The Dirt (54 page)

Authors: Tommy Lee

As soon as I walked in, the doctors looked at the anger still seething on my face and then down at the blood coagulating on my hand and didn’t have to ask what had happened. They brought me into the X-ray room and informed me that I had broken my hand. They bandaged it and said there would be no charge. They knew what I was going through because they had seen it so many times before, though perhaps not to this exact degree of self-destructiveness.

More and more, I fell asleep at Skylar’s bedside crying and confused, frustrated that this cancer beyond my control was growing and consuming my daughter, my life, and our future together. Every time I returned to the hospital, Skylar was in more pain and confusion. We would watch

Married… With Children

in the hospital. Just a month ago, she used to drop whatever she was doing and dance around the house to the theme song, Frank Sinatra’s “Love and Marriage.” But now she just stared listlessly at the television, knocked out on morphine. If we were lucky, a smile would crack open across her face and send our hearts racing with happiness.

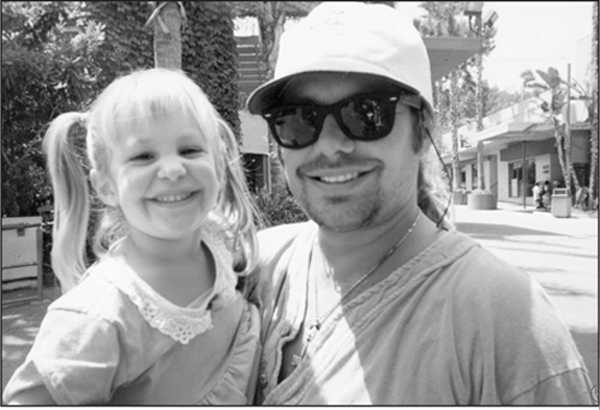

With the tumor on Skylar’s right kidney starting to press against her lungs, it was a losing battle trying to preserve that smile. I brought Skylar her favorite toys and the clothes she liked to dance in. We watched Disney videos and sang children’s songs together. Since I was now signed to Warner Bros. Records, I used my connections to bring entertainers in Bugs Bunny and Sylvester costumes to the hospital with big gift baskets for Skylar and the other children in the ward. On Easter, Heidi and I went to Sav-On and bought bags full of candy and Easter egg painting kits. Then I did something I never would have done for Mötley Crüe no matter how much they pleaded: I stripped out of my clothes and put on a giant, fuzzy Easter Bunny outfit.

Skylar didn’t even recognize me until I started talking, then she burst out laughing. I cried, and as the tears mingled with sweat under the outfit, I turned around and said, “Sharise, hand me those eggs.”

“What did you just call me?” came the curt, sharp, and angry voice of Heidi. Sharise wasn’t even in the hospital, and if there’s anything a girlfriend doesn’t forgive, it’s calling her by an ex’s name, even if it occurs at the sickbed of a child. For the next few minutes, Easter turned into Halloween as we put on a very different kind of show for the kids. For a relatively young girl in a new relationship, Heidi was under a lot of pressure she had never bargained for between the fact that I was still technically married and that all our dates were taking place in the presence of nurses and Sharise instead of waiters and friends. At first, everyone just saw her as a blond bimbo. But after months of Heidi hiring entertainers such as a Snow White impersonator, sitting at Skylar’s bedside, holding her hand every day, and being very careful not to compete or interfere with Sharise, the doctors and Sharise’s family eventually accepted her, though never quite enough to treat her like part of the family.

“Daddy,” Skylar asked when she woke up one morning, “I’m never going home, am I?”

“Of course you’re going home,” I said. And I wasn’t lying. The doctors had told me that we could take Skylar home and simply bring her in for chemotherapy. After a month straight in a hospital cot, Skylar finally returned to her own bedroom. Unfortunately, she didn’t get to enjoy it for long. Every night, she would sleep less and cry more, saying that her stomach hurt. When she went to the bathroom, she’d scream with a pain that sounded more wrenching than anything I’d experienced in a life eight times as long as hers.

