The Dictionary of Homophobia (71 page)

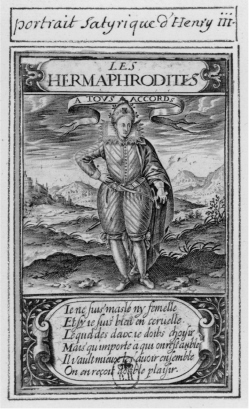

Satirical portrait of Henri III.

Les Hermaphrodites

: “I am neither male nor female….” Sexual and moral duplicity join together in denouncing the king.

How then did Henri III end up as the “Bugger King” in the collective imagination? If his critics were homophobic, the cultural, political, and religious aspects of this metamorphosis are then greater than the specific issue of sexuality.

Well in advance of the great Versailles machinery, the last Valois king presided over a first attempt at domesticating or standardizing the moral behavior of the court, including advice on bodily hygiene and dinner table manners. However, the use of cutlery, soap, and a white powder for teeth, and the changing of clothes between day and evening, appeared to be eccentric to most, and went against the rustic tendencies that were common outside the immediate royal entourage; this eccentricity was somehow linked to sexual deviance. Added to this was a certain amount of anti-Italian xenophobia, given that Henri III’s mother was Catherine of Medici, a source of great inspiration for him. The combination thus established presented another opportunity to discredit him politically. In choosing “favorites” from middle nobility, the king tried to bypass the influence of cliques from the high aristocracy, first and foremost, the House of Guise. As this was accompanied by an apparent will to distance himself from the royal persona, the resulting hostility of the high artistocracy was based on the idea that a king who hides himself must have something to hide. As for the then-frequent link made between the king and sodomy and, by association, heresy, idolatry, and witchcraft, it had the effect of making the king’s piety seem less sincere and excluded him from religious matters, which were deemed better dealt with by the House of Guise. Under these conditions, one could say that Henri III was a victim of his adversaries’ homophobia, one common and useful example of the polymorphic hostility expressed toward a king who was ahead of his time.

—Laurent Avezou

Chevallier, Pierre.

Henri III, roi shakespearien

. Paris: Fayard, 1985.

Godard, Didier.

L’Autre Faust

,

l’homosexualité masculine pendant la Renaissance

. Montblanc: H & O Editions, 2001.

Lever, Maurice.

Les Bûchers de Sodome

. Paris: Fayard, 1985.

Poirier, Gérard.

L’Homosexualité dans l’imaginaire de la Renaissance

. Paris: Confluences-Champion, 1996.

Solnon, Jean-François.

Henri III

. Paris: Perrin, 2001.

—Favorites; France; History; Literature; Monsieur; Scandal.

HERESY

Homosexuality has often been relegated to a form of heresy, and treated as such. In the Bible, St

Paul

identifies idolaters, effeminates, and pederasts (1 Cor 6:9–10) as those who have cut themselves off from God, and for whom the kingdom of God will thus be forbidden. Based on these affirmations, as well as the episode of

Sodom

(Gn 19) and the Apocalypse of John (Ap 21), it was determined that killing Sodomites by fire was the only means of confirming their spiritual death: the world needed to be purified of their presence. Middle Age

theologians

prolonged this Biblical tradition. For Thomas Aquinas, homosexual acts were an insult to God’s willed nature and order; as such, sodomites were explicitly rejecting the Christian community in the same way as idolaters, pagans, and heretics; clearly, they were “heretics in love.” Conversely, those accused of heresy were often referred to as sodomites and accused of acts

against nature

. These interpretations were based on the idea of the diabolical act. By definition, the devil acted “unnaturally” and was ready for all kind of excesses. The trials of those accused of witchcraft corroborated the trials of those accused of heresy and vice versa; in both cases, if found guilty, the penalty was that of purifying fire.

It was in this spirit of a return to the orthodoxy and purity of Christianity that the

Inquisition

was established at the beginning of the thirteenth century, and quickly entrusted to the Dominican Order. Today it is difficult to untangle the various reasons for condemnation, which often came about as a result of torture to loosen tongues, but one thing is clear: the war against homosexuality was also a fight to reinforce religious doctrine. The Manicheans, a Christian sect, were persecuted by the Byzantine empire before finding sanctuary in Bulgaria. Based on their apparent behavior, they were considered buggers, implying they were both sodomites and heretics. Similarly, the Albigensian sect, active at the beginning of the thirteenth century but also founded on ancient Manichean ideas, scorned matter, body, and procreation. Sexual relations were tolerated provided no procreation was involved; because of this, the Albigensians were suspected of favoring homosexual relations.

