The Dictionary of Homophobia (150 page)

The second historical event is the appearance of

AIDS

in the early 1980s, which forced gays and lesbians to move from fighting for tolerance to the fighting against the

intolerable

. Certainly, this idea of intolerable had been in vogue since the 1970s. But at the dawn of the AIDS crisis, tolerance, understood then as

indifference

, became intolerable as gay activist groups such as ACT UP adopted slogans like “Silence = Death” and “We die, you do nothing.” The issue had been completely turned around. It was no longer a question of fighting repression, but rather mainstream society’s “laissez-faire” attitude toward the AIDS crisis. It was no longer a fight against an active, overt homophobia, but rather a passive one in which “eyes were wide shut.” In short, the pandemic transformed gay and lesbian activism from a fight for difference into a fight against indifference. Here, it is important to remember the gay community’s shifting status in the early 1980s, when the arrival of the “gay cancer” provided a new rationale for the stigmatization of and

discrimination

against gays and lesbians. The AIDS crisis, and its impact on society’s tolerance of gays and lesbians, revealed a fundamental contradiction of all policies of tolerance: How can one be fundamentally tolerant without running the risk of tolerating the intolerable?

The third historical event that ruffled the standard of tolerance is the adoption of the civil solidarity reforms PaCS itself. In a sense, the adoption of PaCS stands as a marker of progressively tolerant liberal policies toward not only homosexuality but private consensual relationships in general. However, at the same time, it raises a legal conundrum. If homosexuality is solely a private and contractual matter, then legalized gay marriage is not possible, since marriage supposes arbitration by a third party, i.e. the state. In this way, the

adoption

rights of gays and lesbians cannot be considered either (children being not only of the private sphere but also partially of the public). In other words, with the adoption of PaCS, tolerance of homosexuality has become incompatible with true legal equality.

Tolerance is always conditional or limited: it is only possible under certain conditions and to a certain extent. More precisely, we could say that there are two types of limitations on tolerance. The negative limitation, of French origin, uses the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen as its foundation: freedom appears as a purely negative notion; one is free to do anything that does not harm others nor disrupt law and order, as defined by the state. The positive limitation, of Anglo-Saxon origin, is based on John Locke’s “A Letter Concerning Toleration”: tolerance is extended to a limited faction of society, and is positively represented and defended by the state. (Locke specifically limits tolerance to all religious beliefs except atheism.) Whatever the case, advocating tolerance in regard to homosexuality undoubtedly conflicts with both of these negative and positive limitations.

Equality between heterosexuals and homosexuals will be achieved when tolerance is no longer limited or qualified or even an issue—just as no one talks about tolerance with regard to heterosexuality. However, it is important to understand the implications of such a proposal. First of all, according Michel Foucault’s proposition in “La Volonté de Savoir” (“The Will to Know”), and virtually every American queer association thereafter, we should refuse to define our individual truth by and through sexuality. Furthermore, renouncing the politics of sexual identity, while allowing for the abandonment of repressive sexual hypotheses, could potentially undermine some of the very foundations of the sexual revolution. Moreover, such a strategic reversal would give credence to the homophobia of indifference: How can one fight AIDS if one refuses to name its first victims? How does one counter the odious likening of homosexuality to

pedophilia

if one refuses to assign a positive and specific definition to all sexual orientations? And how can one defend a progressive liberal policy toward homosexuality if one does not define homosexuality first?

In any case, it is essential to recognize that a criticism of tolerance, which oscillates between affirmation and negation of the definition of homosexuality, is just as fundamentally contradictory as a policy of tolerance, which oscillates between the acceptance and rejection of homosexuality. Thus, it is not possible to support a consistent notion of tolerance in the fight against homophobia as it is constantly altered by context and circumstance. However, it is also likely that the notion of tolerance will continue not only in societies presumed to be intolerant of gays and lesbians but in allegedly tolerant ones as well. All one needs to do is listen to Pope John Paul II, more than four centuries after the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, declare that Catholicism is the only true religion.

