The Dangerous Book of Heroes (31 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

Howard said later: “I never saw a man with the grit that Churchill has. He simply fears nothing.”

Howard and a friend gave Churchill food and a revolver and hid him in a local mine for a time before finally smuggling him onto another train, under a tarpaulin. When Churchill saw that he had passed the frontier at last, he threw off the tarpaulin, stood up, fired his pistol, and shouted: “I'm free! I'm Winston bloody Churchill and I'm free!”

Of this part of his life, he said later: “I should not have been caught. But if I had not been caught, I could not have escaped and my imprisonment and escape provided me with materials for lectures and a book which brought me in enough money to get into Parliament in 1900.”

His second attempt to become a Conservative MP was a success, and he made his maiden speech in 1901. It was not long before he fell out with his party and “crossed the floor” of Parliament to join

the Liberals in 1904. A year later, he was appointed to government office as undersecretary for the colonies. He was promoted to the cabinet in 1908 under Prime Minister Asquith.

From the beginning, Churchill was fast on his feet in debate. He was often witty and, with his extraordinary memory, always able to answer any question with authority. In Asquith's government, he brought in laws forbidding boys under fourteen from working in mines and with David Lloyd George, then chancellor of the exchequer, created the National Insurance scheme. He was promoted again in 1910, to the Home Office, one of the most powerful positions in government. His self-confidence and energy seemed limitless. He said once that he felt “as if I could lift the whole world on my shoulders.”

In 1911, Churchill became first lord of the Admiralty and did vital work refitting an obsolete navy to answer the threat of Germany in World War I. He supported the creation of new battlecruisers and submarines as well as founding the Royal Naval Air Service. In that same year, he was involved in the famous Sidney Street siege, which involved a group of armed anarchists determined to fight to the death against police in London's East End. Policemen had already been shot and killed by the time Churchill was informed. He went to the scene and authorized the deployment of Scots Guards and

a field gun

to support the police. One bullet passed through his hat while he observed. Before the big gun arrived, the building was on fire and Churchill forbade the fire department to enter the building. The authorities waited for the gang to come out through the flames, but they stayed and died inside.

Churchill's handling of the armed gang was controversial but did little to damage his reputation as a man of action as well as politics. His calm demeanor under fire was reported across the country. After the siege, a colleague inquired: “What the hell have you been doing now, Winston?” He replied: “Now, Charlie, don't be cross. It was such fun!”

When World War I broke out in 1914, Churchill had brought the

fleet to full war footing. He did well in organizing the relief of the Falkland Islands from a German naval squadron. However, when an assault on the Dardanelles failed, Churchill was made the scapegoat and left the Admiralty. In self-imposed exile, he traveled to the trenches of Flanders and commanded the Sixth Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. In 1917 he was asked to return and became minister for munitions, then secretary of state for war and air.

After the First World War, Lloyd George was the Liberal prime minister. In 1921 he arranged to meet Sinn Féin president Eamon De Valera to discuss Irish independence from Britain. Northern Ireland wanted to remain British and later fought with the rest of the United Kingdom in World War II.

De Valera suspected the eventual deal would not reflect well on him and sent Irish Republican Army Commander Michael Collins to negotiate on his behalf. Lloyd George and Churchill, two of the most cunning and intelligent men in politics, brokered the deal. Collins was out of his depth from the beginning. The partition between northern and southern Ireland was confirmed and Ireland given dominion status. Collins had signed his own death warrant. He was later killed by Irish nationalists, while the “old fox,” De Valera, went on to be president of Ireland.

Lloyd George's coalition government collapsed in 1922, leaving Churchill without office or a seat in Parliament. Undeterred, he rejoined the Conservative Party in 1924 and became chancellor of the exchequer under Stanley Baldwin. He presented five budgets as chancellor up to 1929, when another general election brought Labour to power.