The Templars affair in the thirteenth century, in which a number of French Templars were arrested and charged with numerous heresies under the direction of King Philip IV as a means of ridding the country of the Templars, is a good example of the link between homophobia and accusations of heresy, as the order stood accused of both sodomy and idolatry at the same time. Their accusers obtained “proof” of unnatural acts through torture, a common practice. Under duress, many Templars admitted to having been kissed on the mouth when admitted to the order, or “having received a kiss on the arm, on the lower end of the spine, on the umbilicus and on the mouth by candidates.” They also admitted that “if any heat moved them to incontinence, they had permission to spend it with other brothers,” or even that “many among them, by way of sodomy, sleep sexually with each other.” A few retracted their statements, but to no avail; such confessions were used as evidence of heresy, leading to dozens of Templars to be burned at the stake. The Vienna Council, which dissolved the order in 1312, justified it on the grounds that the Templars “had fallen in an abominable apostasy crime against our Lord Jesus Christ, in the detestable

vice

of idolatry, and the atrocious fault of sodomites and diverse heresies.” The Council commission charged with the responsibility of examining the transgressions of the Templars eventually capitulated to the demands of King Philip IV. Still subject to torture, monks confessed crimes against nature in addition to heresy, according to Council texts. Whatever the truth was, one might think that heresy and idolatry were sufficiently serious offenses to justify their arrest, but in order to make the Templars disappear, Philip IV and his charges had to hit harder; the further accusation of crimes against nature added fuel to the fire. As a result, the king was justified in seizing their property, and Pope Clement V could abide by it without (too much) loss of face. It is important to note that homophobia was so anchored in the Church and the Civil Power’s way of thinking that it was used to justify virtually any kind of arrest or punishment.

While the definition of crimes against nature was sufficiently clear, their link to other crimes that were much more of a threat to the Church, especially heresy, is difficult to understand. The fact remains, however, that those accused of these connected crimes, those so-called sodomites, were forced to endure torture, persecution, and in certain cases, being burned at the stake.

—Thierry Revol

Alberigo, Giuseppe, ed.

Les Conciles oecuméniques

. Vol. II-1: “Les décrets.” Paris: Le Cerf, 1994.

Boswell, John.

Christianisme, tolérance sociale et homosexualité

. Paris: Gallimard, 1985. [Published in the US as

Homosexuality, Intolerance, and Christianity

. New York: Scholarship Committee, Gay Academic Union, 1981.]

Gaignebet, Claude, and Dominique Lajoux.

Art profane et religion populaire au Moyen Age

. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1985.

Lever, Maurice.

Les Bûchers de Sodome

. Paris: Fayard, 1985.

—Against Nature; Bible, the; Catholic Church, the; Damien, Peter; Inquisition; Judaism; Paul; Rhetoric; Sodom and Gomorrah; Theology; Vice; Violence.

HETEROCENTRISM.

See

Heterosexism

HETERONORMATIVITY.

See

Heterosexism

HETEROPHOBIA

It might seem paradoxical to reflect on a concept without proven linguistic existence. One dictionary defines heterosexuality as “the normal sexuality of the heterosexual,” i.e. a characteristic of one “who feels a normal sexual preference for an individual of the opposite sex.” Homosexuality, on the other hand, is defined as “tendency or behavior of homosexuals.” These conventions are so widespread now as to be quasi tautological: the adjective “normal,” used to characterize heterosexuality does not, in this instance, mean “habitual” or “common,” but functions to underline the normality and conformity of the heterosexual. Facing so much normality, we can understand why no one asks if “homophobia” has its reciprocal. The notion of heterophobia will likely be thought of as superfluous, doubtful, incongruent, or at worst, completely suspicious.