Mutatis mutandis

. One can only conclude that the majority of effectively tolerant homophobes will remain tolerant only for as long as they are forced to.

—Pierre Zaoui

Aquinas, Thomas.

Summa theologiae [1266–1272]

. Paris: Le Cerf, 1984. [Published in English as

Summa Theologica

.]

Bossuet, Jacques-Bénigne. “Avertissements aux protestants” (notably numbers 3 and 6). In

OEuvres complètes

. Paris: F. Lachat, 1962. First published in 1689–91.

Boswell, John.

Christianisme, tolérance sociale et homosexualité

. Paris: Gallimard, 1980. [Published in the US as

Christianity, Social tolerance, and Homosexuality

. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1980.]

Diderot, D’Alembert. “Tolérance.” In

L’Encyclopédie

. Paris: Flammarion, 1986.

Foucault, Michel.

La Volonté de savoir

. Paris: Gallimard, 1976.

Halperin, David.

Saint Foucault

. Paris: EPEL, 2000.

Legler, Joseph.

Histoire de la tolérance au siècle de la Réforme

. Paris: Aubier-Montaigne, 1955.

Locke, John.

Lettre sur la tolerance

. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1965. [Published in the US as

John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration

. Edited by John Horton and Susan Mendus. New York : Routledge, 1991.]

Thierry, Patrick.

La Tolérance: société démocratique, opinions, vices et vertus

. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1997.

Voltaire. “Tolérance.” In

Dictionnaire philosophique

. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1964. [Published in the US as

Philosophical Dictionary

. New York: Basic Books, 1962.]

—Abnormal; Heterosexism; Philosophy; Rhetoric; Symbolic Order; Utilitarianism; Violence.

TRANSPHOBIA

In the same way that gay men and lesbians are the targets of homophobia, transsexuals, transgenders, transvestites, drag queens, and drag kings are also the targets of discriminatory treatment. These groups do not primarily identify themselves through a specific sexuality that departs from the heterosexual model. Nonetheless, since the relation between sex, gender, and physical appearance upon which these identities are built continues to undermine the heterocentric establishment, transphobia expresses the hostility and the systematic aversion, be it more or less conscious, to individuals whose identity blurs the lines of sociosexual roles and transgresses the limits between sex and gender.

At the end of the nineteenth century, and in the wake of the studies by Magnus

Hirschfeld

, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, and Albert Moll in

Germany

, as well as Havelock Ellis and Henry Maudsley in

England

, psychiatrists focused on the entirety of recorded sexual pathologies: homosexuality, transvestism, fetishism, bestiality,

exhibitionism, pedophilia

, etc. Beginning with the first scientific observations and the description of these “

perversions

,” categories are established, which lead to the distinctions between the various identities. Transsexuality is then assimilated to newly defined sexual pathologies in the same way as homosexuality and transvestism. In 1949, the American sexologist D.O. Cauldwell, who published a paper entitled “Psychopathia Transexualis” involving the case of a woman who sought a sex change operation, introduced the term “transsexualism.”

Considered ill, individuals who presented gender identity troubles were submitted to medical authorities, who were charged with recommending therapies that would regulate their behavior and identity. From the moment transsexualism or transvestism were officially considered distinct from other deviant behavior, they could be assigned to specific institutional repression. Thereafter, but outside the parameters of the medical establishment, new identity categories began to develop, such as transgender, drag queen, and, most recently, drag king.

