The Dangerous Book of Heroes (35 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Nelson's body was preserved in a cask of brandy and returned to Britain. Battle-hardened, tarred, and pigtailed sailors wept when they learned of his death. One wrote home: “All the men in our ship are such soft toads, they have done nothing but Blast their Eyes and cry ever since he was killed. God bless you! Chaps that fought like the Devil sit down and cry like a wench.” Britain mourned.

On January 9, 1806, in the first state funeral for a commoner, Horatio Nelsonâin a coffin made of timber from

L'Orient

âwas placed in a tomb of black marble in the crypt of Saint Paul's Cathedral, exactly below the center of the dome. He was posthumously created earl. Memorials to Captains Duff of the

Mars

and Cooke of the

Bellerophon,

who also died at Trafalgar, are nearby. So also is the modest tomb of Admiral Collingwood. Succeeding Nelson in the Mediterranean, controlling all the seas and coasts from Gibraltar to Turkey, Collingwood literally worked himself to death only five years later in the cause of freedom.

Nelson and his “band of brothers” gave Britain command of the seas for some 140 years. The famous uniform worn by sailors of the Royal Navy, most commonwealth navies, and copied by almost every other navy in the world remembers Admiral Nelson. The three white stripes around the border of the shoulder flap record the three great victories of the Nile, Copenhagen, and Trafalgar. The black silk neck scarf echoes the mourning bands worn by the seamen who pulled the gun carriage carrying his coffin, from Whitehall steps to the Admiralty and Saint Paul's.

Â

Horatio Nelson's most enduring qualities were his humanity and care of othersâthe enemy as well as his own menâand a leadership inspired by love rather than dominance. Lord Montgomery of Alamein judged him on all counts to be “supreme among captains of war.” In the French language, a sudden decisive blow is called a “coup de Trafalgar.” At Trafalgar Day dinners, the toast is a unique silent toastâto “the Immortal Memory.”

HMS

Victory

is now preserved in Portsmouth as she fought at Trafalgar and is the honored permanent flagship of the commander in chief of the Naval Home Command. She is the oldest commissioned vessel in the world. Because of battle, decay, and rot from over 250 years, little of the original oak remains today. Yet, in All Saints' Parish Church, Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk, you can touch still the timber that was afloat off Cape Trafalgar on October 21, 1805.

Recommended

The Authentic Narrative of the Death of Lord Nelson

by William Beatty

The Life of Nelson

by Robert Southey

Nelson and His Captains

by Ludovic Kennedy

Nelson the Commander

by Geoffrey Bennett

Trafalgar Square, London

HMS

Victory,

HM Naval Dockyard, Portsmouth, Hampshire, U.K.

The Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth, Hampshire, U.K.

The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London Chatham Naval Dockyard, Chatham, Kent, U.K.

Saint Paul's Cathedral, London

Guildhall Monument, Guildhall, London

Trafalgar Cemetery, Gibraltar, U.K.

T

he order to land was given at 0630 hours.

At 0902 the first landing craft reached the shore. At 0915 the first enemy mortar rounds crashed into the marines and corpsmen struggling up the steep, soft volcanic-ash beach. In two hours the shoreline was a mass of floundering equipmentâjeeps, field guns, tanks, bulldozers, amtracks, and men, hefting their individual eighty-pound loads. The Japanese pounded them with artillery, mortar, and machine guns. It was February 19, 1945. Operation Detachment, the battle for Iwo Jima, had begun.

Â

By February 1945 in World War II, the Allied navies, armies, and air forces were in ascendency over the fascist Axis powers.

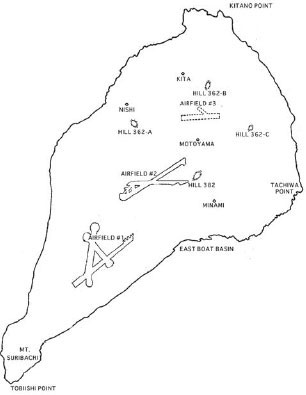

MAP OF IWO JIMA

February 19, 1945

Copyright © 2009 by Matt Haley

In western Europe, American, British, and Canadian armies gathered themselves for the final assault into Nazi Germany and Austria, and in southern Europe they were poised for complete victory. In eastern Europe the Soviet army

paused outside Dresden before its advance on Berlin. Battles had to be fought and won, but the end of six years of war was at last in sight. In the Far East, though, in the war against Japan, the situation was not so clear-cut.

In Southeast Asia, the British Fourteenth Army under General Slim was fighting steadily southward through the Burmese jungle to liberate Rangoon. In the southwest Pacific, American, Australian, and New Zealand armies under General MacArthur were advancing northward from New Guinea to liberate New Britain and the Philippines, while in the north Pacific, American and Canadian troops were advancing through the Aleutian Islands.

