The Dictionary of Homophobia (111 page)

The political affirmations of contemporary gay and lesbian movements have troubled collective opinions and self-imaging by claiming to put a name and “identity” on age-old practices that were historically tolerated as long as they remained clandestine and secondary. In a rather classic paradox, this “negative freedom,”

which allowed one to be and do whatever one wished under the shelter of secret practices and love without a name, found itself threatened by “liberation,” leading to phases of collective tension; a response, in the first instance, to the assertion of identity. Using the example of the army, Bersani notes that “the inherent homoeroticism of military life certainly risks being revealed to those would want to both deny it and continue to take advantage of it, if active homosexuals publicly proclaim their preference.” More radically, it is the entirety of “homo-social” relations that homosexual affirmation threatens to “desublimate” by revealing the homosexual eroticism within these relations, often are tacitly exploited in everyday interactions (consider, for example, the sublimated sexual tension that in the “frank and virile camaraderie” of men).

Finally, just as spelling mistakes, if they are too numerous, threaten to drastically change spelling (unlike an error in counting, which, in itself, has no consequence for mathematical truth), homosexuality threatens, if it is too radically emancipated, to “deinstitutionalize” heterosexuality. That is to say, to rob it of its socially dominant status. The “peril,” therefore, is not simply in the minds of homophobes, but in the reality of a political relation that is under construction. It does not concern “society,” but rather a certain structure of oppression. If the “spontaneous” impression that there are “more and more” homosexuals corresponds to an optical illusion repeated from generation to generation, this illusion depends on a rather well-founded awareness of the risks such a “spontaneous generation” poses to heterosexual privileges. Thus, we could conclude by saying that after further examination of the social logic at work, there is no possible doubt: gays and lesbians are, in fact, dangerous.

—

Sébastien Chauvin

Bersani, Leo.

Homos

. Paris: Odile Jacob, 1998. [Published in the US as

Homos

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1995.]

Borrillo, Daniel. “Que sais-je?”

L’Homophobie.

Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 2001.

Bryant, Anita.

The Anita Bryant Story: The Survival of Our Nation’s Families and the Threat of Militant Homosexuality

. Old Tappan, NJ: Revell, 1977.

Bull, Chris and John Gallagher.

Perfect Enemies: The Religious Right, the Gay Movement, and the Politics of the 1990s

. New York: Crown Publishers, 1996.

Fortin, Jacques.

Homosexualités: l’adieu aux normes

. Paris: Textuel, 2000.

Herman, Didi.

The Antigay Agenda

. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1997.

Hirschman, Albert O.

Deux Siècles de rhétorique réactionnaire

. Paris: Fayard, 1991.

Hocquenghem, Guy.

Homosexual Desire

. New ed. Paris: Fayard, 2000. First published in 1972.

—Abnormal; Communitarianism; Contagion; Debauchery; Heterosexism; Otherness; Proselytism; Rhetoric; Sodom and Gomorrah; Sterility; Symbolic Order; Theology.

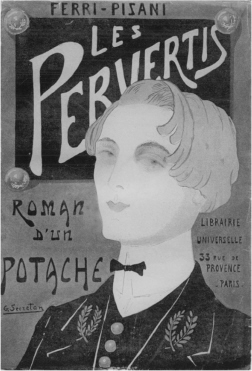

PERVERSIONS

“Sexual perversion” was the generic term used in psychiatry during the second half of the nineteenth century to describe all sexual practices and attractions that did not lead to reproduction. The work of German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing to classify “perversions” is at the center of this definition. In his study

Psychopathia Sexualis

, he determined a typology of four different categories of sexual deviance, defined by flawed sexual desire (e.g., homosexuality, bestiality, fetishism), behavioral anomaly of the sexual instinct (e.g., sadism, masochism), diversion of other physical functions to a sexual end (e.g., urophilia, scatophilia), or finally, the limiting of sexual behavior to practices perceived as “preliminary” (e.g., voyeurism,

exhibitionism

).

Starting at the end of the nineteenth century, the theme of sexual perversion was frequently found in literature dealing with homosexuality.

