The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland (6 page)

Read The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland Online

Authors: Jim Defede

Tags: #Canada, #History, #General

Fast could do nothing but sit and wait along with everyone else. And since her plane was one of the last to arrive in Gander, its passengers would be among the last to be processed. The waiting gave her time to think. The day’s events filled her with shock and anger. Understandably, she wondered what was happening at the Pentagon. She worried how the attack was affecting the military’s ability to coordinate the country’s defenses against further assault. And on a personal level, she wondered how many of her friends in the building were missing or dead.

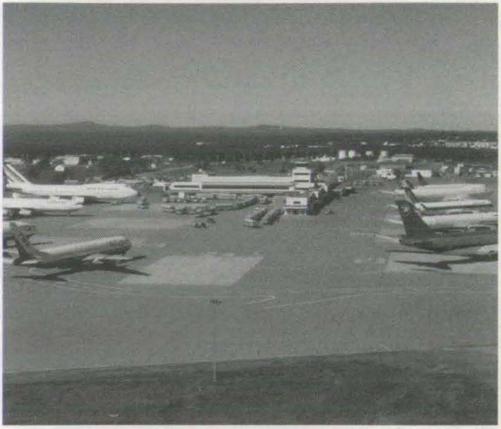

Gander International Airport, September 11, 2001.

Courtesy of 103 Search and Rescue

T

he succession of jet engines roaring over town caused people to come out of their homes and businesses to watch the line of planes in the sky. The arrival of the diverted aircraft in Gander quickly replaced the weather as the main topic of conversation. Not since World War II had the airport seen this much activity. Hundreds of people drove out to watch. Their cars clogged the access roads circling the airport as they stopped to take pictures of the different types of planes from so many different airlines. Virgin Air. British Airways. Air Italia. Air France. Sabena. Lufthansa. Aer Lingus. TWA. Delta. Continental. American. US Air. Northwest. Air Hungaria. The list went on and on.

There were military planes and a few private jets as well. There were so many planes, in fact, that airport officials had to use Gander’s second runway as a parking lot for some of them. The planes were stacked, nose to tail, one after another.

Lining the fences around the airport, people just stood by their cars waving to the passengers on board. On a few of the planes, the doors were opened for ventilation and to lessen the feeling of claustrophobia among the passengers. There were no stairs and the only way off was to jump about twenty feet to the ground, but the open doorway gave the townspeople a chance to shout hello to anyone who passed by.

Inside the airport Geoff Tucker was worrying about the logistics of having more than three dozen planes on the ground. Even if the passengers never set foot off of the planes, the aircraft were all going to need to be serviced with fuel. The toilets on the planes would have to be emptied before they started overflowing. And the planes might have to be restocked with supplies of food and water.

As Tucker started addressing these problems, in the back of his mind he believed these planes were going to be grounded for more than just a short delay since it didn’t seem likely that airspace over the United States would open up again soon. Eventually, he thought to himself, the town was going to have to find a place for all of these people.

Mayor Elliott had the same concern. There were only two groups in town that had the training and expertise to handle such a crisis: the local chapters of the Red Cross and the Salvation Army. The heads of both organizations were placed on alert.

W

hile Geoff Tucker was organizing things at Gander International Airport and Mayor Elliott was mobilizing aid organizations and members of the community in an effort to foresee the needs of the stranded passengers, an unanticipated problem arose almost immediately and needed a quick solution. Not long after the planes started landing, airport officials began receiving desperate pleas for help from many of the captains. A growing number of their passengers were climbing the cabin walls for a cigarette. Mentally these smokers had braced themselves for a six-hour transatlantic flight without any tobacco. But as their time on board the aircraft suddenly became indefinite and their stress levels skyrocketed as they tried to comprehend the severity of the situation that had brought them to Gander, the nicotine “jones” began to grip them something fierce.

