The Dictionary of Homophobia (13 page)

Boswell, John.

Christianisme, tolérance sociale et homosexualité

. Paris: Gallimard, 1985. [Published in the US as

Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century

. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1980.]

Damien, Peter.

Liber Gomorrhianus, Patrologia, Series Latina

[ed. Migne]. Paris: Garnier Frères, 1844. Translated by Pierre J. Payer in

Book of Gomorrah

. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, 1982.

Jordan, Mark.

The Invention of Sodomy in Christian Theology

. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1997.

Halperin, David.

Cent ans d’homosexualité (et autres essais sur l’amour grec)

. Paris: EPEL, 2000. [Published in the US as

One Hundred Years of Homosexuality: And Other Essays on Greek Love

. New York: Routledge, 1990.]

Lacoste, Jean-Yves, ed.

Dictionnaire critique de théologie

. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1998. [Published in the US as

Encyclopedia of Christian Theology

. New York: Routledge, 2005.]

Leroy-Forgeot, Flora. “Nature et contre nature en matière d’homoparentalité.” In

Homoparentalité, états des lieux

. APGL symposium. Paris: ESF, 2000.

McNeill, John.

L’Eglise et l’homosexuel, un plaidoyer

. Geneva: Labor & Fides, 1982. [Published in the US as

The Church and the Homosexual

. Kansas City: Sheed Andrews and McMeel, 1976. Fourth edition: Boston: Beacon Press, 1993.]

Thévenot, Xavier.

Homosexualités masculines et morale chrétienne

. Paris: Le Cerf, 1985.

—Bible, the; Biology; Damien, Peter; Debauchery; Decadence; Degeneracy; Heresy; Judaism; Medicine; Paul; Sterility; Theology; Vice.

ANCIENT GREECE.

See Greece, Ancient

AIDS

It has become commonly accepted that sympathy for the gay community as a result of the AIDS epidemic contributed to a decline in homophobia and to greater social acceptance of homosexuality, at least in Western culture. The introduction of the

PaCS

(Pacte civil de solidarité; Civil solidarity pact) domestic partnership proposal in France was in part inspired by a desire to address the problems encountered by homosexuals when confronted with the death of their partner. With the epidemic and the tragedy it engendered, the world of fiction began introducing characters who were portrayed as being less stereotypical. The crisis mobilized the gay community that had been struck head on by the epidemic, resulting in the establishment of numerous and important AIDS organizations, which helped to forge an image of gay solidarity as well as pave the way for gays and lesbians to enter the political arena. In this sense, the battle against AIDS led in some respects to the institutionalization of homosexuality.

We would be well advised not to deny facts, but at the same time we must not forget each setback. While the adoption of PaCS in France—following vitriolic debate in which homophobes in France had their say—was justified based on an acknowledgment of French law to protect the rights of gay and lesbian couples, the arguments of those in favor of it were almost exclusively framed in the tragic context of HIV and AIDS; in this way, the debate moved from the political (regarding the equality of domestic partners, whether gay or straight) to the personal (by invoking compassion for those suffering under the inefficiencies of the health system). If it is true that the AIDS crisis created opportunities for a new representation of gays and lesbians, it must also be noted that this image of homosexuals was more “marketable” because it was sympathetic and indeed tragic. In the end, some wish that discussions of the “exemplary” character of the gay community, underlined again and again by political figures and those in the

media

, would have been an occasion for an analysis of the political context in which gays and lesbians were forced to be “exemplary”: the widespread indifference of governments, the media, and the general public toward the suffering and deaths of thousands of homosexuals during the early years of the epidemic. The gay community acted as it did in the mid-1980s simply because it was forced to; it could not count on others to help. In short, one cannot deny that the tragedy of AIDS contributed to pushing “the homosexual issue” forward and that the two decades since the crisis started were also years in which the gay community made huge strides toward full “liberation.” But at the same time, the price of this “liberation” was dear, and improvements in how mainstream society treats gays and lesbians might best be described in the context of a repentant homophobia.

In industrialized nations, AIDS did not strike randomly, but rather in socially defined categories, starting with male homosexuals. For gay men, the impact of AIDS was intensified by a culture that encouraged multiple partners and sexual experimentation. AIDS itself, however, was not directly related to multiple partners, or to homosexuality itself; HIV is transmitted by specific practices, and therein was the process by which to stop it. In this context, the epidemic’s impact on the gay community was exacerbated by the slowness in setting up public prevention policies around the world.

In France, as well as in most wealthy countries, it was not until the mid-nineties that gay men no longer made up the majority of new AIDS cases. This was due, in part, to the spreading of AIDS to other communities, to the point where those now most affected by it (at least in industrialized cultures) live in socially precarious situations (such as intravenous drug users). Nevertheless, more than half of the 40,000 people who have died in France due to complications from AIDS were homosexual. The epidemic hit the gay community during a time when there was little or no medical response available; and the impact was long-lasting: today there are few gay men of a certain generation who, having lived through the 1980s and 90s, were not tragically affected by AIDS through the loss of friends or lovers.

But the story does not end there; while the gay community was being decimated by AIDS, it also constantly crossed paths with homophobia. Without subscribing to a naïve, unambiguous causality, it can be stated that the AIDS crisis set the stage for a revival of homophobic

rhetoric

, and in turn the homophobic rhetoric exacerbated the AIDS crisis.