Let us be clear that it does not work to impose a definition of the term heterophobia, which has already been interpreted in numerous ways (Jacques Tarnero makes it a synonym for racism, a form of hatred of the other), and whose real existence is problematic. Anyone who can grasp its reality and evaluate its importance can assume the indisputable existence of heterophobic practices. Unlike homophobia, heterophobia does not hold on to a discourse on axiological order, whether for or against, as writer Erik Rémès suggested in a May 7, 2001 letter published in

Ibiza News

. He defined heterophobia as the “rejection or fear of heterosexuality, including a repulsion toward heterosexual fantasies, desires, and behaviors [as well as] discriminatory attitudes toward individuals of a heterosexual orientation.”

Heterophobia will be examined here as a theoretical concept in order to better question the absence of the term in a system that both legitimizes or discriminates against representations of sexuality: what is represented by this void, so to speak, and what new perspective does it reveal about the phenomenon of homophobia?

It is reasonable to assume that as a result of the physical and emotional

violence

perpetrated against homosexuals throughout history—which to this day can still result in all manner of stigmatization, imprisonment, and even death—that homosexuals might naturally feel as hateful and bitter toward heterosexuals in much the same way. How is it possible, then, that the reciprocal of this

discrimination

, i.e. heterophobia, has never taken hold? Isn’t it strange that, with a few exceptions, homosexuals have not engaged in widespread reactionary violence as a result of their treatment, as has been the case of blacks through their history or for Jews following World War II and the Holocaust?

Certainly, it seems that in the history of homosexuals, liberation strategies have not included what could be construed as heterophobia. In fact, many gays and lesbians actively oppose the idea of heterophobia, which they believe contradicts the very values on which gay and lesbian identity is based, including a plea for

tolerance

toward all others, regardless of sexual preference. In this sense, to become heterophobic would invalidate their demands for equal rights, respect, and acknowledgment. Nevertheless, one can see traces of heterophobia in the behavior and discourse of certain gays and lesbians, whether it be verbal abuse (such as “heterocops” and “heterrorists,” during the days of the FHAR, the Homosexual Revolutionary Action Front, a French activist group founded in 1971, or “breeders,” in English); insults and caricatures that convey, under the guise of humor, a certain resentment; or myths and stories that create a “parallel universe.” In this last case, heterosexuality can be excluded completely, such as in certain reformulations of the myth of the Amazons, or it can depict a world in which homosexuals possess the same phobic traits as their hetero counterparts: in his 1999 film

Shame No More,

director John Krokidas portrayed an idyllic small town whose inhabitants are all homosexual. When a male couple suspects their son is heterosexual, they are determined to return the young deviant back to normality. It should be mentioned that writings which are explicitly heterophobic are rare: one such case is Hervé Brizon’s 2000 French novel

La Vie rêvée de sainte Tapiole

(The dream life of Saint Tapiole), a zany story about a gay militant terrorist who launches a plan to destroy the symbolic sites of heterocracy.

If there are indeed examples of real heterophobic responses in the world, however, we must note that they are not sufficient to legitimize heterophobia’s presence in any significant way. Furthermore, we can observe that the theme of homosexual violence is an ambiguous subject in

literature

and in

cinema

. One is conscious of the fascination provoked by stories featuring gay killers (such as in Claire Denis’s 1994 film

J’ai pas sommeil

, or

I Can’t Sleep

) or by the stereotype of homosexual love stories that revolve around a crime (such as Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 film

Rope

). These examples illustrate the common depiction of homosexuals as evil, even

criminal

characters. However, they are not heterophobic because their behavior is not in response to heterosexuality as such. Furthermore, they sometimes commit violence against their will, as in Jean Genet’s 1947 novel

Querelle of Brest

(the murder of the first Armenian lover), just as gays themselves are often the first targets of camp humor that takes the form of self-deprecation. Finally, for the most part, the depiction of alternative worlds that oppose the heterosexist universe have first and foremost a critical function; they do not represent a true agenda but are aimed solely at provoking a change in the audience’s perspective, albeit fictional. This is what the character of Arnold does in Harvey Fierstein’s 1978 play (and film)

Torch Song Trilogy

when, instead of arguing with his mother, he asks her to imagine a world in which heterosexuals are bombarded with discourses, books, and broadcasts that incessantly demand, “You’ve got to be gay!”