The Dangerous Book of Heroes (43 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

The British Guards met the French with massed volley fire and a bayonet charge. With the Fifty-second Light Infantry, who wheeled in line to attack their broken flank, the Imperial Guards and Napoléon's last hope were smashed and broken. Famously, their bearskin hats were taken by the victorious regiments and are still worn by British Guards today. As the French soldiers ran in shock and terror, they shouted

“La Garde recule!”

âthe Guard retreats.

The Prussians attacked once more, coordinating with Wellington's own counterattack. The French army collapsed and Napoléon withdrew from the battlefield, returning to Paris where he would be forced to abdicate again and surrender. It had been his greatest gamble, and Wellington later said of Waterloo that it had indeed been a “close-run thing.”

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Napoléon was taken to the island of Saint Helena off the coast of West Africa, one of the most isolated British possessions in the world. He died there six years later, in 1821.

Â

Waterloo was Wellington's last battle, as well as his finest hour. He spent some time in Paris before finally coming home. In England he was lionized as he returned to his career in politics. He also enjoyed hunting and shooting, though he was a terrible shot and managed on different occasions to hit a dog, a gamekeeper, and an old lady as she did her washing.

Wellington represented Britain at an international congress in Verona in 1822 and took on various roles, such as Master General of the Ordnance, so was still connected to the military. He was part deafened from being too close to guns being tested, and he never recovered from the treatment, which involved a caustic solution being poured into his affected ear. He traveled to Vienna and Russia, where he met the tsar once more.

In 1828, Wellington became prime minister and held his first cabinet meeting at his home, Apsley House in London. Interestingly, he had a statue of Napoléon at the bottom of the stairs there, where it remains today. Wellington used to hang his hat on it.

He found the idea of a cabinet somewhat trying, saying, “I give them my orders and they stay to discuss them!” By then, he was close to sixty years old and had lost much of his youthful energy. Even so, he forced through a bill on Catholic emancipation, in the face of much opposition. The English people were still very wary of giving Catholics any rights whatsoever, and mobs threw stones at Wellington's home, smashing the windows. He ordered iron plates to be put in place and carried on. For this action, rather than any military success, he became known as “the Iron Duke.”

When the Earl of Winchilsea said that Wellington planned to infringe liberties and introduce “popery into every department of the state,” Wellington demanded satisfaction in a duel, which took place in March 1829. In the end, both men fired deliberately wide and the earl apologized to Wellington. At that time, dueling was illegal, and it

was an extraordinary thing for a prime minister, even one with Wellington's history, to undertake.

The bill was passed and a reluctant king gave it royal assent. Wellington went on to assist in the creation of the Metropolitan Police in 1829. The continuation of that work would fall to his successor, Robert Peel, whose policemen were known as “bobbies” or “peelers,” nicknames that endure today.

Wellington retired from political life in 1846. As Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, he spent part of his final years at Walmer Castle and died there in 1852 at the age of eighty-three. He was given a state funeral and finally interred in Saint Paul's Cathedral, where his tomb lies in the room next to that of Admiral Nelson.

Britain has since survived perhaps even darker moments and greater dangers than Napoleonic ambition, so that it is difficult to imagine the threat of foreign tyranny in those times. There is even a tendency to romanticize Napoléon in a way that Hitler has never been. Yet Napoléon wanted nothing less than the complete subjugation and destruction of British freedoms. Nelson stopped him at sea and Wellington stopped him on land. That is Wellington's enduring legacy, far more than any marble tomb in London.

Recommended

Wellington: The Iron Duke

by Richard Holmes

Saint Paul's Cathedral, London

Transatlantic, Nonstop

W

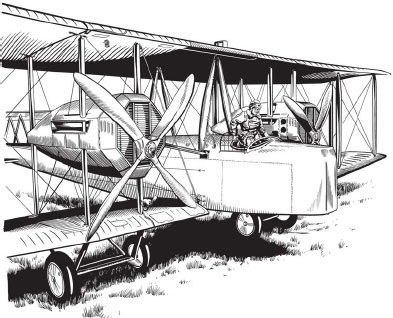

hen the First World War ended, the new world of aviation turned its attention from military to peaceful challenges. Flying an airplane in those glorious, dangerous, pioneering years meant sitting in a wooden cockpit open to the elements, with a wooden propeller in front and the wind roaring too loudly for speech. Both pilot and passenger were burned by the sun and soaked by the rain. Airplanes were called flying machines, stringbags, and birdcages, with fragile wings of wood and canvas. It was the closest thing possible to being a bird.