We brought Skylar back to the hospital after only four nights at home. The doctors said that scar tissue from her last surgery had formed on her intestines, twisting them and obstructing her bowels. When Sharise told our daughter that she was going to have to endure another operation, Skylar said in the weakest, saddest, most innocent voice I’d ever heard: “Mommy, I don’t want to die.” She knew that what was happening to her was not normal, that all the smiles and jokes coming from Sharise and me were forced, that the relatives and friends who visited never used to cry when they saw her.

“The nice doctors are going to help you go to sleep for a little bit, while they do another operation,” Sharise said, dabbing the sweat off Skylar’s forehead. “And when you wake up, Mommy and Daddy will be right here waiting for you. We love you, honey. And everything is going to be okay. We’ll all be home again soon.” I needed to believe that what Sharise was saying was true as badly as Skylar did.

After the operation, Skylar looked even worse than before. I noticed for the first time how all the life had drained out of her face, how forced and short her breathing had become, how every ounce of baby fat had been replaced by bones pressing against skin. “Daddy,” she begged. “Please don’t let them cut me again.”

I didn’t know what to say: the doctors had already told me that her right kidney would have to be removed. Three days later, she was in the operating room again. And when the doctors wheeled her back, it wasn’t like the TV shows. They never said: “Congratulations, the operation was a success.” They said, “I’m sorry, Vince. But something unexpected happened. The cancer has spread to her liver, intestines, and dorsal muscles.”

“Did you remove the kidney?”

“No. We couldn’t even remove the tumor. It isn’t responding well to chemo. It has bonded so tightly to her kidney that to remove it would cause fatal blood loss. That, however, does not mean that there is no hope. There are other options available to us and, God willing, one of them will get rid of this thing for good.”

But “this thing” kept growing, consuming the girl I loved too much too late. On June 3, I received a call from the oncologist in charge of Skylar’s doctors. When you’re at the hospital every day, the last thing you want to do is pick up the phone at home and hear a doctor’s voice, because it can only mean one thing. Skylar had stopped breathing, the oncologist told me. The doctors had just placed her on a respirator and injected her with a medication that, in effect, paralyzed her so that she wouldn’t expend excess energy. She couldn’t laugh, she couldn’t move, she couldn’t speak. In four months, she had gone from a happy little four-year-old to a sad, wired-up mannequin. She never even had a chance to live, and now she was in a worse condition than most people in nursing homes. For all practical purposes, she was death with a heartbeat, though I tried to convince myself that it was just a temporary sleep.

She was a strong girl, though, and her body continued to fight the cancer. Her signs stabilized, her heart rate increased, and every now and then her lungs would pump a little air on their own. After a month and a half of this limbo state, the doctors decided that they had no choice. It was better to attempt to remove the tumor than just leave her hovering in and out of life. The operation was extremely dangerous, but if Skylar made it through, they said, it was very likely that she would recover.

Sharise’s family, my family, Sharise, and my son Neil joined Heidi and me in the hospital and we all sat nervously together, taking turns running out for food, while waiting for a word from the doctors operating on her. We fidgeted the whole time, unable to utter a sentence without bursting into tears. I thought about how cancer ran in my mother’s side of the family, and wondered if this was my fault. Or maybe I shouldn’t have let the doctors treat Skylar with chemotherapy in the first place. I should have told them to remove the kidney. I should have brought Skylar to the hospital when she complained of a stomachache half a year ago. Various thoughts ran through my mind, all containing those poisonous and impotent two words,

should have

.

Finally, after eight hours of anxiety, the doctors came out to say that Skylar was back in her room. They had successfully removed the tumor: it weighed six and a half pounds. That’s how much Skylar had weighed when she was born. I couldn’t even conceive of something that immense growing inside her.

I wanted to see what was killing my daughter, so I asked the doctors if they had kept the tumor. They brought me down to the pathology lab, showed it to me, and my stomach turned. I had never seen anything like it before: It was the face of evil. It lay spread out in a metal pan, a nacreous mess of shit. It looked like a gelatinous football that had been rolled through the depths of hell, collecting vomit, bile, and every other dropping of the damned that lay in its path. It was, in every conceivable way, the exact opposite of the daughter Sharise and I had raised.