That was the beginning of a very low period in Churchill's life. Over the next decade he was almost completely alone in warning of the dangers of Hitler's Germany. His belief that Britain was unprepared for the inevitable conflict flew in the face of government opinion, and he was considered an excitable warmonger. Still, he remained at the center of power and in 1936 helped draft the abdication speech of King Edward VIII.

In 1938, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain famously returned

from meeting Hitler in Munich with the promise that he had delivered “peace in our time.” When war broke out in 1939, Churchill returned to the Admiralty and the ships at sea signaled “Winston's back.” Chamberlain resigned and Churchill formed a coalition government in May 1940 to lead Britain in the war against Nazi Germany. His first speech as prime minister would include one of his most famous statements: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.”

Bearing in mind his previous association with Ireland, it is interesting to note that during World War II, Churchill offered to give up British rule of Northern Ireland if the Irish would allow his ships and subs to use their ports. De Valera refused the offer, believing at the time that Germany would win.

The first years of the war were brutal for British forces. Churchill made his feelings clear when he said: “What is our policy? I will say: To wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give usâ¦. What is our aim? I can answer in one word: victoryâvictory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival.”

Throughout 1940, German armies seemed unstoppable. France fell incredibly quickly, prompting Churchill to comment: “The Battle of France is over. I expect the Battle of Britain is about to begin.”

Holland and Belgium fell to Hitler's invasion forces, and only by extraordinary exertions had the British Expeditionary Force been rescued from Dunkirk. Churchill uttered what may be his most famous words then: “We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.”

The battle of Britain secured air superiority in 1940, but it was almost the only moment of hope in the first disastrous years. Churchill held the nation together when all looked dark, but it was more than inspired oratory. He traveled all over the country to lift the spirits of the beleaguered people. At the same time, he was the overall com

mander of British Empire forces and took an interest in every tiny detail.

Â

In 1941, Germany invaded Russia and Japan attacked America. Churchill had his grand alliance that would defeat Hitler and the beginning of the special relationship with America that survives today.

The fighting was brutal, and British possessions Hong Kong, Singapore, and Burma were lost to the Japanese. Churchill organized massive bombing raids against Germany in retaliation for the Blitz on London. At the same time, in North Africa, he removed men from command until he found one who could bring victory against Rommel's Afrika Korps: General Montgomery.

After the vital battle of El Alamein in North Africa, Churchill said: “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

Churchill met Stalin and Roosevelt in a “Three Power” conference in 1943. The tide of the war was turning, and Allied forces entered Rome in 1944, hoisting the first U.K. flag over an enemy capital. That flag was given to Churchill and hangs from a beam at his home in Kent.

The invasion of Europe from Britain in the Normandy landings was the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany. Every foot had to be taken back by force, and the death toll for Allied armies was huge. In support, Stalin overran eastern Germany and eastern Europe, creating what would become the Soviet bloc of countries for the next forty years.

Mussolini was executed by his own people in April 1945, and Hitler committed suicide in his bunker two days later. German troops throughout Europe surrendered on May 7, 1945. The following day Churchill, acclaimed as the architect of the great victory, joined the royal family on the balcony at Buckingham Palace.

Britain had endured years of war and come close to the brink of utter annihilation as a nation. At the same time, immense social forces were at work, and after the victory the voters were desperate

for change. In the general election of 1945, Churchill's war government was thrown out and Labour came in.

Churchill took the defeat in the polls badly at first, but he was seventy-one years old and needed a rest. As well as painting, horse riding, and writing, he enjoyed building brick walls, finding the work peaceful. In the Commons, he warned of an “iron curtain” descending between the western and eastern Europe. As with Hitler's Germany, Churchill was one of the few with the vision to see the danger of a new and aggressive Soviet Union.

In 1951 the Conservative Party was returned to power. Labour had endured a tempestuous term, nationalizing industries and continuing food rationing long after the need for it had passed. As prime minister for the second time, Churchill enjoyed a rise in national prosperity. Queen Elizabeth II was crowned in 1953, and the country began to leave the dark years of the war behind.

