The Dirt (26 page)

Authors: Tommy Lee

W

hen I came home after the

Shout

tour, I didn’t know what to do with myself. We had been on the road for thirteen months, and in that time I had lost my girlfriend, our home, and most of my friends. I was sleeping on a shitty mattress and eating out of a Styrofoam ice chest. I felt lonely, depressed, and crazy. This wasn’t how rock stars were supposed to live.

So Robbin Crosby, a photographer named Neil Zlozower, and I decided to go to Martinique. It was a surreal trip because I had been on another drug binge and was too incapacitated to do anything for myself. Someone took me to the airport and put me on a plane to Miami, then someone put me on another plane, then someone moved me through customs, and the next thing I knew I was in a pool bar on a beautiful island with topless women everywhere. It was the closest thing I’d seen to paradise in my lifetime.

After a week of partying in Martinique, we flew into Miami. As I walked off the plane, a tall man in a blue blazer came running up to me. “Nikki, Nikki,” he yelled. “Your singer is dead.”

“What?!” I asked.

“Vince died in a car crash.”

My knees went weak, I grew dizzy, and I collapsed into a chair. This wasn’t part of the plan, this wasn’t supposed to happen. What was going on? I hadn’t read any papers, watched TV, or talked to anyone while I was away. I walked to a pay phone and called management.

“There’s been an accident,” Doc said.

“Oh my God, so it’s true!”

“Yeah,” he said. “Vince is pretty fucked.”

“I’ll say he is. He’s dead, dude.”

“What are you talking about?” Doc asked. Then he told me the story: Razzle was dead, Vince was in rehab, and everyone was depressed, confused, and upset.

I took the next plane to Los Angeles and went to the shitshack I shared with Robbin. I called Michael Monroe and Andy McCoy from Hanoi Rocks, and we all disappeared into a strange, intense friendship bonded in death, drugs, and self-destruction. Michael would sit around all day, combing his hair, putting his makeup on, taking his makeup off, and then putting it on again.

“You may really be a transvestite,” I told him one day after I went to look for him in the bathroom at the Rainbow, only to discover that he was using the ladies’ room.

“No, man,” he answered as he smeared foundation on his face. “I just like the way I look.”

“But that doesn’t mean you have to use the ladies’ room.”

“I always use the girls’ bathroom,” he told me, “because whenever I use the guys’ room, I get into a fight because someone calls me a fag for putting makeup on in the mirror.”

I had disapproved of shooting cocaine since the days when Vince was hanging with Lovey and showing up at concerts in a bathrobe. But with the guys from Hanoi Rocks, I started combining it with my heroin all the time. I didn’t even call Mick or Vince. I didn’t know what to do with myself: I had fulfilled a lot of my dreams with

Shout at the Devil

. It was the orgy of success, girls, and drugs I had always wanted. But, now, I was confronted with a new problem: What do you do after the orgy?

The only thing I could think to do after the orgy was to have another one, a bigger one, so that I didn’t have to deal with the consequences of the last one. Vince was on the news every day, and I was so junked out I’d ask, “Why is Vince on the news?” And someone would say, “That’s for the manslaughter charge.” And I’d just say, “Oh yeah,” and shoot up again.

Vince was my bandmate, my best friend, my brother. We had just finished the most successful tour that a young band could possibly have had that early in its career; we had experienced some of the best times together; we had shared everything, from my girlfriend to Tommy’s wife to the room-service groupies. And I didn’t call him, I didn’t visit him, I didn’t support him in any way whatsoever. I was, as usual, only interested in indulging myself. Why wasn’t I there for him? What was the reason? Were the drugs that powerful? When I thought about Vince, it wasn’t with pity; it was with anger, as if he was the bad guy and the rest of the band members were innocent victims of his wrongdoing. But we all did drugs and drove drunk. It could have happened to any of us.

But it didn’t. It happened to Vince. And he was sitting in rehab contemplating his life and his future while all I could do was sit at home and contemplate the next hit of cocaine to send up my veins. Tommy was out partying at the Rainbow with Bobby Blotzer of Ratt, Mick was probably sitting on his front steps nursing a black eye, and Mötley Crüe was dead at the starting gate.

