The Dictionary of Homophobia (91 page)

Guillaumin, Colette.

Sexe, race, et pratique du pouvoir—L’idée de nature

. Paris: Côté-Femmes Editions, 1992. [Published in English as

Racism, Sexism, Power and Ideology

. New York: Routledge, 1995.]

Lesselier, Claudie. “Formes de résistance et d’expression lesbienne: dans les années 1950 et 1960 en France.” In

Homosexualités: expression/répression

. Edited by Louis-Georges Tin. Paris: Stock, 2000.

Millett, Kate.

La Politique du mâle

. Paris: Stock, 1971.

Matthieu, Nicole-Claude.

L’Anatomie politique

. Paris: Côté-Femmes Editions, 1991.

Rich, Adrienne. “La Contrainte à l’hétérosexualité et l’existence lesbienne.”

Nouvelles questions féministes

, no. 1 (1981). [Published in the US as “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Experience,”

Signs

5, no. 4 (Summer 1980).]

Russel, Diana E. H., and Nicole Van de Ven.

The Proceeding of the International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women

.

Wittig, Monique.

La Pensée straight

. Paris: Balland, 2001.

—Biphobia; Gayphobia; Heterophobia; Heterosexism; Radclyffe Hall, Marguerite; Rhetoric; Sappho; Transphobia.

LITERATURE

There is a persistent assumption that literary milieus are free of the rigors of homophobia and among the few venues in which homosexuals can freely express themselves. However, this popular opinion misunderstands the conditions under which most literary works of the past were produced. It neglects to take into consideration the fate suffered by homosexual authors from different eras, such as Théophile de

Viau

, Oscar

Wilde

, and Reinaldo

Arenas

. Far from being spared from homophobia, on the contrary, they were particularly exposed to it, due to their notoriety as writers. In reality, many authors suffered from this experience. Beyond those who were charged with crimes, found guilty, and jailed, one must also include those who were never apprehended nor condemned, but who nevertheless had to suffer the hardship of social and moral constraints exercised against them because of their homosexuality; these writers include Giacomo Leopardi, Nikolai Gogol, Tennessee Williams, Thomas Mann, Julien Green, and

Radclyffe Hall

, an open lesbian who was forced to endure the ordeal of

scandal

as a result.

Homophobic discourses and practices in the literary world have not been thoroughly explored by scholars, and while it is surely difficult to propose a unified hypothesis on the subject, it is possible to shed light on it. Homophobic logic in literature operates on two distinct levels: by authors who claim to unmask homosexuality in order to properly denounce it in accordance with morality; and by literary editors who try to mask homosexuality when it appears in the works of others, again in accordance with morality.

For authors, this logic results in the production of a discourse against homosexuality, while for editors, it is the dismantling or transformation of a work to make homosexuality appear less attractive. Discursive production on one hand, reduction on the other; it is not uncommon for such seemingly opposite mechanisms to be complementary to one another while working toward the same goal. As a consequence, one can say that a homophobic poetics exists on one hand, and a philological homophobia on the other; both contribute to the assignment of homosexuality to a predetermined literary space.

From the Homophobic Poetic …

This poetics of homophobic discourses through the centuries has succeeded in adjusting its literary means to its ideological objectives. In this way, it has often employed the genre of satire in order to intensify the vigor of its homophobic attacks. Generally, such satires portray their subjects in a negative light by saddling them with morals that are judged loathsome; further, it tends to draw on archetypal homosexual behavior, dwelling on small details of character which claim to be revealing. One common means was to depict homosexuality in the guise of the effeminate man or the manly woman. Added to this was a cheerful narrative tone, thereby giving the appearance of levity to comments and situations that were often quite heinous. Satire was thus the faux mirror of “truth” which allowed the symbolic and joyful killing of stigmatized persons.

