struck. The

Oxford

's magazine exploded while Morgan was on deck. Five captains who had sat on one side of a table were killed in the explosion,

while Morgan and the rest were thrown clear and survived. His choice of chair had saved his life, though he lost a quarter of his men.

Without the

Oxford,

Morgan was forced to give up the idea of attacking Cartagena. Instead, he gathered the privateers off the eastern coast of Hispaniola. Fiercely independent, some preferred to sail alone, so Morgan went without them and attacked Spanish ports in Venezuela. In 1669 he sacked the city of Maracaibo and went on to the settlement of Gibraltar on Lake Maracaibo. His men tortured the city elders there until they revealed where their treasures were hidden. Morgan was not present at the time, but his name was further blackened with the Spanish as a result. The Spanish citizens of Gibraltar agreed on a ransom to Morgan's captains but could not raise all of it, so some of them were sold as slaves to make up the deficit.

It was not all raids on towns and villages. When Morgan encountered a small fleet of three Spanish warships, he and his captains captured one, sank another, and watched the crew burn the third rather than let him have it. That single raid brought more than thirty thousand pounds back to Jamaica, a vast sum for the times. In port, Morgan's men taunted the captains who had not sailed with him and flaunted their sudden riches.

With new wealth, Morgan turned his hand to owning a plantation. He leased a tract of 836 acres, still known as Morgan's Valley today, from the governor. He might have settled down, but in 1670, Spain renewed hostilities in the West Indies, capturing ships and ravaging British settlements in Bermuda and the Bahamas. In response, the governor of Jamaica appointed Morgan to command all warships in Jamaican waters. His fame, experience, and ruthlessness made him the obvious choice. At age thirty-five, Morgan was an admiral and in his prime.