The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland (14 page)

Read The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland Online

Authors: Jim Defede

Tags: #Canada, #History, #General

September 13

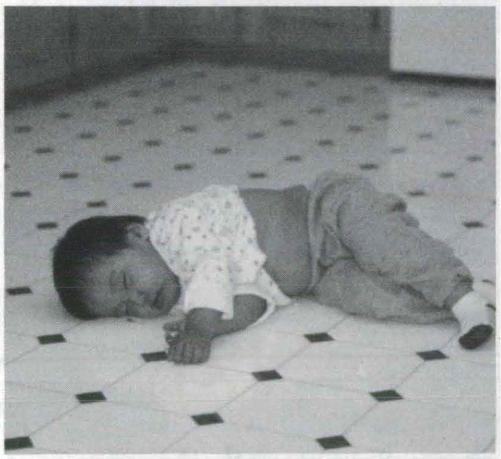

Alexandria Loper gets some rest.

Courtesy of Bruce MacLeod

B

right and early Thursday morning, Bruce and Susan MacLeod invited the Lopers and the Wakefields over to their home to use their computer and send e-mails to friends and family. The MacLeods were anxious to help in any way possible, even if it meant placing their own lives on hold for a few days. Susan’s birthday came and went on the twelfth without much fanfare because they were both volunteering at the Lions Club. And they were prepared to do the same on Monday if the passengers were still around, even though Monday was also their thirtieth wedding anniversary. There would be time enough to celebrate later, they decided.

The MacLeods “come from aways,” as the locals like to say, meaning they were from the mainland of Canada, a town called Moncton in New Brunswick. They had moved to Gander only four years before, when Bruce was transferred to Newfoundland for work. He was an air-traffic controller out at the ATC. Susan was the town’s Avon lady. Their jobs gave them the flexibility to take lots of time off and travel. Their two kids were grown and living back in New Brunswick.

Beth Wakefield couldn’t help but appreciate the MacLeods’ warmth and friendship. Walking through the house, she noticed that all of the mattresses in the guest bedrooms had been stripped. Like everyone else in the Lions Club, the MacLeods had stripped their own beds to provide sheets and blankets and pillows for the passengers.

Beth was thirty-four and her husband, Billy, a UPS driver, was forty. They lived in Goodlettsville, a small town about twenty-five minutes north of Nashville. The worst part of being stranded for both of them was being away from their son, Rob. Unlike the little girl, Diana, they’d adopted in Kazakhstan, Rob was their biological child. He was just three years old and had been expecting his parents home on Tuesday. They knew he would be upset that they weren’t there as promised.

Both the Lopers and the Wakefields were experiencing something unique. Amid all the chaos, they were trying to bond with their newly adopted daughters. In every adoption, the first days and weeks the parents spend with the child are critical. The Lopers and the Wakefields were having to spend this time living in a shelter, surrounded by strangers, and with a great deal of uncertainty hanging over their heads. Sympathizing with their predicament, the MacLeods had invited the two couples to their home for a few hours. It might not have seemed like a long time, but for the two families it was a godsend.

D

eborah Farrar had been asleep only a couple of hours when she woke to see George Neal standing over her and wearing a grin so large it should have hurt. Deb was curled up in a ball on the floor of George’s living room. She was cold and tired, and when she looked over at the clock, she saw that it was seven in the morning. George’s wife, Edna, was in the kitchen starting to get breakfast ready for her guests. And George just continued to stand over her smiling, taking his eyes off Deb only long enough to look over at Greg, who was also curled up on the floor of his living room.

“Good morning,” George said.

Deb knew she would be in for a day of teasing for having brought Greg home with her. But she didn’t care.

“George, I’m freezing,” she said. “Do you have any blankets?”

By the time Deb and Greg had arrived home from the pub in Gambo, everyone was asleep. Lana and Winnie had taken the guest room and Bill and Mark had claimed the sofas in television room, so Deb and Greg decided to sleep in the living room. As the others woke up, they all greeted Deb with a big smile and an overly friendly “good morning.”