However, despite the enormous list of perversions identified by Krafft-Ebing, homosexuality served as the theoretical model upon which he constructed the base of his scientific theory, and which furthermore was most often associated with other perversions in his clinical descriptions (e.g., homosexuality and sadism, homosexuality and fetishism, etc.). In this manner, homosexuality is depicted as the “mother” of all perversions and, as such, it is not surprising that the terms “homosexual” and “pervert” became almost synonymous among homophobes.

Without reverting to the concept of perversion in analytical theory—which, after the works of Freud, have very little to do with the psychiatric concepts of the nineteenth century—“sexual perversions,” as understood by Krafft-Ebing, were an important part of the vocabulary of contemporary sexology, but were also pornographic, thus reinforcing the enduring negative representations of homosexuality as “perverse.”

—Pierre-Olivier de Busscher

Charcot, Jean-Martin, and Valentin Magnan.

Inversion du sens génital et autres perversions sexuelles

[1883]. Paris: Frénésie Editions, 1987.

Danet, Jean. “Discours juridique et perversions sexuelles (XIXe et XXe s.).”

Famille et politique

. Vol. 6. Center for Political Research, University of Nantes. Faculty of Law and Political Science, 1977.

Krafft-Ebing, Richard von.

Psychopathia Sexualis: Etude médico-légale à l’usage des médecins et des juristes

. Paris: Payot. 1950. [Published in English as

Psychopathia Sexualis

.]

Lanteri-Laura, Georges.

Lectures des perversions: histoire de leur appropriation médicale

. Paris: Masson, 1979.

—Biology; Degeneracy; Fascism; Endocrinology; Ex-Gay; Genetics; Himmler, Heinrich; Hirschfeld, Magnus; Inversion; Medicine; Medicine, Legal; Pedophilia; Psychiatry; Psychoanalysis; Treatment; Vice.

PETAIN, Philippe

There is no doubting the homophobia of Philippe Pétain (1856–1951), the French general who eventually became the Chief of State of Vichy France from 1940 to 1944 following the military defeat of France by Nazi Germany during World War II. His homophobia is not surprising for a man of his generation, given his origins and experiences: he had a rural Catholic childhood, and his family included extremely pious grandparents as well as two uncles who were clergymen. He studied at the “free” college in St-Omer, but overall he led a rather stern life, and maintained ties to the Church and the conservative right from his youth until his death. Moreover, Pétain was known for his numerous affairs (married late in life in 1920, he had many young girls and married women as lovers until the 1940s). Without a doubt, heterosexuality was for him self-evident, and he was often boorish in his homophobia. On one occasion in 1916, Pétain refused to have the writer Pierre Loti at his table because “that little pretentious and painted old man” had eye makeup and wore rouge. He even wrote to the French Minister of Marine that Loti, who was a naval attaché at the time, “would probably be more useful in Morocco with [Hubert] Lyautey,” a French general who was Resident-General of Morocco at the time, a perfidious allusion to the latter’s morals. Pétain’s prejudices poisoned his relationship with Lyautey in 1925– 26, when Pétain himself was sent to Morocco to put down a rebellion led by Abdel-Krim. During the Nazi occupation, his homophobic attitude came to light again when he and his wife nicknamed Abel Bonnard, one of the Ministers of Education in the Vichy regime, “

Gestapette

” (Gestapo-fag).

Pétain’s homophobia, which probably was not that much different from millions of French of his generation, became very clearly political beginning in June 1940, when he signed an armistice with Nazi Germany giving them control over the north and west areas of the country, including Paris and the entire Atlantic coastline, but leaving the remaining two-fifths unoccupied, which became Vichy France. Homophobia was at the heart of Vichyist criticism of moral liberalism and hedonistic individualism stemming from the French Revolution, resulting in a lowered birthrate and moral