When the

Daily Mail

offered a prize of ten thousand pounds for the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean by an airplane, “from any point in the United States, Canada or Newfoundland to any point in Great Britain or Ireland, in 72 consecutive hours,” there was much shaking of wise heads.

The traditional first aeronautical challenge, the English Channel, had fallen as much earlier as 1785. In an Anglo-French effort by Jean-Pierre Blanchard and Dr. John Jeffries, a hydrogen balloon flew from Dover to Calais, but only by throwing all nonessentials out of the wicker basketâincluding Monsieur Blanchard's breeches. Being British and realizing that the first crossing was also the first international flight, Dr. Jeffries retained his breeches.

It was 124 years before an airplane crossed the channel. In a tiny 25-horsepower, home-built monoplane, Frenchman Louis Blériot flew from Les Baraques to Dover in 1909 to claim a

Daily Mail

prize of one thousand pounds. He very nearly crashed as he landed on the white cliffs, proving Australian flyer Charles Kingsford Smith's observation “Flying is easy. It's landing that's difficult.”

Dover to Calais is twenty-three miles, yet only ten years later the

talk was of crossing the Atlantic Ocean nonstop: 1,880 miles at its narrowest. The

Daily Mail

first offered the prize before the war as an incentive to aviation, but with the advances made in airplanesâin particular by Britain and Germanyâsuch a flight had entered the realms of the barely possible.

By April Fools' Day 1919, six contenders announced that they would attempt the crossing that year. There were five Brits and one Swede, but almost immediately Swede Hugo Sundstedt crashed his biplane during a test flight in America.

Major John Wood was the first to fly, on April 18. He took off from Eastchurch, on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent, and flew westward across Britain in a two-seater seaplane named the

Shamrock.

Slung between the floats was a massive extra fuel tank. Twenty-two miles west of Wales, his engine seized and he was forced down into the Irish Sea. He and his navigator were picked up by a passing ship. Wood's enterprise embraced the prewar spirit of aviationâadventurous, against the odds, glorious, and extremely dangerous. Disappointed, the flying major declared, “The Atlantic flight is pipped!”

The remaining four transported their planes by ship to Newfoundland to fly west to east with the prevailing winds to reach Britain or Ireland. The intrepid flyers, engineers, and riggers assembled at Saint John's, capital of Newfoundland, in early May 1919. The four teams were experienced aircraft manufacturers: Sopwith, Martinsyde, Handley-Page, and Vickers, proud names in the history of aviation.

Sopwith Aviation Company chose for its pilot Harry Hawker, a lean Australian and the company's chief test pilot. His navigator was Lieutenant Commander Kenneth “Mac” Grieve, Royal Navy. For the attempt, Sopwith chose its new biplane called Atlantic. It was powered by a single Rolls-Royce Eagle Mark VIII engine. At that time it was the most powerful air engine in the world. In the Atlantic, it produced a speed of 100 knots and a range of 3,000 nautical miles. After takeoff Hawker could ditch the Atlantic's undercarriage in the sea to give an extra 7 knots of speed. Every knot might be needed. Hawker made two 900-mile test flights of the Atlantic in Britain, and the team

was the favorite to succeed. As Hawker Company, Sopwith later produced the superb Hurricane fighter.

Martinsyde Aircraft Company also chose a small airplane. Its Raymor, a two-seater biplane, was powered by a single Rolls-Royce Falcon engine. Cruising speed was 110 knots with a range of 2,750 nautical miles, making the Raymor the fastest entrant. Its pilot was Freddie Raynham, age twenty-six. Raynham's navigator was Captain C. W. Fairfax “Fax” Morgan, a Royal Navy flyer. During the war he'd been shot down over France and used an artificial cork leg as a result. Fax was a descendant of the buccaneer Sir Henry Morgan. The Raymor was named after its pilot and navigator.