Nothing had happened, she assured them. Greg was a perfect gentleman.

L

enny O’Driscoll bounded downstairs to find Rose Sheppard fixing breakfast in her kitchen. O’Driscoll noticed her front door was unlocked. It must have been that way through the night.

“You know, Rose, you are a very trusting person,” Lenny said.

“Why do you say that?”

“Because if I had done this in Brooklyn, I would have had my throat cut,” he said. Lenny wasn’t just referring to the unlocked front door. He was also talking about the way Rose and Doug Sheppard had invited him and his wife, Maria—two complete strangers—into their home.

Rose told him he had been living in the United States too long and needed to get back to Newfoundland more often. Lenny couldn’t have agreed more. This unexpected trip had conjured up old feelings about the country he left so long ago.

“You can’t beat a Newfie,” Lenny was fond of saying.

The O’Driscolls and the Sheppards spent all of their time together. Lenny and Doug, in particular, reminisced about Newfoundland. “When a Newfie meets a Newfie,” Lenny explained to Maria, “they have lots to talk about.”

Lenny had left Newfoundland prior to the 1949 vote to sever its economic ties to England and become a part of Canada. Doug remembered the vote well. He opposed the union, hoping instead that Newfoundland would somehow become a part of the United States. During World War II there were more than 100,000 Americans—mostly military—living in Newfoundland because of its strategic importance. At least 25,000 Newfoundland women married American servicemen back then. The island’s bond to America was always much stronger than its link to Canada.

The events of September 11 were only the most recent proof that those bonds are still there. Doug Sheppard took the O’Driscolls out to the memorial the town had built on the spot where the Arrow Air jet crashed, killing 248 members of the 101st Airborne and a crew of eight. The memorial is a larger-than-life sculpture of an unarmed soldier standing atop a massive rock, holding the hands of two small children, each bearing an olive branch.

The olive branch symbolizes the peacekeeping mission in the Sinai from which the soldiers were returning when their plane crashed. The soldier of the sculpture is looking out across Lake Gander and in the direction of Fort Campbell, Kentucky, the home base for the 101st Airborne. Behind him are three flags—the Canadian flag, the American flag, and the flag of Newfoundland. The cost of the memorial was borne by the local Masonic fraternity and its ladies auxiliary.

Also on the site is a cross surrounded by 256 trees that were planted in the field devastated by the impact of the plane. Taken together—the sculpture, the trees, the flags, and the tranquillity of lake—it is a stirring remembrance to those lost.

Designed and dedicated while Sheppard was mayor, the memorial attracts visitors year-round. For Doug Sheppard, visiting the memorial with the O’Driscolls following September 11 gave it an added meaning. And they were not alone. Hundreds of passengers stranded in Gander asked to be taken to the memorial—which is just outside of town—to see the sculpture and the plaque bearing the names of the dead and the flags now lowered to half-mast.

P

atsy Vey was on her way to work when she spotted two young women, dressed in flight-attendant uniforms, walking down the street toward the center of town.

“Would you like a ride?” Vey asked, stopping alongside the pair.

“We’re going to the shopping mall to buy some clothes,” one of the women responded.

“I’ve got clothes,” Vey quickly offered. “I’ll be glad to take you back to my house and you can take what you need.”

The women thanked her, saying it was wonderfully generous of her, but they wanted to see what they could find in the stores. On the drive to the mall, Vey had another suggestion. “If you’re bored tomorrow,” she said, “you can take my car sightseeing.”

“You want to lend us your car?”

“Why not?” Vey asked. She operates the Sears outlet in town and the car would just be sitting in a parking lot while she went to work.

“But you don’t know us.”

“You seem like nice girls,” she said. “I trust you. Besides, where would you run off to—it’s an island.”

The women demurred, saying they really couldn’t go sightseeing since they had to be ready to leave at any time. Vey told them that if they changed their minds, to come by the Sears outlet and they could take the car. Most of the time, she added, she leaves the keys in the ignition.