Shortly afterward, Churchill's health deteriorated. He suffered a serious stroke and, though he recovered, decided to resign in 1955. The queen offered to make him a duke for his service, but he preferred to remain in the Commons until the end. After retirement, honors flooded in, including a Nobel Prize and honorary citizenship of the United States in 1963. He spent his final years in peace, in the south of France as well as England.

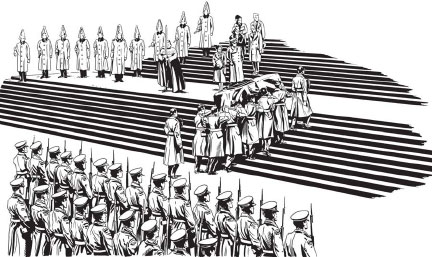

Winston Churchill died in his London home in 1965, so far from the years of his birth that it is easy to forget he was a Victorian and saw the end of the empire. At the express wish of the queen, he was accorded the honor of a lying-in-state and a state funeral, before being buried at Bladon, near Blenheim.

In all of British history, there are few lives that accomplished so much. He supported the morale of British people through the darkest years and defined the nation's spirit in his speeches and books as he crossed from the Victorian empire to the twentieth century.

I now put Churchill, with all his idiosyncrasies, his indulgences, his occasional childishness, but also his genius, his te

nacity and his persistent ability, right or wrong, successful or unsuccessful, to be larger than life, as the greatest human being ever to occupy 10 Downing Street.

âRoy Jenkins

Recommended

Winston Churchill

by C. Bechhofer Roberts

Sir Winston Churchill: A Memorial,

edited by Frederick Towers

The Wit of Winston Churchill

by Geoffrey Willans and Charles Roetter

A History of the English-Speaking Peoples

by Winston Churchill

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

The Almighty created in the Gurkha an ideal infantryman, indeed an ideal Rifleman, brave, tough, patient, adaptable, skilled in fieldcraft, intensely proud of his military record and unswerving loyalty. Add to this his honesty in word and deed, his parade perfection, and his unquenchable cheerfulness, then service with the Gurkhas is for any soldier an immense satisfaction.

âField Marshal William Slim

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

T

he father of the authors of this book flew in Bomber Command during World War II and later in the Fleet Air Arm. One of his jobs was training parachutists, and he tells a story of a group of Gurkhas, fresh to England from Nepal to begin their training. The Gurkha soldiers spoke no English, and their senior officer only understood a few words. After a final lecture, they were taken up in a plane for the first practice drop. Even at that late stage, the RAF crew weren't at all sure the soldiers had understood what was going on. One of them went back to the waiting Gurkhas and tried to explain once more.

“We are rising to an altitude of five hundred feet,” he said, “at which point, a green light will come on and you and your men will jump.” He mimed jumping.

The Gurkha officer looked worried but went back to his men to explain. When he returned, he said: “Five hundred feet is too high. We are willing to try three hundred feet.”

The RAF officer went pale. “You don't understand,” he said. “At three hundred, your parachute will barely have time to open. You'll hit the ground like a sack of potatoes.”

The Gurkha officer beamed at him and went to tell the men. They all beamed as well. They hadn't realized they would be allowed to use the parachutes at that stage of the training.

Now that story must surely seem apocryphal, but it was told at the time and it demonstrates how the British armed forces saw the regiments from Nepalâkeen, tough, uncomplaining, and unbelievably courageous. They have always been held in the highest regard, a respect they have earned time and time again in their history.

The Gurkhas have been part of the British army for almost two hundred years, beginning in 1816 when the British East India Company signed the peace treaty of Sugauli with Nepal, which allowed them to recruit local men. Gurkhas had fought them to a bloody standstill on a number of occasions, and the company was very keen to have such a martial race on its side. Lieutenant Frederick Young was one of those fighting the Gurkhas in 1815. His troops ran away, and only he refused to run as he was surrounded. The Gurkhas admired his courage and told him: “We could serve under men like you.” He is known as the father of the Brigade of Gurkhas. He later recruited three thousand of them and became the commander of a battalion, later named the Second King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles. They still serve today as part of the Royal Gurkha Rifles.

