The Devil Soldier

Authors: Caleb Carr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Asia, #Travel, #Military, #China, #General

Copyright © 1992 by Caleb Carr

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. This work was originally published in hardcover by Random House, Inc., in 1991.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Carr, Caleb

The devil soldier: the American soldier of fortune who became a god

in China/Caleb Carr.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76552-9

1. Ward, Frederick Townsend, 1831-1862. 2. China—History—

Taiping Rebellion, 1850-1864—Personal narratives, American.

I. Title.

DS759.35.W37C37 1995

951′.034′092—dc20 94-45844

[B]

v3.1

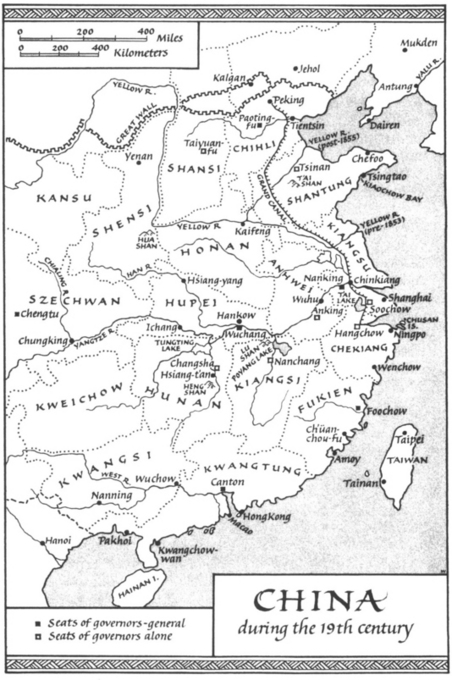

A NOTE ON NAMES

Because of the vast array of spellings used in the translation of Chinese during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, all place and personal names in the following text have been adjusted to a uniform system, regardless of their source. A slightly older style of translation than the current Pinyin has been used, because it is easier for English-speaking readers to pronounce. This explains why

Beijing

is still

Peking

and why American, Chinese, British, and French speakers and writers appear to be using the same spellings, when in fact they employed many different versions.

—C.C.

CONTENTS

Prologue:

“Across the Sea to Fight for China”

VI:

“His Heart Is Hard to Fathom”

VII:

“Accustomed to the Enemy’s Fire”

PROLOGUE

“ACROSS THE SEA TO

FIGHT FOR CHINA”

In the summer of 1900 an expeditionary force of European, Japanese, and

American soldiers marched into the Chinese capital of Peking, the triumphant blare of their bands and bugles announcing not only the conclusion of a successful campaign but the effective end of thousands of years of imperial rule in China. The last of the Middle Kingdom’s dynasties, the Manchu (or Ch’ing), had withstood internal and external threats throughout the nineteenth century, and would hold on for eleven more years before a tide of republican revolution would engulf it completely. But all hope of recovery was in fact lost when the Western and Japanese troops entered Peking and its sacrosanct Forbidden City, the inner compound guarded by high walls that for centuries had been the residence of China’s rulers. The violation of the Forbidden City by “barbarian” foreigners stripped the Manchus of any legitimate right to rule in the eyes of many Chinese, and the imperial clique was finally seen for what it was: an arrogant, corrupt group of anachronisms, whose sumptuous world of silk dragons, peacock’s feathers, and divine rule had no place in the twentieth century.

The Western and Japanese governments had ordered the march on Peking because a group of antiforeign Chinese extremists known as the Boxers, under orders from the Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi, had laid siege to their diplomatic legations and attempted to kill their ministers. The attack on the legations was a stupendously rash act, the crowning achievement of an imperial elite that had spent the last half century

trying to stem the advance of foreign influence in China and preserve the empire in its near-medieval state. All such efforts had been in vain: The barbarian outsiders had finally pried China open to foreign trade, foreign religion, and foreign political ideas. The bitter Tz’u-hsi had meant to make the “foreign devils” pay for their success when she authorized the attack on the legations in June 1900. But the Western diplomats and their families had once again frustrated her by bravely withstanding the siege. When the multinational relief column marched into Peking in July, Tz’u-hsi fled in disgrace, taking with her the last chance of imperial resurgence. In the conflict between unreasoning Chinese pride and relentless foreign commercial and philosophical expansionism that had raged for sixty years, there seemed to be no middle ground, and now Chinese pride had lost the long battle.