However, widely accepted ideas continue to assimilate transgenderism or transsexuality to homosexuality. Understood as “sicknesses,” “depravities,” and “questionable tendencies,” they are in the same way regarded by social norms as strange, eccentric, and perverse. Thus, transphobia and homophobia are frequently confused. Moreover, it is possible to identify an entire repertoire of insults that are aimed simultaneously and interchangeably at homosexuals, transsexuals, and transvestites: “queer,” “poof,” “fag,” “drag queen,” “dyke,” “cocksucker,” et cetera. This assimilation reinforces the idea of belonging to the same community, a “community of insults” some might say, in which particular forms of socialization are developed that are subsequently exposed to the same forms of repression; the 1969

Stonewall

riots being the most famous example. These social groups also share a certain number of demands that are often expressed during Gay Pride (which has become LGBT Pride in many countries), a celebration and visible demonstration of the different facets of the community.

In fact, the expression of transphobia has certain characteristics that are very similar to homophobia, but it also contains elements that correspond to specific characteristics of the group being targeted. Its most brutal and obvious interpretation is, without a doubt, physical

violence

and intimidation; one need only think of the “bashings” and other assaults aimed at transgenders. Certain transsexuals describe the frequently brutal reactions of men who realize that the woman in his arms is not biologically female. The murder of transsexuals is still a common event in some countries, and many live in constant fear of being attacked or killed. In the late 1990s, many of Algeria’s transsexuals (or “creatures,” as they called themselves) fled the country, often at the behest of their families, in the wake of the Algerian Civil War and the persecution of groups that had been previously tolerated.

However, transphobia takes on many other forms, at first sight less overt than physical attacks, verbal assaults or irrational expressions of disgust or revulsion, but which are more insidious, akin to what French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu describes as symbolic violence. For many transsexuals, derision, contempt, repression, and institutionalized discriminatory treatment are manifestations of transphobia experienced on a daily basis.

The situation particular to transsexuals, whose gender identity does not correspond to their birth gender, is a rather explicit example of the institutionalization of transphobia. Moreover, the social relationships that transsexuals must sever in order to affirm their identity and their physical transformation—be it

family, school, work

, or, in some cases, country—are just so many circumstances in which the cultural aspects of transphobia are expressed. They constitute a social and political mechanism for

discrimination

. In fact, activities such as getting a passport or a new social insurance number, requests for political asylum in cases of expulsion or deportation, court appearances, and lodging complaints in cases of assault, are, for transsexuals, simply more opportunities to experience transphobia.

From a legal standpoint, the courts have tended to latently support the social ostracism of transsexuals, or created the conditions for its expression. As the French legal establishment is silent on the transsexual question (as well as the question of sex change), and French law does not define sex or gender, it is

jurisprudence

that, above all, establishes the basis of consideration and makes decisions regarding transsexuals. Thus, in

France

, until recently, transsexuals could only acquire non-gender-specific names such as Pat or Chris. Furthermore, a requested change in one’s civil status— a determining issue for transsexuals, since it presides over the identification of every official document and, consequently, the determination of rights, notably with regard to family law—remains particularly difficult to obtain if one does not undergo a hormonal-surgical sex change. It is currently evident that the state and society push those who have gender identity issues toward surgery, which is particularly extensive; some transsexuals admit having undergone surgery in order to obtain official identification that reflected their gender identity and appearance.

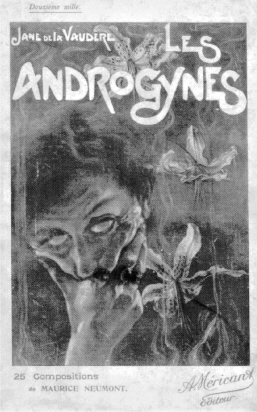

Plato’s “Myth of the Androgyne” and new medical theories on the third sex blend in order to construct a particularly anguishing image. The catalog featuring this novel explains quite clearly the breadth of this work, published in 1902. “It was necessary to condemn these sexual dead-ends, not in a book of unrealistic morality, but in an attractive, captivating novel, by opposing shameful vice with triumphant love, love both frantic and passionate, which is the great savior of our race and the purifier of all carnal hideousness. This novel contains somber paintings, images of murder and of nightmare, but also pages flowered with delicate and burning passion.”