The Dictionary of Homophobia (80 page)

Borrillo, Daniel.

L’Homophobie

. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 2000.

———. “L’Homophobie dans le discours des juristes.” In

Homosexualités: expression/répression

. Edited by Louis-Georges Tin. Paris: Stock, 2000.

———, and Pierre Lascoumes

,

eds.

L’Homophobie: comment la définir, comment la combattre

. Paris: Ed. Prochoix, 1999.

Burn Shawn, Meghan. “Heterosexuals’ Use of ‘Fag’ and ‘Queer’ to Deride One Another: A Contribution to Heterosexism and Stigma,”

Journal of Homosexuality

40, no. 2.

Delor, François.

Homosexualité, ordre symbolique, injure et discrimination: Impasses et destins des expériences érotiques minoritaires dans l’espace social et poliitique.

Brussels: Labor, 2003.

Douglas, Mary.

De la souillure

. Paris: La Découverte, 1992. [Published in the UK as

Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo

. London, Routledge & K. Paul, 1966.]

Eribon, Didier. “Ce que l’injure me dit.” In

L’Homophobie: comment la définir, comment la combattre

. Reprinted in

Papiers d’identités. Interventions sur la question gay

. Paris: Fayard, 2000.

———.

Réflexions sur la question gay

. Particularly, “Un monde d’injures. Paris: Fayard, 1999. [Published in the US as

Insult and the Making of the Gay Self

. Durham, NC: Duke Univ. Press, 2004.]

Goffman, Erving.

Stigmate, les usages sociaux des handicaps

. Paris: Minuit, 1975. [Published in the US as

Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity

. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963.]

—Abnormal; Discrimination; Humor; Rh

e

toric; School; Shame; Violence; Vocabulary.

INVERSION

In the analysis of the social structure of homophobia, the issue of homosexuality as sexual “inversion”—i.e. a deviation from the sexual norm, in which gay men have female characteristics and vice versa—is a complex subject. The “right” to male effeminacy—the physical behavior behind the stereotype of the “queen,” and once defined as a pathology by medicine—has been regularly defended by homosexuals over time, from the first German movement at the end of the nineteenth century, to the gay liberation trend of the 1970s, to the AIDS-related activism of ACT UP in the 1980s. The quasi-technical term “inversion” was even the title of one of the first gay magazines in France, during the inter-war period.

The image of the invert was not a medical “invention” at all, however. Historical works on eighteenth-century France and England clearly show that the first gay “subcultures” were based in part around effeminacy and transvestism, almost a century before doctors would begin looking for the morphological, physiological, or psychological characteristics of the opposite sex in homosexual men and women.

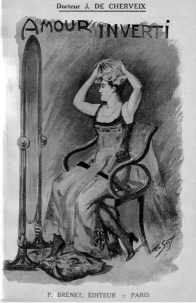

The cover of a novel by Dr J. de Cherveix,

Amour inverti

, published in 1907.

The medical theories constructed around the idea of inversion refer to Austro-German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s classifications of homosexuals, gay German sexologist Magnus

Hirschfeld

’s theory of a third sex, and research based on organotherapies and

endocrinology

. All of these have their origins (more or less) in the writing of nineteenth-century lawyer and gay pioneer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs of Germany, the first “militant” for the gay and lesbian cause, who between 1864 and 1879 published a series of essays justifying “Uranian” love (that is, homosexual), with the argument that men in these kinds of relationships possessed “a female psyche in a male body.”

But the issue of inversion goes far beyond the role played by medicine in the social construction of homosexuality and homophobia. Over time, changes in the representations of the masculine and feminine genders resulted in many people no longer thinking of and/ or perceiving themselves as being completely man or woman, based on their attraction to people of the same sex. Medicine merely provided confirmation (and not without contradictory debate) of this representation which many homosexuals already had of themselves. However, by presenting this idea as “scientific truth,” medicine helped to perpetuate the stereotype of the “queen.”

—Pierre-Olivier de Busscher

Charcot, Jean-Martin, and Victor Magnan. “Inversion du sens génital et autres perversions sexuelles,”

Archives de neurologie,

no. 7,12 (1882).

Kennedy, Hubert.

Ulrichs:The Life and Works of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, Pioneer of the Modern Gay Movement

. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1988.

Lhomond, Brigitte. “Un, deux, trois sexes: l’homosexualité comme mélange.” In

Actes du colloque international Homosexualité et Lesbianisme: mythes, mémoires, historiographies

. Edited by GREH et al. Lille: GayKitschCamp, 1989.

Rosario,Vernon. “Inversion’s Histories/History’s Inversions: Novelizing Fin-de-Siècle Homosexuality.” In

Science and Homosexualities

. New York/London: Routledge, 1997.

Spiess, Camille.

L’Inversion sexuelle

. Paris: L’Athanor/L’En Dehors, 1930.

—Biology; Caricature; Degeneracy; Endocrinology; Ex-Gay; Fascism; Gender Differences; Genetics; Himmler, Heinrich; Hirschfeld, Magnus; Literature; Medicine; Medicine, Legal; Perversions; Psychiatry; Psychoanalysis; Transphobia; Treatment.

INVISIBILITY.

See

Closet

IRELAND

On September 10, 1982, a thirty-two-year-old man was killed in a municipal park in the city of Dublin by a group of youths who, on their own admission, were out gay bashing. Several members of the group declared as well that they had beaten up twenty “poofs” in the weeks prior to the murder of Declan Flynn, and that they had hunted down over 150 homosexuals the year before.