Handley-Page Transport, Ltd., then produced the largest airplane in the world, the V/1500 bomber, and selected a three-man crew for its attempt. Overall commander was fifty-five-year-old Admiral Mark Kerr with a Handley-Page pilot and navigator. The V/1500 was powered by four Rolls-Royce Eagle Mark VIIIs. The fuselage of the V/1500 was even large enough to have an enclosed cabin. Handley-Page later produced the

Victor

nuclear-strike bomber.

Vickers, Ltd., the last entrant, chose twenty-six-year-old Captain John “Jackie” Alcock, DSO, as pilot and Lieutenant

Arthur “Teddie” Brown as navigator. Alcock was born in Manchester and Brown in Glasgow. They were both ex-RAF flyers, and both had been brought down during the war. Brown had a lame left leg to remind him of his crash. He was engaged but delayed the wedding when offered the position as navigator.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Vickers chose its Vimy bomber for the Atlantic attempt, an aircraft named after the battle of Vimy Ridge. The Vimy was the second-largest aircraft in the world, 43½ feet long with a wingspan of 68 feet. A good-looking biplaneâand good-looking airplanes are usually good-flying airplanesâit was powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle Mark VIII engines. With its bomb racks and gunner's equipment removed and two extra gas tanks filled into the fuselage, the Vimy had a cruising speed of 90 knots with a range of 2,800 nautical miles. Vickers later produced the brilliant Supermarine Spitfire fighter.

The strong naval presence may seem odd now, but in 1919 the majority of air navigators were seamen. Both flyers and sailors navigate using the heavens and land features. Both use rudders, both use port and starboard, both use cockpits and cabins, and so on. The different airflows above and below a wing that “lifts” a plane into the air are exactly the same as the airflows in front and behind a sail that “draw” a vessel through the water.

The four planes had at least 1,880 nautical miles to flyâby a long, long way the greatest distance ever attemptedâyet the biggest obstacle to success was the Atlantic weather. It was unpredictable, unknown, and dangerous, with no weather ships and no weather satellites; conditions could change in moments. Gales and wind shear can blow an aircraft miles off course. Clouds and fog can blind and disorientate pilot and navigator. Ice can form on wings, destroying the lift of the machine, and in those days, instruments and engines often packed up in such extreme conditions.

In their favor was the west-to-east prevailing wind, so that even if they met contrary winds within a weather system, the system itself usually moved east. Yet even prevailing winds sometimes don't blow, and weather systems don't always follow the rules laid down by meteorologists.

“It's a piece of cake!” said Jackie Alcock after a test flight in England. “All we have to do is keep the engines going and we'll be home for tea.”

Fields long and flat enough for aircraft to take off from were rare in rugged Newfoundland. Sopwith and Martinsyde were first to arrive and found meadows suitable for their small aircraftâjust. Handley-Page located fields sixty miles from Saint John's at Harbour Grace and spent a month clearing and joining them together. Vickers took down hedges, dismantled walls, felled trees, rolled boulders, filled ditches, and even removed a stone dyke to create a five-hundred-yard airfield close to Saint John's.

Every Newfoundlander knew what was at stake, of course. Willingly, they helped the four teams prepare. Alcock christened Vickers's airfield Lester's Field, after the drayman who hauled the crated aircraft from the dockside. To ease the hard labor new words were added to a local folk song:

Â

Oh, lay hold Jackie Alcock, lay hold Teddie Brown,

Lay hold of the cordage and dig into the ground.

Lay hold of the bowline and pull all you can,

The

Vimy

will fly afore the Handley-Page can.

Â

However, it was Sopwith's Atlantic that first left Newfoundland, on the afternoon of May 18. That morning Hawker described the weather as “not yet favourable, but possible,” and began to fill his fuel tanks. Raynham made the same optimistic forecast and fueled Martinsyde's Raymor. The V/1500 was not yet assembled, while Vickers still awaited its aircraft's arrival.