Yet there had once been such a middle ground in the Middle Kingdom, or at least the possibility of it. For the briefest of moments during the 1860s, the imperial government in Peking as well as the foreign powers had gotten a glimpse of a China in which progressive Western ideas—particularly military ideas—would be placed at the service of the emperor and his ministers to ensure the empire’s survival and participation in a rapidly changing world. Unfortunately, both the Chinese imperialists and the Westerners, as if horrified by their glimpse of this strange future, had slammed the door on it; but not before the names of those who had so briefly cracked the portal open had been recorded and honored by the Chinese people. Legends quickly grew around those names, as at least one group of American soldiers discovered during their occupation of Peking in the summer of 1900. Writing a quarter of a century later, one of these men recalled,

There was much talk among the soldiers as to who had been the first to enter the Forbidden City, where no white “devil” was ever supposed to have been before. One day a group of us were arguing about the matter before a little Chinese shop, where we had stopped for one thing or another, and of a sudden the old merchant spoke up, in pidgeon English.

What did it matter, he wanted to know, which one of us had by force of arms broken into the temples of the gods? We were disrespectful of the gods, we were like burglars, for all our bravery. And we could never be the first white men to enter a sacred Chinese temple, anyway, because there was Hua, the White God. Hua had been braver than any of us—and he had been good, too. He had come from far across the sea to fight for China, and he had been carried into a sacred temple, and was there still. His was a victory of right.

The “Hua” of whom the old Chinese merchant spoke was Frederick Townsend Ward, a young soldier of fortune from Salem, Massachusetts, who had come to China in 1859 and offered his services to the imperial government in its bitter war against a hugely powerful group of quasi-Christian mystics calling themselves the Taipings. When he arrived in Shanghai, Ward was twenty-eight years old and penniless; when he died in battle three years later, he was the most honored American in Chinese history, a naturalized Chinese subject and a mandarin entitled to wear the prestigious peacock feather in his cap. He had married the daughter of another mandarin and received high praise from the emperor. But above all, he had assembled out of the most improbable elements an army that was unlike anything China or the world had ever seen: a highly disciplined force of native Chinese soldiers commanded by Western officers that was expert in the use of modern foreign weapons and capable of defeating vastly superior numbers of opponents in the field. Known to the Taiping rebels as “devil soldiers,” Ward’s men were dubbed the

Chang-sheng-chün

, the “Ever Victorious Army,” by Peking; and after Ward died a memorial temple and Confucian shrine were built around his grave.

More than any other person or organization, Ward and his Ever Victorious Army had pointed the way toward a different kind of China, one in which Manchu chauvinism would have given way to reasoned Chinese acceptance of outside assistance. That assistance would in turn have allowed the empire to avoid a violent collision with progress and emerge as a twentieth-century power. China’s failure to follow such a course had, certainly, less to do with Ward’s untimely death than with the fact that the Manchus did not truly desire progress and the West

did not desire China to be a power. But the momentary achievement itself, the transitory indication that an alternate future was possible, was nonetheless important—was, in a very real sense, Ward’s greatest victory.

What follows is not a biography of Frederick Townsend Ward in the conventional sense, for it would be impossible to write a conventional biography of a man whose legacy has suffered so many attempts at eradication. Ward’s service to the Chinese empire gave him great renown in the distant, troubled country that he adopted as his own. His memory was honored and his eternal spirit appeased (or so it was hoped) with annual sacrifices at the shrine built to his memory. But the ever-suspicious imperial Chinese government harbored lingering anxiety concerning Ward, largely because of his foreign origins. In the United States, by contrast, Ward’s exploits received only passing mention in Congress and the press following his death, and then were virtually forgotten. For their part, the Ward family made repeated attempts to pry money owed to their illustrious relation out of the Chinese government, but they did little to ensure that an accurate account of his life would endure.

When the imperial Chinese government finally collapsed in 1911, Ward’s legacy was further endangered. The American Legion named its Shanghai post after him and tried to maintain his grave during the era of Republican China. But China’s new rulers were not sympathetic, for Ward—although his origins were American and he harbored doubts about the shortcomings of the Manchu dynasty even after he became a Chinese subject—had fought for the Manchu cause. His private misgivings about imperial corruption and repression were considered academic by most of the Republicans. Then, too, Sun Yat-sen had fallaciously but effectively traced the origins of Chinese nationalism back to the Taiping rebellion, which Ward had helped defeat. It thus comes as no surprise that Sun and his followers did little to perpetuate Ward’s memory.