This is how

Henri III

of France was denounced by numerous poets in the sixteenth century, such Pierre de Ronsard and Agrippa d’Aubigné, who devoted numerous lines of

Les Tragiques,

in which he evoked “the effeminate gesture, Sardanapale’s eye / … as at first, everyone was in difficulty / if he say a woman King or a man Queen.” Similarly, in the following century, Cardinal Mazarin became a favorite target of satirists when he was accused of

vice

, a fact which French dramatist Paul Scarron, in his famous

Mazarinade,

did not hesitate to shout from the rooftops. According to Scarron, Mazarin would be “Sodom’s wand sergeant / exploiting the realm everywhere / Devil buggering, buggered devil / and bugger to the highest degree / bugger with hair and bugger with feather / bugger in big and small volume / Bugger sodomizing the State / and bugger with the most carats….” Whether the accusation of homosexuality was true or not, these satires permitted of the subject’s symbolic beating or murder, regardless of his status.

That said, homophobic satire remained common throughout the twentieth century, mostly in lighthearted stage comedies which evoke over-the-top queens or young men who are “a little like that.” In fact, the homosexual (the gay man, because the lesbian does not appear often in these representations) is frequently present, but always in a secondary role. He has a definite function: he is the proscribed entertainer on duty, performing the same function as the idiot in medieval theater, or the harlequin in the

commedia dell’arte

. Beyond provoking laughter, this character is a deeply anguished figure, and he exorcises this anguish by laughing at the top of his voice. The “queen” character is easily recognizable by his mannerisms, his melodramatic responses, his limp wrists, and his eccentric, colorful clothes: the social stereotype becomes a theatrical and literary type, unless it is the reverse. Even if theatrical history grants little importance to such plays, they nonetheless played an important role in the popular cultural representation of homosexuals; many audience members were only acquainted with homosexuals through their appearance in such plays. Under these conditions, and in the context of homophobic satire, homosexuality was necessarily depicted as a comical yet distressing reality, familiar yet troubling, as shown in Jean Cau’s 1973 play, in which the protagonist learns that his wife is having an affair with his best friend and, at the height of his misery, that his son “is like that,” the “illness” having spread throughout the entire country; hence the play’s title,

Pauvre France

(Poor France). But the pinnacle of the genre was reached with Jean Poiret’s 1973 play

La Cage aux Folles,

in which French actor Michel Serrault appeared over 1,500 times (a film version was released in 1978, followed by a stage musical a few years later, both enjoyed incredible commercial success in France, the United States, and elsewhere). Its two characters, the same-sex couple Renato and Albin, a.k.a. Zaza (a drag queen), were touching but pathetic; at the same time, the popularity of the play (and film) largely served to perpetuate stereotypes, contributing further to popular homophobia.

Besides satire, the homophobic poetic also developed two other trends: one, the religious, moralizing sermon, and the other, didactic, scholarly literature. These two trends have radically different approaches. The moralizing discourse willfully employs maxims, biblical references, and hyperbole to support its themes; the scholarly discourse is more tempered, using rigorous terminology and methodology to further its claims. What unites these two styles, however, is their serious and somber approach to their subject, unlike satire. From St Thomas Aquinas’

Summa théologica

to André Breton’s “Recherches sur la sexualité” (Research on sexuality), from Father Garasse’s

La Doctrine curieuse

(The curious doctrine) to Etienne Pivert de Senancour’s

De l’amour

(On love) to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s

Amour et marriage

(Love and marriage), these works found ways to perpetuate, even if incidentally, the most obscurant prejudices toward homosexuality. Voltaire himself, in his

Lettres sur la justice

(Letters on justice), saw in sodomy “a low and disgusting

vice

whose real punishment is scorn,” a passing of judgment that he confirmed in the article “Amour socratique” (Socratic love) in the

Dictionnaire philosophique

(The philosophical dictionary), while at the same time admitting that it did not warrant

prison.