A few flight crews broke the rules and allowed small groups of passengers to light up near the open door of the plane. Most, however, enforced the no-smoking mandate. On one Continental flight, two passengers needed to be sedated because they developed the shakes so bad.

The problem of how to handle these smokers was passed along to the Red Cross’s Dave Dillon. It was his idea to call Kevin O’Brien, owner of MediPlus Pharmacy.

“Kevin, I don’t know what you can do for me, but we’ve got people stuck on the aircrafts and we’ve got a problem,” he explained.

O’Brien isn’t a smoker, but he certainly could sympathize with the plight of those who were. He grabbed several empty boxes and cleaned out his entire supply of nicotine gum. He then filled the backseat of his car with twenty-five cartons of nicotine patches. In the United States a person needs a prescription before he can obtain the nicotine patch, but in Canada they are sold over the counter. O’Brien raced down to the airport, where Mounties delivered the items to each of the planes requesting them.

G

eoff Tucker had a new problem that was beginning to scare him. After all of the planes landed, tower officials made the rounds by radio, talking to each of the pilots to let them know what was happening. Five of the airplanes, however, weren’t responding to hails on their radio. The tower had alerted Tucker and he had a bad feeling. What if these five pilots weren’t responding because something awful was happening on their planes? The RCMP and the military had so effectively drummed into his head the possibility that there were terrorists aboard these planes that Tucker started to think it was true.

Complicating matters further, the tower couldn’t determine which five of the thirty-eight planes on the ground were the ones not responding. They knew the airlines and flight numbers, but they didn’t have the corresponding tail numbers. The airport’s command post is a large room with a horseshoeshaped table. Each of the major agencies has a spot at the table. Talking to the controllers in the tower and duty managers on the tarmac, Tucker could tell that both the RCMP chief and the air-force base commander were following his conversation with interest.

Tucker also realized that because the parked planes were all bunched together, an explosion on one of the planes would probably destroy all of the ones around it as well, in a virtual chain reaction. Not wanting to sound alarmist, Tucker suggested that his ground crews might want to try to find those missing planes as soon as possible.

B

y mid-afternoon it was obvious that U.S. airspace was going to remain closed for the foreseeable future. When the word officially arrived from the FAA, town leaders were already establishing shelters for as many as 12,000 people. The schools were the most obvious place to start.

Terry Andrews received the call just before classes were to be let out for the day at St. Paul’s Intermediate, the town’s junior high school. As the principal, he went on the PA system and instructed all of the students to clean out their desks, since they were going to have to fill up the classrooms with cots. Similar messages were being delivered at the high school, Gander Collegiate, and the elementary school, Gander Academy.

All of the churches in town were placed on notice, as well as the fraternal organizations such as the Lions Club, the Knights of Columbus, and the Royal Canadian Legion hall.

Without waiting to be asked, the mayors from the smaller surrounding towns started calling in, offering their own facilities for passengers. The Salvation Army not only had churches in several of these towns, but they also had a summer camp, out in the woods, which could hold hundreds of people.

The air force base, 9 Gander Wing, was already on alert. All of its airmen and reserves were called in and the officers’ club was quickly converted into a shelter.

One place where passengers wouldn’t stay was in any of the town’s 550 hotel rooms. Soon after the planes landed, Geoff Tucker realized he needed to make sure the flight crews had a decent place to stay. Pilots and flight attendants are required to have a certain amount of rest or they are not allowed to fly. Tucker estimated there to be 500 pilots, copilots, flight engineers, pursers, and flight attendants aboard the planes. Tucker called town manager Jake Turner.

“We’re going to need every hotel room in town,” the airport vice-president told him. “You are going to have to seize all of the rooms and force the hotels to cancel any existing reservations they have.”

“I can’t do that unless the town council declares a state of emergency,” Turner replied.

“Well, then, I guess you need to declare a state of emergency,” Tucker said. He explained the situation to Turner. Within two hours the town council met and declared that a state of emergency was now in effect. Tucker’s instincts were right. A number of quick-thinking passengers had already used their cell phones to call local hotels and book blocks of rooms with their credit cards. Once the state of emergency was declared, all of those reservations were canceled.