In the tropical central Pacific, however, the going was very tough. After the 1942 stand at Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, the U.S. Navy, Marines, and Air Force under Admiral Nimitz had island-hopped westward and northward across the Pacific Ocean. Island by island, atoll by atoll, the Pacific was liberated from Japanese occupation. Now, for the first time, American forces were to invade Japanese territoryâthe island of Iwo Jima, only 660 miles south of Tokyo. Japanese soldiers had fought fiercely before, but their resistance at Iwo Jima was to be profound. Here was some of the bitterest fighting of the entire war.

Iwo Jima lay halfway between the liberated Mariana Islands to the south and the Japanese mainland to the north. It was strategically important for several reasons. It was the next stage in the island hop to the Japanese mainland and, with Okinawa Island, formed part of the Japanese inner-defense system. This had to be punctured to reach Japan. In addition, Japan had built three airfields on the island, which were needed by the air force for its long-range P-51 Mustang fighters. From these airfields, the British-designed Mustangs would be able to protect the Boeing Superfortress bombers attacking Japan from Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. The Japanese knew the importance of holding Iwo Jima.

“Iwo Jima” means “sulphur island.” The island supplied Japanese industry with sulfur, and from its mines and caves, from fissures in the bare volcanic rock itself, sulfur gas constantly seeped into the air.

Shaped like an ice-cream cone and measuring four and a half by two and a half miles, this gray, brown, and black Pacific island is no tropical paradise. At the narrow base of the cone, the southern tip, rises the extinct conical volcano Mount Suribachi. At the broad top of the cone, the northern end, cliffs rise from the sea to a domed plateau. In 1945 there was an almost total lack of vegetation and no water. The Japanese relied upon rainwater collected in cisterns.

Defending Iwo Jima was Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, in command of almost 22,000 soldiers of the Imperial Army. Surviving documents show that Kuribayashi knew that his forces would, eventually, lose to the invading Americans. He'd been told by Japanese High Command to make the island impregnable, for once the Americans attacked, there would be no resupply or reinforcement from Japan. He had a few light tanksâunder the command of Lieutenant Colonel Baron Nishi, a gold medal winner at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Gamesâbut all his aircraft had been withdrawn for the defense of the mainland. All civilians had been evacuated.

His battle plan, therefore, was for every man to fight to the death. He wanted to cause so many American casualtiesâten enemy dead for every Japaneseâthat an Allied invasion of Japan would be too costly to consider. A negotiated surrender would thus be possible, and the sacred Japanese mainland would remain inviolate.

Kuribayashi pre-ranged and targeted the whole island from numerous concealed artillery, mortar, and rocket positions. The surface was strewn with land mines. The caves and sulfur mines were converted and strengthened into a defensive network of eight hundred concealed pillboxes, artillery emplacements, antiaircraft batteries, mortar posts, and fortified heavy machine-gun nests and rocket bunkers. They were connected by covered trenches and miles and miles of tunnels, some with underground living quarters. One complex was seventy-five feet deep, held two thousand troops, and had a dozen exits. As one marine commented, “The Japanese weren't on Iwo Jima, they were

in

Iwo Jima.”

Admiral Spruance of the Fifth Fleet commanded the American inva

sion force. He'd assembled 450 vessels, 482 landing craft, and 82,000 men in a fleet that took some thirty days sailing to reach Iwo Jima. The expeditionary troops were under overall command of Lieutenant General Smith, USMC, while Major General Harry Schmidt led the invading marines, navy corpsmen, Seabees, and Pioneers. These were a combination of experienced and newly trained servicemen.

Bombing of Iwo Jima had begun in August 1944, but from December to February it was attacked by aircraft and U.S. Navy guns for seventy-two consecutive days. In the final three days, from February 16 to 19, six battleships and five heavy cruisers bombarded Japanese positions with ten thousand shells. Although it was the heaviest naval bombardment of the war, it wasn't enough. The marines had wanted a longer bombardment, yet that wouldn't have been enough either.

The British army discovered at the 1916 battle of the Somme that the heaviest artillery bombardment is not effective against prepared and reinforced underground positions. It's not a pleasant time for the defenders, but they simply snug down until the bombardment stops. At Iwo Jima, American intelligence had also underestimated the strength of the Japanese garrison by about 70 percent. To conquer the island's eight square miles it was expected to take four days, a maximum of a week. But in this individual fight to the death all those calculations had to be discarded.

Â

In their twill uniforms, the Marine Fourth and Fifth Divisions landed on the black, volcanic southeastern beaches of Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, while the Third Division was held in reserve offshore. Operation Detachment had begun. They found that a beach of volcanic ash and dust doesn't compact under weight and pressure like a sand beach. Movement became two steps forward, one step back as the first wave of men struggled through the ash slurry to reach the initial ridge. From higher ground, Japanese machine-gun fire cut them down in swathes, the survivors pinned behind the ridge.