At noon, Hawker and Grieve decided they'd fly and informed the other teams. In a gentleman's agreement it had been decided that each team would let the other know its plans. At 3:40 Hawker called cheerily from the cockpit: “Tell Raynham I'll greet him at Brook-lands,” and sent the Atlantic swaying across the soggy field. After three hundred yards the wheels lifted, then cleared a row of trees. The airplane was off.

Harry Hawker and Mac Grieve circled once above Martinsyde's

field alongside Lake Quidi Vidi to wave, crossed the coast, jettisoned the Atlantic's undercarriage, and headed for the British Isles. In six minutes they were out of sight in the Atlantic murk.

Two hours later, the faster Raymor, was ready and about two thousand Newfoundlanders had gathered to watch the takeoff. Freddie Raynham and Fax Morgan waved. Raynham opened the throttle and began the Raymor's run across Quidi Vidi field into a crosswind. There is less lift from a crosswind than from a headwind. After three hundred yards, the Raymor's wheels left the ground and she rose about ten feetâand obstinately stayed there, drifting slightly sideways. The Raymor dropped to the ground, the undercarriage collapsed, the propeller dug into the turf, and she crashed. Raynham was not seriously injured and crawled from the cockpit with a bang to his head, but Fax had to be lifted out and taken to the hospital. He was told he'd lose an eye.

Alcock and Brown visited Martinsyde's flyers in the hospital that evening. Raynham offered them the Quidi Vidi field so that they could assemble the Vimy for test flights while Lester's Field was completed. Meanwhile, no radio message had been received from the Atlantic. In itself this was of no concern, for 1919 was also the pioneering age of radio; they frequently stopped working.

When the Atlantic's maximum flying time of twenty-two hours was reached the next afternoon, there was still no word from Britain or any ship. It was evident that the aircraft was down somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean.

The dismantled Vimy arrived at Saint John's Harbor on May 26âthe day after good news had arrived by telegram. Hawker and Grieve had been picked up from the Atlantic Ocean by a Danish steamer and reached Scotland on the twenty-fifth. The Atlantic's radio had broken immediately after takeoff. The weather had worsened with heavy rain squalls, and after four hours the engine began to overheat. The problem was a blockage in the cooling system. By repeatedly switching off the engine, diving, then switching on again, Harry Hawker had partially cleared the blockages. They'd continued until dawn on the nineteenth, but it was clear the engine was not going to

take the aircraft to Britain. With a gale approaching, Hawker and Grieve had searched for a ship and ditched the Atlantic alongside it. Half an hour later the gale came through.

In Newfoundland, the Vimy was assembled in record time, working in the open through rain and snow. Only two weeks after arriving, the aircraft made its first test flight from the Quidi Vidi field. The same day, the V/1500 made its first test flight from Harbour Grace. On June 8 Alcock and Brown flew the Vimy in its second test flight to Lester's Field.

At Quidi Vidi, engineers and riggers were also repairing the Raymor and a navigator was found to replace Fax Morgan. Raynham was trying for another attempt. The V/1500 made her second test flight but also encountered engine-cooling problems. It was a toss-up which of the three aircraft would depart next.

Alcock drained the cooling systems of the two Vimy engines, boiled the water twice, and filtered it to remove any matter that might block circulation. He thought that the sediment in the Newfoundland water might have caused the Atlantic and V/1500 cooling problems. The weather closed in again with successive gales before clearing on the morning of the thirteenth.

Alcock made another decision at Lester's Field, possibly taking a leaf from the Atlantic's book. He removed the Vimy's nosewheel in order to reduce drag. The nosewheel was there only for landing, to stop the plane from pitching forward should the undercarriage snag in grass. The Vimy normally rested and landed on the four wheels of the main undercarriage beneath the wings and a small tail wheel. Without a nosewheel Alcock would have to ensure he made a decent three-point touchdown when he landed.