A

fter two days of prodding, Beulah Cooper convinced Hannah O’Rourke to leave the Royal Canadian Legion hall for a few hours to come over to her house to shower. Hannah’s husband, Dennis, promised he would stay by the phone at the legion hall, and if there was any news about their son Kevin, he would call her immediately at Cooper’s home. Normally, Cooper would bring several passengers home from the legion hall to shower. This time she brought only Hannah. Cooper could tell Hannah was exhausted. She wasn’t sleeping and the pain of having her son missing for more than forty-eight hours was taking its toll on the sixty-six-year-old woman.

While Hannah showered, Cooper, who had just turned sixty, made a fresh pot of tea. When Hannah emerged from the bathroom the two women sat in the quiet of the Coopers’ home and relaxed for a few moments. Cooper had tried talking to Hannah about her own son, who was a volunteer firefighter in Gander, to tell her she understood how a mother worries when her son is in a dangerous job. Hannah didn’t want to talk about it. She found it difficult to say much of anything about Kevin.

It was the distance that made waiting unbearable. Although Hannah wouldn’t tell Cooper, she wondered if her family on Long Island was actually telling her the truth about Kevin. Maybe rescue workers had already found him, and he was dead, but her family was afraid to tell her while she was far from home.

Before driving back to the legion hall, Cooper gave her guest a quick tour of Gander. Cooper told her about the town’s history and showed her the lake and the different sites. Every minute she kept Hannah entertained and her mind off Kevin’s being missing, Cooper considered a personal victory.

Of course Hannah never actually took her mind off Kevin, but Cooper’s persistence was endearing. Hannah was moved that the other woman would care so much to make the effort. And the time away from the legion had given her a chance to have a little privacy and collect her thoughts. She thanked Cooper for being so understanding. Returning to the legion hall, Hannah asked Dennis if there was any news. There wasn’t. They would just have to keep waiting.

O

n Thursday afternoon Tom Mercer had a few minutes to spare. He’d spent part of his day taking three teenage girls from Iran shopping at the mall and would later come to the assistance of a group of women from Mozambique, but for now he wanted to check in on his new friends Hannah and Dennis O’Rourke.

Mercer and his wife were staying with their son, an auxiliary police officer with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and their daughter-in-law, a bookkeeper at the airport. The younger couple had been called in to work during the crisis, so Mercer and Lilian, his wife of forty-four years, drove in from Port Albert to help as well. While Lilian cared for their grandchildren, Mercer enlisted in a volunteer taxi service that had sprung up to help the passengers get around town.

He was glad to help. Watching the towers collapse and the Pentagon burn had filled him with outrage. A former army sergeant, he’d spent twenty-one years in the Canadian military before retiring, and then the next twenty-two years working as an auto mechanic. He’d worked hard all his life and he couldn’t understand how someone could deliberately take the lives of so many innocent people and create such suffering for the victims’ families. Nowhere could he see the pain more clearly than on the face of Hannah O’Rourke.

Arriving at the Royal Canadian Legion hall, Mercer quickly found Hannah sitting off to the side, crying. He asked her if there was any news about her firefighter son, Kevin. He tried offering the old adage “No news is good news.”

Mercer tried talking about other matters. He sat with her and told her about the other passengers he’d met in town. There was the mother and daughter from Spain. It was because of them that he’d been at the church Wednesday night and had met Hannah and Dennis. He’d seen them several times since, and the girl had started describing Mercer as her “Newfie grandfather.” Mercer felt like he was making friends in this short period of time that would last a lifetime.

Hannah also listened as Mercer and her nephew Brendan talked about religion. Brendan was an Irish citizen who was spending more and more time in the United States. Brendan asked Mercer if there were problems in Newfoundland between Catholics and Protestants—the way there were in Ireland.

“A long time ago,” Mercer said. “Not anymore.”

“What changed?” Brendan asked.

“The young people changed things,” Mercer said. “When a young man found a young woman that he liked the look of, religion was the last thing on his mind. And if he was lucky enough to catch her, he didn’t let anything come between them.”