In the process of removing the cancer, the doctors also had to take out Skylar’s right kidney, half her liver, some of her diaphragm, and a muscle in her back. How many more organs could a girl lose and still be alive? But she was breathing and the cancer was gone. Every day she recovered a little more, until she could speak and smile. Every gesture she made—a blink, a yawn, the word

daddy

—felt like a gift. I thought that everything would be okay now, that the nightmare was over, that Skylar could be a child again. I stopped drinking at Moonshadows and began cleaning up the house and my life for Skylar’s return.

Six days after the operation, I was walking into the hospital with a giant stuffed panda when I was greeted by the doctors. They had that look, the look that says everything and nothing at all, the look of bad news that must inevitably and regrettably be delivered. I braced myself, and knew before a word was spoken that I’d be back at Moonshadows that night.

“Vince,” the oncologist said. “It seems like an infection may be developing around Skylar’s left kidney.”

“That’s all she’s got left. What does this mean?”

“I’m afraid it means we’re going to have to operate again and clean up around the kidney.”

“Jesus. You’ve already operated on my baby five times. How much more can she take?”

It turned out that she couldn’t take much more. After the operation, she went into a fast decline: her lungs, her left kidney, and her liver all began a mutiny, refusing to function properly. Mercifully, she soon slipped into a coma. Her little body just couldn’t take any more. It had been cut open and sewn back up so many times; it had been pumped so full of drugs; it had been shot through with more radiation than anyone should be exposed to; it had endured the slicing, dicing, rearranging, scraping, and removal of so many of its contents that, like a brake that has been pressed over and over, the parts had worn away and no longer knew how to work together. When your body starts to fall apart, there’s no one who can fix the machine. They can only keep it running for a little while longer. And sometimes I wonder whether I did the right thing by keeping Skylar running for so long, keeping her in such pain for five months—one-tenth of her entire life.

I began to drink so heavily that I wouldn’t last more than an hour at Moonshadows without passing out or vomiting all over Kelsey Grammer. I cut the most pathetic figure: a father who just couldn’t deal with the pain of knowing that soon he would have to undergo the worst tragedy that a parent can bear—having to bury his own daughter. I had given Skylar everything I had to give—even my own blood for transfusions. I would have been willing to lay down my own life if it would have helped. I had never thought anything like that before—not about my wives, not about my parents, not about anybody. Perhaps that was why I was trying to kill myself with drink, so that somehow I could martyr myself and exchange my suffering for hers. Every morning, I would sit at her bedside hungover and read her stories and tell her jokes and pretend to be brave, like everything could still possibly be okay.

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise when the oncologist told me to start bringing in her relatives and friends to say their good-byes. But that was the first time I had heard the doctors say that there was no hope. Before, there was always a small chance or a good chance or a tiny chance or a fair chance. But never no chance. Perhaps I had reassured Skylar so many times that she would return home one day and we’d build sand castles on the beach again that I began to believe it myself. I walked into Skylar’s room with Heidi afterward and saw drops of blood on her lip. Heidi was outraged that the nurses would just leave her lying there in that condition. She took a tissue out of her purse and bent down to wipe it. But the blood just stayed there on Skylar’s lip. It had coagulated. Heidi kept wiping it and crying, “You fix it, you fix it.” We both broke down on the spot.

We stayed with Skylar until late at night when we left to get some food at Moonshadows. In the meantime, Sharise and her parents arrived to sit with Skylar. As soon as we settled down at a table, the bartender said I had a phone call. “Vince, get to the hospital now,” came Sharise’s trembling voice on the other end. “Her vital signs are dropping. Fast.” I didn’t panic, I didn’t cry, I just hurried.

But I was too late. By the time I arrived at the hospital, Skylar had passed away. And I never had a chance to say good-bye and tell her one more time how much I loved her.

SHARISE SAID THAT SKYLAR had passed away peacefully. When her heartbeat started slowing, her eyes had opened with a momentary flash of fear and met her mother’s in search of an answer or explanation. “Don’t be scared, sweetie,” Sharise had reassured her, squeezing her hand. “Go to sleep now. It’s all right.” And so Skylar slept. In the meantime, I sat in traffic on the Pacific Coast Highway and, for an instant, my heart jumped in my chest. But I was in such a hurry to be by Skylar’s bedside that I ignored it and didn’t think about it. But afterward I realized that when the woman that I loved most in this world left, my heart knew it and, for a moment, wanted to catch up with her and join her.