During the trial of Flynn’s murderers, Anthony Maher, a young eighteen-year-old man, declared, “There were a bunch of us out beating up queers for the past few weeks. But we didn’t want to kill Mr Flynn. I thought he was just a gay who was there in the park to meet other gays.” This was the strategy of his defense, paradoxical, but it paid off all the same in the end. He also pretended to have believed that Declan Flynn was a heterosexual, in order to present his action as an error, a misunderstanding, regrettable for all that, because he would, of course, have never killed a heterosexual. On March 8, 1983, six months after the murder of Declan Flynn, the five murderers were brought before Dublin’s Central Criminal Court. The judge, Mr Gannon, suspended their sentences. That night, the murderers, their families, and their friends organized a march with torches to celebrate the victory at the very scene of the crime. A few months later, the same judge ordered a sentence of six months in jail for the theft of a purse. With this judgment, the Irish authorities seemed to officially ratify a violent homophobic act. Nevertheless, the government was severely criticized in the aftermath, and the whole process launched the gay pride movement in Ireland, as it revealed the treatment that homosexuals could expect in this country, under the “protection” of justice.

The

decriminalization

of homosexual relations in Ireland did not take place until June 1993. Prior to that date, sexual relations between men constituted a crime punishable by

prison

, though the law did not take into account relations between women. The history of homophobia in Ireland is completely hidden by the history of English colonization, as well as by the close and complexities between the state and the Catholic Church.

The first significant civil law against homosexuality in England appeared in 1533 under Henry VIII. The Buggery Act made sodomy a crime punishable by death, and despite being abrogated and reinstated several times during the years that followed, it was finally reactivated and extended to all British colonies in 1563 by Elizabeth I, the daughter of Henry VIII. The Buggery Act was adopted, often word for word, by the first thirteen colonies of America, and sodomy was thus punishable by death. The fist Irish victim was the Bishop John Atherton who, in an ironic tragedy, after noting that the law did not apply to Ireland organized a “Campaign to save Ireland from sodomy.” However, this campaign was so effective that he would pay for it with his own life, himself accused and found guilty of sodomy.

The monastic and penitentiary tradition in Ireland had already influenced the English thinking. Manuals of penance circulated in the puritan Irish Celtic Churches, and their influence was known as far as England, France, and Germany from the early Middle Ages. Every homosexual act was ranked as being more or less sinful, according to its character. The base chastisements were the exclusion from the sacrament, auto-mortification (the youngest being hit by rods by older clerics), and a diet of dry bread and water on holy days, with the main difference between punishments being the duration of their application.

After England’s colonization of Ireland, the Church was able to increase its hold on the Irish people. The only choice thereafter was the following: allegiance to the crown or allegiance to the Catholic Church. Catholicism became the only possible expression of Irish autonomy. Over time, Irish nationalism would become more and more closely tied to the teachings of the Irish Catholic Church and, in 1919, canon law became the principal influence on the constitution and the government of the first Irish Republic.

Homosexuality was actively fought within the Irish Republican Army (IRA). During the 1970s and the early 80s, those IRA members imprisoned in the North’s H-Blocks literally ostracized those of their comrades who they perceived as homosexuals. To this effect, Brend’ McClenaghan recounts: “When I would come down into the ‘ablutions’ room, the men would back away from the sinks, showers, and urinals, keeping away from me until I left.” These homosexual prisoners were forced to leave the “republican” quarters of the prison, in this way losing their status of political prisoner that the members of the IRA could claim. Interestingly, Sinn Fein, the political party with close ties to the IRA, was the first to adopt a policy of equality for gays and lesbians at the end of the 90s.

Several centuries earlier, in his

Summa Theologica

, St Thomas Aquinas, whose ideas still today constitute the foundation of the Catholic Church’s position against homosexuality, claimed to have established a rational basis for anti-homosexual prejudice by making the greatest hedonistic crime the sin

against nature

. According to this

philosophy

, reason designates procreation as the unique goal of sexual activity, and this condemnation of homosexuality became the source of all theological discussion on the subject.

The first Irish government in 1919, not content to simply renew this philosophy in harmony with the powerful Catholic Church of the era, decided instead to maintain the English laws against homosexuality, inherited directly from the Buggery Act of 1533. The Labouchere Amendment in 1885, which criminalized “acts of gross indecency between men,” was adopted into Irish law, as well as the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act. These were the same laws used to condemn the Dublin-born Oscar

Wilde

to two years of hard labor. The

police

and the law in Ireland were undoubtedly less brutal than in England, but these laws still set the tone for the lives of Irish homosexuals throughout the twentieth century.

But homophobia also acted through socio-economic

discrimination

, which is still justified today based on the archaisms of canon law. Though modeled after the concept of cohabitating heterosexual couples, gay and lesbian couples could not enjoy the same economic benefits that married couples are legally granted in regards to taxes, insurance, pension, legacy, and mortgage.

In the years leading up to

decriminalization

in 1993, as in many other countries,

AIDS

began to foster homophobic discourse and practices. In Ireland, unlike many other countries, homosexual relations were still illegal, so the implications of AIDS were different. Given that in other countries certain conservatives were trying to propose new homophobic so-called “public health” laws to protect the population from AIDS, why would the Irish government want to abolish the law of 1885?

The fact that the laws of 1861 and 1885 were abrogated in the context of the AIDS epidemic, during a time when hostility against homosexuals was undoubtedly at its highest in Ireland, reveals nonetheless what kind of impact AIDS had on the legitimacy of the gay movement in Ireland. The high number of gays who contracted AIDS in the USA was often used to justify obstructions of personal freedoms, for example when the bathhouses were closed in San Francisco in 1984. However, in Ireland, AIDS during these years affected drug addicts far more than it did gays, and thus could not justify maintaining

criminalization

. The Gay and Lesbian Equality Network joined the campaign for decriminalization and quickly made AIDS into “another reason for the abolishment and not the conservation of those laws actually in place.” In Ireland, AIDS would not hinder the struggle for the reformation of the laws and for equality.