Gurkhas are small men, drawn from a rugged and inhospitable land, the sort of herdsmen who must once have formed the backbone of Genghis Khan's armies. They are famous for carrying the kukri, a curved knife that, once drawn, must be blooded before it can be sheathed.

Along with the Sikhs, Nepalese Gurkhas remained loyal to Britain during the Indian Mutiny and have fought for Britain in every major conflict since then, winning thirteen Victoria Crosses in the process. The British officers who commanded them won another thirteen. It is

part of the legend of the Gurkhas that their officers have to be as enduring and self-reliant as the men themselves, or they don't get to command.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

They have seen service in Burma, Afghanistan, the northeast and northwest frontiers of India, Malta, Cyprus, China, and Tibet. At the beginning of World War I, the king of Nepal placed the entire Nepalese army at the disposal of the British Crown. More than a hundred thousand young Nepalese men fought in France and Flanders, Mesopotamia (Iraq), Persia (Iran), Egypt, Gallipoli, Palestine, and Salonika. Twenty thousand of them were killed or injured, an almost unimaginable loss to a nation with a population of just four million. In 1915 they captured and held heights at Gallipoli, some of the worst fighting in the war. It is interesting to note that when Australian infantry battalions made a suicidal charge into Turkish and German machine-gun positions, taking them after fierce fighting, they were nicknamed “the White Gurkhas” by their allies afterward.

In World War II there were 112,000 Gurkhas in the British military, serving as rifle regiments, special forces, and parachutists. In 1940, the bleakest part of the war for Britain, permission was sought to recruit another twenty battalions to match the first twenty. The Nepalese prime minister agreed, saying: “Does a friend desert a friend in time of need? If you win, we win with you. If you lose, we lose with you.” Once again, the whole Nepalese army was placed under the disposal of the British Crown. They fought in all theaters of operation, from North Africa to Italy and finally Burma, where they repelled a massive Japanese invasion from Thailand.

As infantry, they have a reputation for incredible toughness, but it is not a historical footnote. In 2006, in Afghanistan, just forty Gurkhas held a police station against massed attacks by Taliban fighters over ten days. One of them, Rifleman Nabin Rai, was hit

in the face by a rifle bullet but refused to leave his post. When he was dazed by another round that struck his helmet, he had a cigarette to recover, then returned to his position. The Taliban attackers eventually left to seek out an easier target, leaving a hundred of their dead behind. The Gurkhas had suffered three wounds and lost no one.

Their history abounds with such examples, including the true story from 1931 of a mule kicking a Gurkha in the head with an iron-shod hoof. He wore a sticking plaster over the gash, while the mule went lame. Another tale, from World War II, involved Havildar Manbahadur being shot through the spleen, then gashed in the head by a Japanese officer. Left for dead, he walked sixty miles to catch up to his unit. Medical orderlies told him he should have died from his wounds, but he just grinned and asked to rejoin his men.

In 1943, having understood that a soldier must never lose his weapon, one Gurkha had to be rescued by Brigadier Mark Teversham after sinking to the bottom of a river. The weight of his gun was holding him underwater, but he would not let go of it. Their reputation for stoicism and macabre humor only grew in that time.

Against the Japanese, the Gurkhas earned a reputation as relentless and skilled hand-to-hand fighters. They cleared machine-gun positions by approaching under heavy fire and then leaped among the enemy, wielding their kukris' blades with terrible efficiency. The Japanese developed a grudging respect for the fearsome little men. The British commander in Burma, Field Marshal Slim, told with relish a story of a Japanese officer who challenged a Gurkha to a duel with blades alone. The Japanese officer lunged with

his sword, and the Gurkha swayed away from it, untouched. The Gurkha then stepped in close and swung his kukri.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

“You missed as well,” the officer said.

