The Dirt (31 page)

Authors: Tommy Lee

Before Tommy’s wedding, I had managed to keep my habit a secret because I hardly saw anyone in the band. The gang was now split into different houses in different parts of the city. We were still doing pretty much the same thing we did when we all lived in an apartment together: waking up, getting fucked up, then going to sleep and starting all over again. But the difference was that we weren’t doing it with each other. Tommy was in Heatherland, living in a multimillion-dollar home in a private neighborhood with security gates. He was so excited that one of his neighbors was an investment banker making forty-five million dollars a year and another was a lawyer handling major murder cases. But all I could think was, “These people used to be our enemies.” Vince was either in jail or hanging out at his house with strip-club owners and sports dudes and sleazy businessmen. And as for Mick, he’s so secretive, he could have been dealing arms to Iran or runway modeling for all I knew.

A band’s strength is in the solidarity of its members. When they split off into different worlds, that’s usually when the problems and rifts begin that lead to a breakup. What was cool about us initially was that Vince and Tommy were kids from Covina, I was from Idaho, and Mick was from Indiana; we were all small-town dysfunctional losers who somehow became rock stars. We made our dreams into our reality. But we got so caught up in success that we forgot who we were. Vince was trying to be Hugh Hefner, Tommy thought he was Princess Diana with his high-class marriage and new friends, and I thought I was some kind of glamorous bohemian junkie like William Burroughs or Jim Carroll. I guess Mick always wanted to be Robert Johnson or Jimi Hendrix, though he was drinking so much he was beginning to look more like Meat Loaf.

Reality came crashing down on me at Tommy’s wedding. I was trying to kick, unsuccessfully, and was making an ass of myself because I had no social skills and didn’t enjoy dancing with millionaires. During the reception, I told our tour manager, Rich Fisher, that I’d been doing a little bit of heroin, as if it wasn’t obvious. And he told everyone in the management office. When I didn’t respond to Chuck’s warning letter, my management company and a counselor named Bob Timmons (who had helped Vince try to get sober) burst into my house and pulled an intervention. At first, I was pissed. But after talking for hours, they wore me down. Nicole and I agreed to check into rehab. The place was actually the same clinic on Van Nuys Boulevard where Vince had been.

Like Vince, I wasn’t ready for rehab. But unlike Vince, I didn’t have the threat of prison to keep me there. During my third day, a fat, wart-faced woman kept trying to convince me that to clean up I had to believe in a higher power. “Fuck you and fuck God!” I finally yelled at her. I stormed out of the room, and she chased after me. I wheeled around, spit in her face, and told her to fuck off again. This time she did. I went to my room, grabbed my guitar, jumped out of the second-story window, and started walking down Van Nuys Boulevard in my hospital gown. I lived five miles away: I figured I could make it.

The hospital called Bob Timmons and told him I had escaped. He hopped into his car and caught up with me on Van Nuys Boulevard.

“Nikki, get in the car,” he said as he pulled up alongside me.

“Fuck you!”

“Nikki, it’s okay. Just get in the car. We’re not mad at you.”

“Fuck you! I’m not going back to that place!”

“I won’t take you back there. I promise.”

“You know what? Fuck you! I’m never going back there. Those people are insane! They’re trying to brainwash me with God and all this shit!”

“Nikki, I’m on your side. I’ll give you a ride home, and we can find a better way for you to get clean.”

I relented and accepted the ride. We drove back to my house and threw away all the needles, spoons, and drug residue. I begged him to help me get clean on my own, without God. Then I called my grandparents for support, because whatever little sanity I possessed as an adult was due to them. But my grandmother was too ill to take the call. That night, I wrote “Dancing on Glass,” flashing back to my overdose with the line “Valentine’s in London/Found me in the trash.”

Nicole stayed in rehab for two more weeks. When she returned to the house as an outpatient afterward, something was different. We were sober. And being sober, we discovered that we didn’t really like each other that much. With the heroin gone, we had nothing in common. We broke up immediately.