I

was sure I was dead. I woke up on the beach, and the sky and sea were pitch-black. There was a glow of light coming from the distance, and I walked toward it. It was the glass windows of Vince’s house. I looked inside to see Beth, Tommy, Andy, and some of the other guys in the living room. But they weren’t partying. They were sitting in silence, looking sad, like something terrible had happened. When they spoke, they seemed to be whispering. There were tears in Beth and Tommy’s eyes. I figured that they were crying for me: that I had drowned in the water and they had discovered my body. Now I was just a soul or a ghost or some sort of spirit, stuck on earth in limbo to do penance for my life or for my suicide. But where was The Thing? Why wasn’t she there crying with them? After all, it had been to get her attention that I waded into the water in the first place. Maybe she was with my body at the morgue.

Since I was a ghost, material objects could no longer stand in my way. So I tried to walk through the glass window into the room in order to hear what Tommy and Beth were saying about me. That was when I really hurt myself. The noise of my body colliding into the window shocked the group in the house to life. They ran to the window and looked out in panic, only to find me lying on my back in the sand.

“Where have you been, dude?” Tommy exclaimed when he saw me.

I guess I was alive after all.

When they told me about the accident, Beth said that a lot of people thought that I was in the car: Razzle had been disfigured so badly that he looked like me. It wouldn’t have made a difference, because it was over for Mötley Crüe, as far as I was concerned. I was pretty used to being a hobo, and I could always go back to bumming and crashing on couches.

When I came home, I was shaken. I just thought, “Alcohol sucks,” and then I started drinking more heavily than I ever had. The Thing soon left the house. I bought a BMW 320i; and one night I was home talking with the drummer from White Horse about how fucked up my relationship was. He wanted to see the BMW, so I opened the curtains to show him, and the car was gone. I called the cops and told them that my girlfriend had stolen my car. They could tell I was drunk, and didn’t seem to really care. “Okay,” they told me. “We’ll go out and look for her. And if we see her with the car, we’ll shoot her, okay?”

“Never mind,” I said.

“She’ll be back, don’t worry about it,” the cop said as he hung up.

But she never did come back. I’ve always been faithful to whoever I’m dating, because if you cheat on your wife or girlfriend, you start to believe that she is doing the same thing to you and it breeds fear and distrust and eventually destroys your relationship. But the women I’ve dated and married haven’t always felt the same way: they can go fuck whoever they want and then come home and say, “Hey, baby, what’s going on?” I don’t understand how someone can do that to a person they’re supposedly in love with, so if they do that to me, I have to assume they’re not in love with me. And that’s what happened with The Thing. I found my car outside the house of a professional boxer. When I confronted her, she said, “Fuck you. I’m with him. He’s much younger.” Though she never said it, I felt that she thought he was a better bet than me, that he would make more money. I always told her that in a few years I would have multimillions.

“Good luck in your poverty,” I told her cockily, though inside I was as confused as a whore in church. I went home, paid the last month of rent, and told the management that I was moving out and that The Thing was responsible for the house now.

I felt ancient, exhausted, and useless: too old ever to get another young, good-looking girlfriend and too old ever to find another band on its way up like Mötley Crüe had been. So much for young women, multimillions, and arena rock. I could travel the country, playing in the streets for money like Robert Johnson—I just had to change my way of thinking. So I moved into an apartment in Marina del Rey and began brainwashing myself with alcohol. Each night before I went to bed, I could feel myself growing more bloated, like a sweaty, disgusting pig. And not once did I think about visiting Vince in rehab. I wasn’t angry with him, but I was upset. Even though I knew it wasn’t his fault, I couldn’t bring myself to forgive him either.

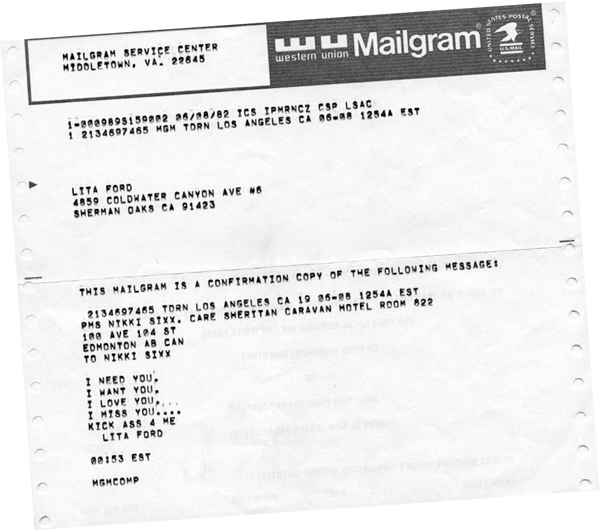

fig. 3