Tucker soon discovered another crisis that had been averted. After visiting each of the planes personally, his ground managers reported that all of the planes had been accounted for, including the five planes that failed to respond to radio hails earlier. Some of the pilots had either shut down their radios to conserve power or were monitoring a different frequency when the tower called. Tucker let out a sigh of relief when he heard the news. Finally, he thought to himself, things were starting to look up.

M

oving the passengers off the plane was going to be complicated. The first issue was security. In order to ensure everyone’s safety, officials would deal with only one plane at a time, in the order in which they landed. After getting off the plane, the passengers would run through a gauntlet of security. They would go through metal detectors as well as being patted down. Then their carry-on bags would be emptied and searched. All of the luggage they checked onto the plane before departing would stay in the belly of the plane.

After clearing security, they would proceed through customs and immigration. This was complicated by the fact that only one immigration agent had been assigned to Gander, Murray Osmond. Help was on the way from St. John’s, but in the beginning at least, Osmond was on his own.

From there the passengers were turned over to the Canadian Red Cross and Des Dillon. A retired government employee, Dillon had been involved with the relief agency for thirty years and was specially trained as a disaster coordinator. In 1994, he was sent to Los Angeles following the devastating Northridge earthquake, which killed fifty-seven people. He supervised more than two thousand volunteers during that catastrophe. He had also helped coordinate relief efforts after the 1998 Swiss Air crash off the coast of Nova Scotia. The Red Cross would register each and every passenger and keep track of which shelter they were assigned to. Within a couple of hours Dillon had two hundred volunteers at the airport. He wanted to move the passengers through the airport as fast as possible so that those on the next plane could be taken off. He made sure all of the television sets in the airport were either hidden or unplugged. He knew the passengers hadn’t seen any of the images of the attack and was afraid they would emotionally break down in the terminal. To keep them moving, Out of Order signs were posted on all of the pay phones in the airport. The phones actually worked, but officials were afraid people would stop and wait in line to call their homes.

The biggest problem facing officials was transportation. How do you move almost 7,000 people to shelters, some of which were almost fifty miles outside of town? The logical answer was to use school buses. On September 11, however, Gander was in the midst of a nasty strike by the area’s school-bus drivers.

Amazingly, as soon as the drivers realized what was happening, they laid down their picket signs, setting their own interests aside, and volunteered en masse to work around the clock carrying the passengers wherever they needed to go.

In town, the Salvation Army was in charge of gathering supplies and acting as a central clearinghouse for the shelters. The local radio station and public-access television station started running announcements asking folks in town to donate food, spare bedding, old clothes—anything the passengers might need. At the town’s community center, a line of cars stretched from the front door for two miles as people brought sheets and blankets and pillows from their homes for the passengers.

Local stores donated thousands of dollars’ worth of items. O’Brien, the pharmacist, coordinated with all of the other pharmacies in the area to supply all of the toiletries the unexpected arrivals might need, including a special shipment of 4,000 toothbrushes.

O

nce all 252 of the planes diverted to Canada were safely on the ground and it was clear that none of them would be taking off again, Dwayne Puddister left Gander’s air-traffic control center, picked up a steak and some beer, and headed over to the home of fellow controller Keith Mills. Soon a half-dozen other controllers from the center arrived for a celebratory barbecue.

None of them had ever been through a day like this. They were all so relieved it was over that none of them wanted to be alone. The closest thing Puddister could liken it to was driving on icy roads through a blinding snowstorm; both hands on the steering wheel, knuckles white, and hypersensitive to everything, you don’t realize how scared you are until you pull into the driveway. In the morning, Puddister would help unload supply trucks at one of the local community centers that had taken in passengers. Tonight, however, he’d have a thick steak and a few bottles of Canadian ale.