To stay clean, I hired a live-in personal assistant named Jesse James, who was a six-foot-five-inch version of Keith Richards and who always wore an SS hat covering up what I believe was a hairpiece. But over time, his job metamorphosed from baby-sitter to partner in crime. He went out and fetched me drugs, and as a reward, he got to do them with me. We drank and shot up coke mostly. But every now and then I’d inject a little heroin, for old times’ sake.

With Nicole gone, I started going through girls like socks. Jesse and I would sit around and watch TV all day, I’d try to write some songs for the next album, and when that failed we’d call whatever Hollywood girl we wanted to fuck that night. But once we did all the strippers and porn stars we were interested in, we quickly became bored. We’d ride around the neighborhood and throw bricks through windows, but the fun wore off pretty quickly. I decided I needed a girlfriend. So we started picking out girls on television we wanted to go out with, imagining all kinds of funny dating scenarios. There was a cute blond local newscaster we’d watch, and I’d call her at the station during a commercial break and talk dirty to her. Then I’d watch her when she went back on the air to see if she looked aroused or flustered or upset. Though she never came over, for some reason she always took our calls.

One day, the video for Vanity 6’s “Nasty Girl” came on the air, in which the three girls in the band rubbed themselves suggestively as they sang. As a protégée of Prince’s, the band’s leader, Vanity, seemed to come from such a different world than mine. “It would kind of be cool to fuck her,” I told Jesse.

“Go for it, cowboy,” he told me.

I called our management office and told them I wanted to meet Vanity. They called her managers, and within a week I was on my way to her apartment in Beverly Hills for our first date. The second she opened the door, she fixed me with a crazy stare. Her eyes seemed like they were about to whirl out of her skull, and I knew before she even spoke a word that she was completely psychotic. But then again, so was I. She invited me into her apartment, which was only a few rooms cluttered with trash and clothes and artwork. Her house was full of weird posterboards with magazine clippings, egg cartons, and dead leaves glued to them. She called these things her artwork, and each one had a story.

“This one I call

The Reedemer

,” she said, pointing out one messy collage. “It depicts the prophecy of the angel descending on the city, for he will come to redeem the souls trapped in the bulbs of streetlamps and the little piggies will walk down the street and the children will laugh.”

That night, we never left the apartment. After all the girls I had corrupted, it was time for one to corrupt me. The artwork, she eventually admitted, was something she did after staying up for days freebasing cocaine.

“Freebasing?” I asked. “I’ve never really done that the right way before.”

And so I fell right into the spider’s web. Stuck on freebase, I lost what little remained of the self-control I had been practicing since rehab and became a completely dysfunctional paranoid. One afternoon, there were some people hanging out in my living room, and Vanity and I were holed up in the bedroom. We turned on the radio, which was attached to speakers throughout the house, and listened to music while we lit up some freebase. As we were smoking, the music stopped and a talk radio program began. I pulled out my .357 Magnum and took another hit. As I was holding the freebase in my lungs, I yelled at the radio, “You motherfuckers, I’ll fucking shoot you. Get the fuck out of here.” I think I somehow thought that the voices coming from the radio were actually the people in my living room, which was on the other side of the door. The voices didn’t stop when I yelled at them, of course, so as I exhaled a sweet puff of white smoke into the air, I unloaded my .357 through the door.

But the voices continued. “I’ll fucking kill you, I’ll fucking kill you!” I yelled at them. I kicked open the door, and saw that they were coming from a four-foot-tall speaker in the corner. I loaded another clip into the gun and littered the speaker with .357 hollow-point Magnum shells. It fell on its side. But the voices continued: “Hi, this is KLOS, and you’re talking to Doug…”

I fucking flipped out, and everybody cleared out of my living room while I tore the poor speaker apart until, eventually, the voices stopped. I think Vanity must have, in a moment of lucidity, figured out how to turn off the radio.