It is necessary to note that at the height of the epidemic, there were huge difficulties and delays in disseminating correct preventative information and establishing proper policies. What France went through might shed light on similar experiences elsewhere in the Western world: it was apparent that as long as the epidemic seemed restricted to homosexuals and drug users, governments were reluctant to get involved. A prevention campaign might have been helpful for “queers” and “druggies,” but it would be at the risk of compromising one’s political reputation by being seen as encouraging practices that were questionable at best. It is thus that in France, the government constantly delayed the implementation of a minor legal mechanism that would have at least allowed the advertisement of condoms, prohibited in the country since the 1920s by a law from another age designed to fight a national decline in the birthrate. The 1967 Neuwirth law, which made contraception legal, did not have much impact: the promotion of contraceptive practices remained forbidden, and, consequently, so did the promotion of condoms. It was not until 1986 that it became legal to advertise condoms in France; the very first public prevention campaigns did not appear until a year later in 1987, but it was not until the late 1990s that such campaigns aimed at the general public included characters who could be identified as gay. Until then, government authorities, who had been reluctant to launch any kind of prevention campaign, refused to include the representation of homosexuals in television commercials, posters, or newspaper ads; they claimed these decisions were made to avoid “stigmatizing” the gay community by directly linking homosexuals to the epidemic. In the end, the main consequence of this was to perpetuate the invisibility of homosexuals in the public discourse.

Meanwhile, organizations aimed at fighting AIDS were being established; one of their main goals was to bridge the political gap between public health policy and AIDS. Though the majority of their members were gay, they held different views on the homosexual dimension of the epidemic: on one hand, groups such as AIDES (Association de lutte contre le VIH/Sida et les hepatitis; Association for the Fight Against HIV/ AIDS and Hepatitis), which had established the most important network of gay solidarity in France, preferred not to emphasize the link between homosexuality and AIDS in order to avoid its categorization as the “gay disease” at a time when mainstream society might think that the death of “a few queers” might not seem so bad. On the other hand, groups such as ACT UP underscored the relationship between AIDS and the queer community in order to highlight the government’s inaction on the crisis, and to counter the vicious circle of

shame

in which AIDS sufferers were trapped. The different strategies may have been in conflict with one another, but the groups had common goals: responding to the effects of homophobia on the spread of the epidemic, and finding ways, both politically and physically, in which to treat the afflicted. They also agreed that AIDS revealed the fragility of society, spreading to groups in direct proportion to the level of

discrimination

they had already suffered; and the devastating emotional and social impact of AIDS further worsened that fragility. It became necessary to think about the political and social conditions that allowed AIDS to spread, including the idea that it took root in communities that were unable to resist it, that is to say, wherever the social component was weak or nonexistent. However, this also meant understanding that AIDS was not only symptomatic of a rupture in a community’s well-being, but that it worsened it as well.

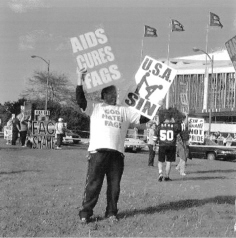

“AIDS Cures Fags”: Preparations for an anti-gay demonstration.

In this context, it was unthinkable to fight AIDS without fighting the homophobic rhetoric that arose and developed along with it during its early years. The ravages of AIDS on the gay community not only failed to silence many homophobes, but gave them a new reason to revive the anti-gay rhetoric that had weakened over time. We can identify some of their motives for this, from the most brutal to the most subtle.

“At-Risk Groups”

On one hand, there is the obvious: HIV is transmitted by high-risk activities, and halting these activities can prevent its spread. On the other hand, there is a persistent myth purporting that HIV is solely an issue for “at-risk groups.” It is well-known that AIDS was first absurdly referred to by the media as “the gay cancer.” Since then, this logic has been repeated elsewhere: AIDS is regularly categorized as the illness of “others,” from whom it is important to protect oneself. It is the “4-H disease”: homosexuals, heroin addicts, Haitians, and hemophiliacs. In this sense, many homophobic views concerning AIDS belong to the more general category of exclusion, which purports to adhere to a policy of AIDS prevention, or imaginary methods of protection, based on the identification and isolation of entire portions of the general population. The French

far right

has thus designated homosexuals and immigrants as the troublemakers; in Japan or in China, AIDS is a Western disease, and in black Africa, a white disease. Each time, the effect of this type of representation has been (and still is in many countries) two-pronged: a denial of the realities of the epidemic on one hand, which legitimizes the absence of a coherent government policy that includes prevention, care, and treatment; and the proliferation of catastrophic discourses on the other, from which exclusionary, discriminatory laws and policies are developed. The anti-AIDS arguments of ultra-orthodox Catholics in France, to cite one example, are symptomatic of this dual dimension: they insist that the epidemic is “marginal” and that it “only kills a very small portion of the population,” (“La marée rose,”

Permanences

[monthly magazine of civic and cultural action, according to Christian and Natural Law], no. 340 [March-April 1997]) thus contesting any attempt at mobilization against it; at the same time, they warn against homosexuality becoming “commonplace,” and advocate discriminatory measures against it. This view is influenced by pseudo-medical, homophobic literature whose main objective is to deconstruct the “myth of heterosexual AIDS.” Such advocates made some inroads politically: in 1991, while France’s penal code was being revised, Senators Sourdille and Jolibois convinced the French senate to adopt two amendments which they claimed were justified by the urgent nature of the AIDS epidemic. The first allowed homosexuality to be named as an aggravating circumstance in crimes and misdemeanors; the second had the effect of recriminalizing homosexuality by reinstituting a different age of consent for gays and lesbians than for heterosexuals. These amendments were later rejected by the National Assembly.

In many countries, in order to contain “at-risk groups,” conservative political leaders, including those on the far right, recommended homophobic public health policies such as the compulsory testing of homosexuals. In France, National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen suggested the establishment of “aidsatoriums,” where those afflicted with HIV or AIDS would be isolated from the greater population. In the United States, Louisiana gubernatorial candidate David Duke made another suggestion: “I believe in the idea of an unerasable tattoo, with AIDS written on it. It would be placed in an intimate area, maybe even in red and black letters. This tattoo would save lives….”