decadence

. The relative visibility of homosexuality during the 1920s and 30s was, according to the Vichy right, the very incarnation of the moral decay that had pervaded the French Third Republic (1870–1940); the fact that there were known homosexuals in the entourage of French Prime Minister (until 1940) Edouard Daladier, in particular his Chief of Staff Edouard Pfeiffer (apparently a sadomasochist), was no doubt fuel for the fire. The mortal sin of the Third Republic was that the “spirit of enjoyment had won over the spirit of sacrifice”; Pétain clearly felt this way, telling writer Henri Bordeaux in July 1943 that he had been beaten by “every pleasure seeker and every advocate of the Third Republic.” It appears that, as far as Pétain was concerned, homosexuality, in its search for a pleasure that is disconnected from the

family

as well as from society is a form of that abominable individualism, “which is exactly that from which we almost died.” (In light of his stern pronouncements, it is rather amusing to note that Pétain’s sexuality, as heterosexual as it was, was never focused on procreation: he had a multitude of affairs but never fathered any children.) Everyone in the marshal’s entourage (Raphaël Alibert, Dr Ménétrel, the admirals) were united in their reactionary, conformist (steak-and-cigar, white-collar oafs), and strongly Catholic homophobia (which is very similar to the type of homophobia exhibited decades later by French politicians Philippe de Villiers, Charles Millon, and Christine

Boutin

). The concern for setting the right tone often prevented the explicit mention of homosexuality, but it was no less implicit in all the great texts of Vichyist ideology. In fact, it was a popular target in the majority of Vichy arguments on youth and

literature

: French writer René Gillouin, a friend and supporter of Pétain who, even before World War II, denounced the morals of

Gide

, Cocteau, and Parisian literary circles, saw in homosexuality the cause of the end of the Third Republic in 1940; according to him, the sinister influences of homosexuality caused the French to become “a people ravaged by alcoholism, rotted by eroticism, [and] eaten away by a falling birthrate.” Writer René Benjamin, a pamphlet-waving admirer of Charles Maurras (head of the monarchist, counter-revoluntionary movement Action Française), chose to combat “art that believes that the purest of the pure is to reveal that which the moral

police

still hides temporarily.” Moreover, the Vichy regime’s family- and pro-birth-oriented arguments were, in the cultural context of the time, implicitly homophobic: united in its conservative viewpoint, the Vichy exalted the “eternal feminine,” the complementary nature of the sexes (in a perfectly misogynist way), and the patriarchal structures that were so dear to French philosopher Gustave Thibon.

Despite its homophobia, Vichy did not deport homosexuals from France; the only homosexuals to be deported were the Alsatians from Moselle, according to the instructions of the German penal code between 1940 and 1944. However, Vichy homophobia still had disastrous consequences for French homosexuals because in 1942, Pétain set the stage for the return of legal

discrimination

. In fact, the law of August 6, 1942, for the first time since 1791, specifically criminalized homosexual relations: it created a new article in the penal code, Article 334, which specified imprisonment of those who committed same-sex “acts that were shameless and

unnatural

” with a minor under the age of twenty-one years. The worst part, however, was the fact that the anti-gay article was maintained under President Charles de Gaulle after France was liberated after the war: the order of July 27, 1945 redefined it as Article 331, paragraph 2 of the penal code, which remained in effect until 1982. In more recent years in France, the very slow “de-Pétainization” of the country must be taken with a grain of salt: the Christian Democrats and the Communist Party, both of which emerged from World War II stronger, were just as homophobic as was Vichy; and in its views toward society, Gaulist thought is very similar to Pétainism (it is doubtlessly what motivated Pétain in July 1944 to state: “Fundamentally, we have the same ideas”). We must also remember that many Gaulists, Communists, and resistant Catholics contributed to the belief that Nazism was a homosexual movement and helped to hide the persecutions of the “pink triangles” during the war, thereby increasing the symbolic stigmatization of homosexuality. It is clear that, as far as gays and lesbians were concerned, 1944 did not bring about any real form of liberation.

—Pierre Albertini

Borrillo, Daniel, ed.

Homosexualités et droit

. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1998.

Griffiths, Richard.

Pétain et les Français, 1914-1951

. Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1974. [Published in the UK as

Marshal Pétain

. London: Constable, 1970.]