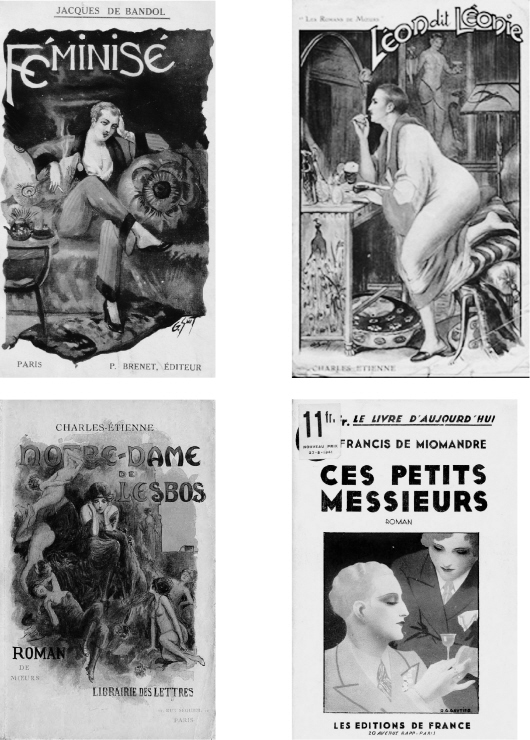

In novels, however, homophobic discourse revealed itself to be more difficult to analyze due to distortions introduced through the device of fiction. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, a series of popular novels was published in France in which homosexuality was presented in a stereotyped, unhealthy way, albeit seductive at times: novels such as Gabriel Fauré’s

La Dernière journée de Sapphô

(The last day of Sappho) (1901), Dr J de Cherveix’s

Amour inverti

(Inverted love) (1907), Charles-Étienne’s

Notre Dame de Lesbos

(1924) and

Léon dit Léonie

(1922), Victor Margeuritte’s famous

La Garçonne

(The bachelor girl) (1922), Willy and Menalkas’s

L’Ersatz d’amour

(The ersatz of love) (1922), and Charles-Noël Renard’s

Les Androphobes

(1930). These novels superimposed successive layers of the homophobic imagination: the ancient courtesan with doubtful morals, the

heretic

from the Middle Ages, the

debauched

aristocrat from the Ancien Régime, the androgyne of the nineteenth century, and the invert—the figure of the third sex, as described in pseudo-scientific theories of the era: all of these types and more appeared through the artistic gaze of a languid prose that seemed to take pleasure in evoking what it was in fact stigmatizing.

To this effect, Marcel Proust’s master work

A la recherche du temps perdu

(

Remembrance of Things

Past) constitutes a particularly emblematic case due to its essential ambiguity. In his novels, homosexuality is tied to the dark legend of

Sodom and Gomorrah;

it appears as a trait of slavish servants such as Jupien, and decadent aristocrats such as Charlus, and is depicted as it meanders tortuously in a somber and long descent to Hell, which ends in the final revelation of

Temps retrouvé

(

Past Recaptured

), when all of the inverts finally drop their masks and reveal their degradation. As complex and seductive as these characters might seem, they are nonetheless branded by the ancestral curse which appears to weigh heavily on them.

In this respect, the literary prism through which the narrator depicts homosexuality is clearly linked to all three genres of the homophobic poetic: satire, moral and religious tradition, and finally, medical opinion of the time that understood

inversion

to be a disease, an opinion shared by hallowed dissertations on the subject of

Sodom and Gomorrah

. But in reality,

Temps perdu

is neither a satire, nor a moral or science-based discourse: it is a work of fiction that orchestrates a number of social discourses in a polyphonic ensemble, which can be read in multiple ways.

However, this vision of homosexuality, thoroughly negative though refined—by a gay author, no less— certainly annoyed André

Gide

, himself a homosexual: “This offending of the truth is likely to please everyone: the heterosexual, whose warnings it justifies and whose loathings it flatters; and the others, who will now have an alibi and who will benefit by their scant resemblance to those whom he portrays. In short, given the general tendency to cowardice, I do not know any writing which is more likely than Proust’s

Sodom

to encourage wrong-headed thinking.” And according to Gaston Gallimard, Gide even said to Proust: “You have driven back the question to where it was fifty years ago.” As a matter of fact, before Proust’s homosexuality was known, his work was understood as that of an austere moralist. “To repress a vice, one must have the courage to denounce it by making it odious,” Paul de Bellen wrote about him in the anti-Semetic periodical

La Libre Parole,

completely satisfied with the “odious” portraiture of inverts created by Proust. For Roger Allard, the work’s greatest merit was that it “breaks the aesthetic charm of sexual inversion.” And for Paul Souday, Proust was to be commended because he “does not directly describe these delinquents’ excesses, but studies their psychology in relation to their

vice

.” In all, homophobic prejudices felt completely reassured by

Temps perdu

.

At the end of the nineteenth century, and the beginning of the twentieth, a whole body of literature took aim at homosexuals, generally presented as intersexual, degenerate, and decadent beings.