Below, the beach became clogged with succeeding men and

equipment, while enemy artillery, mortars, and antitank guns “walked” their shells along the numerous targets. If the marines couldn't break out soon, disaster threatened.

With considerable courage and heavy casualties, the “leather-necks” forced themselves over that initial bullet-swept ridge and fought their way through the first Japanese defenses. By the close of the day, thirty thousand men had been successfully landed, a small beachhead had been established, and some marines had actually reached the opposite western shore.

They'd suffered a total of 2,240 casualties, including 501 killed. Two Medals of Honor had already been earned. The ferocious fighting continued throughout the night, but the Japanese refused to be drawn into the open. It was a warning of the battle to come.

By the close of the second day, for a further thousand casualties, the Fifth Division had advanced south and west to isolate Mount Suribachi, while the Fourth had advanced north and west to capture the southernmost airfield. Both advances remained under twenty-four-hour Japanese artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire.

Offshore, the navy was radioed the coordinates of Japanese positions and pounded them with its heavy guns, while carrier aircraft attacked them with torpedoes, napalm, and rockets. The fleet came under attack just once, on the twenty-first, from suicide kamikaze “divine wind” aircraft from Okinawa. The aircraft carrier

Bismarck Sea

was sunk and the carrier

Saratoga

severely damaged and forced to retire to Pearl Harbor, while

Lunga Point

was damaged but remained operational.

At 550 feet high and with protected gun emplacements, Mount Suribachi in the south was like a medieval fortress. Despite heavy naval and aircraft bombing, its guns continued to wreak havoc on the landing beach and the marine advance. Somehow, Suribachi had to be taken.

On the third day, the Twenty-eighth Regiment of the Fifth Division assaulted the slopes of the heavily defended volcano. After two days of uphill fighting, marines of the Second Battalion at last reached the summit in drizzling rain. Although the mountain wasn't cleared

of the enemy, they raised a small Stars and Stripes on a length of broken water pipe. It was 1020 on the morning of February 23.

The flag was seen by the men on the landing beaches. It was seen by the Fourth Division, then fighting for the second airfield. It was seen by the men at sea. They cheered while the ships blew their sirens and horns. Although it was the day when they were expected to have already captured most of Iwo Jima, it was a seminal moment for them all. “We knew then we'd eventually take the island,” said James Johnson of the Fourth Division.

Two hours later, while still fighting Japanese snipers for total control of Suribachi, a larger eight-foot flag from a landing craft replaced the first flag. It was this second flag raising that photographer Joe Rosenthal captured in his renowned photograph, instinctively snapping his shutter as he turned around from a discussion.

As the photograph was syndicated overnight across America, the six men who raised that second flag became household names. They

were marine privates Harlon Block, Rene Gagnon, Ira Hayes, Franklin Sousley, and Michael Strank and navy corpsman medic John Bradley. The battle on Suribachi continued as Japanese soldiers fought on until killed or sealed in their caves.

Copyright © 2009 by Matt Haley

“In one cave we counted one hundred and forty-two Japs,” said Bradley. “And the flamethrowers did a fine job on top of the mountain. We tried to talk them out. They wouldn't come out, so then we used the flamethrowers as a last resort.” This tactic became common throughout the long battle to come.

“It was inhuman,” recalled another marine, but tank flamethrowers and portable throwersâshooting jets of napalmâwere the only way to defeat soldiers fighting from fortified caves, tunnels, and pillboxes. The enemy was determined to literally fight to the death.

Meanwhile, around the second airfield at the foot of the central plateau, attack after attack by the Twenty-first Regiment and tanks were beaten off by the Japanese defenders. The airfield was ringed by pillboxes, and the Japanese used to advantage their prepared positions as well as the heights overlooking the airfield.

By the twenty-fourth, Major General Schmidt realized that the Japanese defense of Iwo Jima had been vastly underestimated and called for his reserves. The fresh Third Division was sent in between the Fourth and Fifth to attack the Japanese center. On the twenty-seventh the second airfield and the overlooking hills were finally captured, but one company of the Third Division lost three successive commanders in those bloody days. Hill 362 was nicknamed “the Meat Grinder” more than two hundred marines were killed there in just three hours of fighting.

The battle for Iwo Jima had become a war of attrition. Advancing literally yard by yard, the marines would force the Japanese soldiers from one position only for them to retire to the next prepared defense, so that the whole process had to be repeated over and over again. Even scooping out foxholes was difficult: more than a foot below the surface, the volcanic ash was too hot to stand on in boots, let alone lie down in. Even tanks could only crawl at low speed across the rocky terrain.