Our relationship was one of the strangest, most self-destructive ones I’ve ever had. We would binge together for a week, and then not see each other for three weeks. Or, while smoking crack, she would lecture me about how drinking Coca-Cola was bad for my stomach lining. One afternoon when I was at her house, a dozen roses from Prince arrived with a note saying: “Drop him. Take me back.” At the time, I fell for it, but now I think she was just manipulating me. Prince probably never sent her any flowers.

Other times, I’d be at her apartment, and she’d send me out for orange juice. When I returned, the security guard wouldn’t let me back in.

“But I was just here,” I’d say, completely confused.

“Sorry, sir, direct orders. You can’t come in.”

“What the…”

“If I were you, I would just split anyway. I don’t know what all goes on in that apartment, but I don’t ever want to know.”

One of her neighbors eventually told me that she’d have a dealer waiting around the corner, who would bring her bricks of coke to cook up as soon as I left. She’d hide it from me not because she was embarrassed about the extent of her habit, but because she was worried I’d smoke it all.

One night, Vanity asked me to marry her. I said yes just because I was fucked up, the idea was surreal, and it was easier than saying no. The relationship was just about drugs and entertainment, not love or sex or even friendship. But when she was fucked up in an interview, she told the press we were engaged. She always found a way to make my life as difficult as possible. Tommy was in his multimillion-dollar Hollywood home, and here I was stuck in rock city. No wonder it always felt like he was looking down on us—because we deserved it.

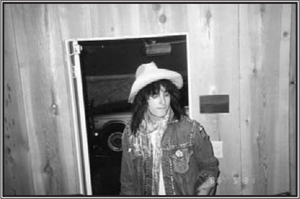

While I was dating Vanity, our managers started trying to put the band back into communication to record an album. By that time, I was not only freebasing, I was strung out on heroin again. I wore cowboy boots on the outside of tight pants, and the sides of the boots were constantly stuffed full of syringes and lumps of tar. I didn’t want to be shooting up anymore, and I put a lot of effort into trying to get straight. But I couldn’t help it. When I decided to go on methadone to withdraw, it only made matters worse and soon I was hooked on both heroin and methadone. Every morning, before I went to the studio, I’d drive to the methadone clinic in my brand-new Corvette and stand in line with all the other junkies to get my fix. Then I’d drive to the studio and spend half of each day taking bathroom breaks. Sometimes Vanity would stop by and embarrass me by lecturing the band on the dangers of carbonated beverages and burning incense that smelled like horseshit.

Lita Ford was working on a record in the studio next door, and when she saw me, she couldn’t believe how I’d deteriorated. “You used to be ready to take on the world,” she told me, “but now you look as if you let the world take you down.”

And though I couldn’t seem to write a song for the Mötley record, I managed to write a song with her for her album, appropriately titled “Falling In and Out of Love.”

As we were getting nowhere slowly on our record, my grandfather and aunt Sharon kept calling. My grandmother was getting sicker, and they wanted me to come visit her. But I was so smacked out, I kept ignoring the calls—until it was too late. My grandfather called crying one afternoon and gave me directions to her funeral, which was to take place the following Saturday. I promised him that I would be there. When Saturday rolled around, I had been awake for two days straight. I shot up some coke to give me enough energy to put one foot in front of the other, crawled off the sofa, started to dress, and fumbled around trying to find the directions for an hour. Then I changed my clothes three times, and puttered around looking for car keys and worrying about how I’d find the funeral home before I decided that it was too complicated and I just couldn’t get my act together. I sat back down on my couch, cooked up some freebase, and turned on the TV.

I sat there, knowing that as I watched

Gilligan’s Island

, the rest of my family was at her funeral, and the guilt started to seep in. She was the woman who had put up with me when my mom couldn’t, the woman who had dragged me across the country from Texas to Idaho like I was her own son. Without her willingness to take me in every time, whether she was living in a gas station or a hog farm, I probably never would have been sitting in a giant rock-star house shooting up. I’d be doing it in under a bridge in Seattle.