The Gurkha replied: “Wait till you sneeze and see what happens.”

In June 1944 in Burma, a Gurkha unit was faced with Japanese tanks and unable to move forward. Bhutanese rifleman Ganju Lama went on his own with an antitank gun. Although he was shot three times and his left wrist was broken, he used the gun to destroy two tanks, then stood up with bullets whipping around him and used grenades to kill the other tank crews. Only when the way was clear for his unit to move forward did he allow his terrible wounds to be dressed. He won the Victoria Cross for that action, yet it is only one story of hundreds that go some way to explain the enormous affection and respect the Gurkhas have earned for themselves.

After Indian independence in 1947, there were ten Gurkha regiments in the army of British India. Four of them transferred to the British army as a brigade: the Second King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (the Sirmoor Rifles), the Sixth Gurkha Rifles (later Queen Elizabeth's Own), the Seventh Gurkha Rifles (later the Duke of Edinburgh's Own), and the Tenth Gurkha Rifles (later Princess Mary's Own). They would play a vital role in the Malayan emergency (1948â60) and the Brunei revolt (1962â6). They also took part in the defense of Cyprus in 1974 after a Turkish invasion and as a garrison in Belize in 1978.

In the battle for the Falkland Islands in 1982, the Gurkhas were involved in the final assault to liberate Port Stanley from Argentinian troops. They were particularly feared by the Argentinian soldiers, whose own propaganda had led them to believe the Gurkhas were savages who killed their own wounded, slit Argentinian throats, and sometimes even ate the enemy.

While the Second Scots Guards took Mount Tumbledown and the Second Para took Wireless Ridge, the Gurkhas' objective was the key position of Mount William. To the north of Tumbledown, there was a minefield the Gurkhas could either go around or feel their way through.

At dawn they chose to go through. They came under artillery fire but didn't falter as fourteen were wounded.

Meanwhile, some three hundred Argentinians were retreating before the Scots Guards when they ran into an advance Gurkha patrol. They immediately turned about and surrendered to the guards.

The main force of Argentinians on Mount William then saw that they were faced by the Gurkhas. They left their positions, threw away their rifles, and bolted for Port Stanley. The Gurkhas were bitterly disappointed to take Mount William without resistance.

“They knew we were coming and they feared us,” said Lieutenant Colonel David Morgan, then commander of the Gurkha Rifles. “Of course, I think they had every ground to fear us.” The Argentinian lines of defense were broken wide open.

Gurkha regiments also served in Iraq and Afghanistan at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Despite their history, they are in every way modern riflemen, but they maintain an age-old spirit and discipline. They see courage as the greatest aim and honor in life and regard those of their number who have won the Victoria Cross as an elite group of Nepalese national heroes. Every young man who joins the regiments today cherishes the idea that he may one day be part of that small, valiant number.

Â

One problem faced by Gurkhas from World War II is that they did not qualify for a pension unless they had served a full fifteen years. Those who had fought in Malaya, Borneo, and Brunei were sent home with just a small gratuity in 1967â71 as the overall numbers were reduced. More than ten thousand of those who returned to Nepal after risking their lives for Britain are still alive today and depend on the work of charities such as the Gurkha Welfare Trust for support.

In a landmark ruling in September 2008 the British High Court ruled that Gurkha soldiers who retired before 1997 should have the right to live in Britain. That was a huge step forward for a group

that has rarely been rewarded as it deserves. Even so, after many decades of being forbidden the right or the pension to live in Britain, a large number will prefer to spend their final years in Nepal, where the continuing work of British charities is vital.

Recommended

The Gurkhas

by Byron Farwell

Supreme Courage: Heroic Stories from 150 Years of the Victoria Cross

by General Sir Peter de la Billière

Journeys Hazardous: Gurkha Clandestine Operations: Borneo 1965

by Christopher Bullock